BY OLUWASEUN ABIMBOLA

Bright smiles. Warm hugs. Quiet postures. Uncertain stares.

These were my initial impressions of students I met seated at the conference table in the Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CCAMH), SUCCEED Research office. They were waiting for other students who were participating in the documentary shoot of the Excelsior Class of 2023.

I was struck by a young man’s frame and almost fluffy looking, but thick mane of hair. He reminded me of Samsong, the Gospel singer. He had a quiet smile that characterized the innocence in the room. I was drawn to him. So, I reached out to warmly greet him. “Hello,” I said, “My name is ‘Seun.” “I am Ehis”, he replied unassumingly. Our exchange was brief and the subdued air in the room soon turned to boisterous laughter and bants. The other students were arriving now, and the mood in the room had changed. Soon, we were on our way out. Little did I know that my encounter with Ehis and his classmates would reveal a group of remarkable individuals whose journey I would soon become deeply invested in.

Advertisement

But my interest all started with Oluwatunmise.

“As Martin Luther King once said, “If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as a Michaelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, ‘Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.’”

Those were Oluwatunmise’s opening lines during the shoot. It was a familiar quote, but she said it with so much poise and elegance that the desired effect wasn’t lost on us. It left us all spellbound; so captivating that it brought those words to life. It felt like she embodied the essence and excellence of the class, setting the stage for others that followed. Her graceful delivery was like another classmate’s – Tijani, a short, sturdy young man – whose repeated ‘that-is-a-fact’ line made his speech the most unforgettable for the day. As an on-set dialogue coach, all the students had run their scripts by me for necessary editing and corrections, but I had nothing to say about Tijani’s script. To be fair, maybe nothing for anyone. But Tijani’s speech was so well-delivered I almost sucked him into a tight embrace.

Advertisement

Fatihat’s calmness and brilliance were as much a shining light as Azohitare’s graceful reminder of the social excellence of their class. I also remember the visible lines of worry and vulnerability on Anthony and Oghogho’s faces. They looked human. The denouement was when Oghogho paid her respect to a member of the class, Segun, who died two years ago, capturing the grief and sadness of the class in such a bated but powerful speech. However, my admiration for this class wasn’t just about these isolated impressions, it was about the representations. This wasn’t just a class putting their best faces forward to speak about their times, they were simply the best out of many other bests.

As we walked through designated shooting sites, I spoke with everyone on set. It was a quick, informal one to reflect on their times at the College, their views on lecturer-student relationships, the uniqueness of their class, and most importantly, to me, their experiences with the Provost, Professor Olayinka Omigbodun FAS. When I struck up a casual conversation with these bright-eyed students, I couldn’t help my excitement to learn more about this MBBS graduating class. Their words reflected the collective spirit of the class, a spirit that exuded an unbridled passion for medicine and a thirst for knowledge that was palpable.

Intellectual brilliance and quick thinking were also hallmarks of this class. Yet, their excellence extended beyond the confines of the lecture halls and hospitals. They excelled in debates, quizzes, sports, and a myriad of social activities. Anthony and Azohitare had captured this in their speeches. Their achievements were a testament to their versatility and well-roundedness, qualities that would undoubtedly enrich their medical careers and lives beyond.

However, what struck me most was their strong sense of community. The close-knit bonds and camaraderie – to borrow Azohitare’s word – among these students were truly remarkable. I began to imagine what it must have been like – organizing study groups, supporting each other through the rigours of medical school, or simply sharing a meal together – I could feel their togetherness. It’s evident that this sense of community would be an asset as they embarked on their medical careers, where collaboration and support are often the pillars of success.

Advertisement

About Excellence, Versatility, and Being More…

I learned a lot about quite a few students too; about:

Hillary Alemenzohu MBBS, who successfully passed both steps of the United States Medical Licensing Examinations, active member of the debate team, reached the Jaw War finals, and participated in health education outreach programmes.

Paul Olapade, MBBS, who interned at a cancer tech startup (Oncopadi) and contributed to the development of a virtual consultation platform (Project ARC), co-published in The Green Journal (Journal of the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology).

Advertisement

Bukola Oduntan, BDS, who led an outreach team providing free refreshments to over 800 UI students, served as a panelist in an academic seminar on time management and study techniques.

Fatokun Toluwanimi, BDS, co-founder of The Holistique Drive Initiative, Millennium Fellow, Class of 2022 and conducted a health insurance-based outreach (Project Hinsure).

Advertisement

Anthony Chinonso UGAH, MBBS, who held multiple leadership positions and was a member of various organizations, organized successful webinars and quiz competitions, and was actively involved in community health awareness programmes.

Adeoye Davids, MBBS; led the 2k18 Football Team to multiple victories and received awards (2k18 meaning that they crossed over to clinical school in 2018).

Advertisement

Rockson Godwin Oyefolahan, MBBS, who held various leadership positions, achieved success in sports, including football and athletics.

Julianah Adebisi, BDS, a Fellow, United Nations Academic Impact and Millennium Campus Network, Co-founder and Executive Director of The Holistique Drive, and an active member in various organizations.

Advertisement

Oluwademilade Afolabi, BDS, a Global Goals Action Ambassador, who was first place in a global goals resolution presentation, and Founder of Heritage Web Dev, an organization that builds and develops websites.

Salami Oluwaferanmi David, MBBS, who held numerous leadership roles and organized events, a speaker at the UCH Students Representative Council, who made significant contributions to healthcare and community initiatives.

Promise Chimuanya Ugochukwu, MBBS who had a first class in Human Nutrition from the University of Ibadan. Did an internship at the University College Hospital, and got a scholarship for her Master, but chose Medicine. She was also into community work – like Red Cross, Hamstrings, etc., and won sports medals. She equally won the Wells Scholarship.

Ifeyinwa Oluchi Ogbogu, MBBS, who served as the Headquarters’ Administrator of FAMSA, represented FAMSA at the WHO Regional Committee for Africa and was recognized as a 2022 Doha Debates Ambassador.

Daniel Ehis Aigbonoga, MBBS, yeah, the same Ehis, a Winner of the 2021 Bayer Fellowship grant, who took second place in the 2021 National AMSUL Scientific Conference and had full funding to present at the World Congress on Undergraduate Research.

Raheem Olamide, MBBS, Founder of RAHOLA007 Enterprises, that produces high-quality laboratory coats, ward coats, and scrubs.

Efosa Iyawe, David Babalola, Olawunmi Fisayo, and Olamide Egbeyemi, core members of the UIMSA Royal Quiz Club, who won most of their inter-MSA competitions at regional and national levels.

Jaachimma Nwagbara, the first female President of The University of Ibadan Medical Students’ Association (UIMSA) since its inception in 1960.

Jesujuwon Olawuyi and Fatihat Sanusi, both brilliant public speakers who led both the Faculty of Clinical Sciences and the Alexander Brown Hall to the finals of Jaw War, the largest public speaking competition in Nigeria.

As I wrapped my thoughts around this extraordinary class, I was filled with optimism about their journey ahead. Wouldn’t it be a blessing for them to carry forward the qualities that define them—fearlessness in voicing their opinions, intellectual brilliance, versatility, and a strong sense of community? I have no doubt that they will excel and make a profound, positive impact in the field of medicine and beyond. It was clear that this class had a remarkable ability to advocate change and progress, a trait that would undoubtedly serve them well in life.

So, I sent a message to the Provost: “Hello Ma… I think I can do a solid story about the class.”

So here I am, attempting that solid story. A short one. For now.

About Leadership and Service…

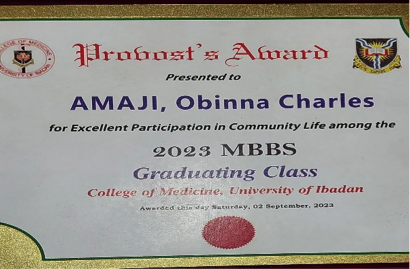

Full name: Obinna Charles Amaji.

When I met Obinna at the documentary shoot, I knew there was something different about him. He had introduced himself as the Class Governor.

I was observing him already. His coordination of the class members, and calm discussions of everybody’s responsibility on set. Obinna reminds me that a true leader goes beyond healing the body; they touch the hearts and souls of those they serve.

He was simply a leader.

It came as no surprise when I learned that he had been honoured with the prestigious Provost Award for Excellent Participation in Community Life.

Enter Semiloore too.

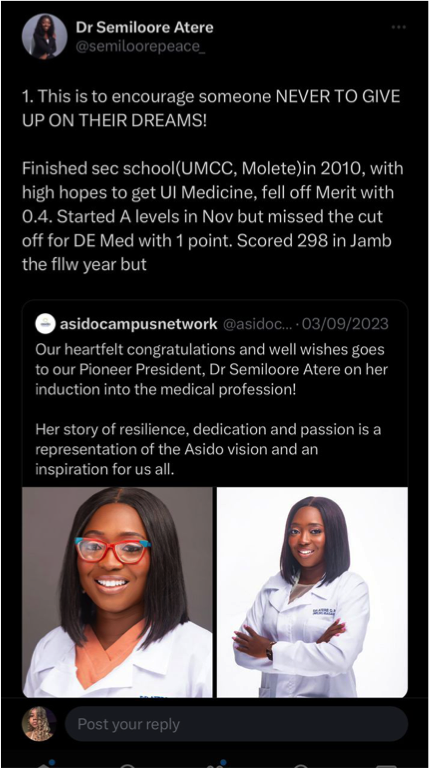

Talking to Semiloore was an easy decision after reading her story on Twitter.

Her journey wasn’t solely about personal success; it was about lifting others up. Her story was not just about becoming a doctor; I felt it captured the power of resilience, determination, and the profound impact one can have on others when they refuse to give up on their dreams. She became the face for about 12 other people in the class who came back to study Medicine after their first degree.

But more than the spotlight on her achievement, Semiloore took pride in helping fellow students reach their potential despite their challenges. I was tickled. So, I called her in the middle of a very busy morning.

I learnt a lot about her that I hope to explore some other day.

She started a mental health club, the first of its kind in Sub-Saharan Africa, to support students. She became the pioneer president of the student arm of Asido Foundation, that is the Asido Campus Network. The Asido Foundation is a non-profit that advocates for better mental health for people. But what really ignited her passion for mental health was a tough moment when a classmate tried to end their own life. Semiloore’s quick thinking and kindness saved that person. She was literally a hero.

About Mobility, Peculiarities, and Uncertainties…

When I reunited with Azohitare, Oluwatunmise, and Oghogho, there was an unspoken elephant in the room. This time, we were joined by a new face, Bolu, whom I hadn’t seen during the documentary shoot. I was charmed by his informality and openness. The elephant in the room was the “japa wave” – that overwhelming desire among many young Nigerians to leave the country. It struck me as a contradiction that a class so exceptional was so certain about leaving the country.

“Are you planning to leave the country?” I finally asked, breaking the silence.

“Aren’t you?” they retorted almost in unison.

It was clear that they were all contemplating an exit. Their plans to leave were not just individual choices. They mentioned how training in Nigeria could destabilize or hold you down, unplanned impacts like a strike, or the example of a doctor, whose training for two years to be a consultant was cancelled because they didn’t train under a certified consultant.

However, the kindest response to their exit plan was the plan to return to give back after training abroad. They acknowledged that family ties in Nigeria, the probability of loneliness abroad, and the unsettling experiences of training in Nigeria all played into their considerations. But they also need to make good money.

“Why is money so important to you guys?” I asked.

“You need money to live, to be comfortable,” they said. I know. It’s a fact. “More so,” they told me, “Doctors in Nigeria are on their own if they suffer any accident in the line of work.”

“What about hazard allowance?”

“What? The N15,000?” One of them responded, expressing the stark reality of the situation.

I said to them. “But you have had a highly subsidized education. You’ve paid so little to get so much, how can you want so much from a system you haven’t really put so much into yourself?” Oluwatunmise countered, “Education is cheap for every course in Nigeria, not just for doctors. If an engineer can work 9-5 and earn a lot of money, why should I, as a doctor, spend almost 24 hours in the hospital and earn less?”

While I suspected there might have been some exaggeration in their words, I understood the frustration and disillusionment they were expressing. The conversation echoed the grim reality of the brain drain being experienced in Nigeria, with the country at risk of losing another set of brilliant students if no significant changes are made soon.

However, amidst the uncertainty about the future, there were still fond memories of their time at the College of Medicine. “Personally, I would like to experience Medicine again, as much as I didn’t enjoy the procedures at times,” Azohitare shared. “I don’t like stress, and it wasn’t easy being far from home, …When we left for UCH, disconnecting from the UI community and our friends in the university hit me hard. But I still wouldn’t trade my training for anything.”

They recounted the rigours of their training, from the relatively manageable pre-clinical experience to the challenging transition from basic science in the second and third years. “The number of signatures we had to chase was overwhelming. I didn’t like the deadlines. I felt like all that stress didn’t necessarily contribute to our training,” Azohitare recalled with faint exhaustion.

“I think my experience had a significant impact on my mental health too,” Oghogho added. “Mentally, I was exhausted and didn’t feel like doing anything anymore. I was terrified during my final exams. My mother called me every day. I was so relieved when I passed.” It made me briefly wonder if students took advantage of the counselling services offered at the College of Medicine.

Bolu’s experience was a tad different. His carefree view of his medical journey tickled my curiosity. “It was very easy,” he said. “I was never serious, I was just vibing. I was clinging to those who appeared serious, and I managed to avoid failing for 6-7 years.”

He said, “I kept telling myself next week, next month, I will figure this out, but still…nothing.”

It felt like something I had heard over and over. I asked Azohitare if she knew what she wanted to do post-graduation. “Honestly, I don’t know.” She sounded vulnerable. “I try not to burden my mind a lot about it,” she added.

I was sad. Momentarily. Despite dedicating six years to the pursuit of medicine, how can clarity about the path ahead remain elusive? It felt like medicine was an unending journey, a series of checkboxes to tick: complete housemanship, undergo the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC), do a residency, and so on. Yet, other factors, like the state of the country, continued to influence their choices. Many had entered medical school with a specific specialty in mind, only to see those plans dissolve before graduation, leaving them to settle for whatever opportunities came their way.

I couldn’t help but wonder if there was a solution to this uncertainty. “Do you have any mentoring programme or formalized arrangement with faculty members to guide students in finding clarity about their post-graduation paths?” I asked.

The response I received was a collective “No.” They explained that while there were mentoring matchups available, they didn’t quite align with what I was seeking. “It’s not quite as structured for post-graduation opportunities or options as you’re thinking,” they clarified. In short, nothing was specifically tailored to help students find clarity early about the specialty they want to get into.

“But do you think such a programme could provide students with the clarity they need for their future?” I pressed further.

“Perhaps,” came the tentative response, “but this issue extends beyond mentoring. Many students find themselves in a state of indecision. Even those who actively seek out relationships with lecturers may still grapple with uncertainty.”

At this point, Oluwatunmise cut in, offering her perspective. “Take me, for instance. I’m passionate about everything, but reality dictates that I can’t pursue every interest. Some individuals simply don’t know what they want, while others might not even be interested in medicine at all. For many of us, our plans are still evolving.”

“So, people really do study medicine for 6 years and say they are no longer interested?”

“Yes.”

“How? Why?” I might have faked a shock at this point. But they heartily responded.

“Some people are here because their parents said so…” Oghogho was speaking now. “Some people come in with certain ideas of medicine, but over time they realize it isn’t true… For example, some people study medicine because they think being a doctor means you will be rich, but they soon find out along the way that it isn’t true. That disappointing and painful realization can make many quit even before starting out after graduation.”

The ladies were the ones talking mostly at this point. I turned to Bolu who, by now, had struck me as a very charming and interesting character.

“Do you want to be a doctor?” I asked him.

“I want to make money,” he replied.

About Two Brothers Setting a New Record…

I spoke to the two best-graduating students from the class, Efosa Iyawe and Kelechi Ughagwu.

Their story is a unique one.

It began back at Tedder Hall in the University of Ibadan where they shared many unforgettable moments together as hall residents. They found themselves as roommates during their final year at Alexandra Brown Hall in the University College Hospital, Ibadan.

I had imagined several moments of intellectual bashes and friendly bants in my head.

In one corner of their room, they might have had stacks of textbooks and study materials, engrossed in deep discussions about complex subjects, challenging each other’s intellect, and striving for academic excellence. But in another corner, they probably shared laughter and stories, creating memories that would last a lifetime. They might have enjoyed late-night snacks, debated on various topics, or simply relaxed after a long day of classes and clinical rotations. Perhaps it was a sanctuary where friendship and learning thrived side by side, and where the bonds of brotherhood grew stronger with each passing day.

“Have you always been the best in class?” I couldn’t resist the urge to ask them when I met both independently.

For primary education, Kelechi attended Saint Louis Nursery and Primary School in Akure, Ondo State, a well-regarded Catholic mission school. While he wasn’t always the top student, he told me he consistently ranked among the top ten, and in his final year, he achieved the distinction of being the third-best student. He recalled that the margin between him and the second-best student was a mere 0.1, a memory that stuck with him, even in his young age.

Kelechi went to FUTA Staff Secondary School, where he wasn’t the best student in the beginning. But things changed when he did poorly in his GCE exams in SS 2. He told me this was when it all changed for him. It motivated him to work harder, and by SS 3, he became the top student, the valedictorian of his school, and had the best WAEC result in his class. This experience taught him to always put in extra effort to get better results in academics or even life generally.

For Efosa, it was a different ball game. He attended Adeline College in Abeokuta. Despite coming from Abeokuta, he consistently ranked as the top student throughout his primary and secondary school years. But he felt he was coming to U.I to compete with the best from across the country. So, when he entered the University of Ibadan, he did so without any special advantages. However, he accomplished an exceptional feat by obtaining a perfect CGPA of 7.0, which was the grading point at that time, alongside about ten others at the end of his 100 level (first year) in University. Something had switched in him.

“So, can you share your study patterns and how you’ve managed to excel as a student? Are there any principles or strategies you follow?” I remember asking Kelechi.

Kelechi told me that his study pattern evolved over time, and that he incorporated effective techniques learned from others. He emphasized attending lectures regularly and paying close attention to what lecturers taught. “… Many of our lecturers base their exam questions on what they’ve taught in class. So, it’s essential to attend lectures and closely follow the materials they provide. However, sometimes the lecture materials might not cover every aspect of a topic comprehensively. That’s when I turn to additional resources like textbooks, online videos, or other helpful materials.”

Efosa had his own doubts from the onset: “I felt like I wasn’t good enough for this core clinical thing.” But he soon cracked the code. He told me that there is a finesse that comes into play when it comes to clinical examinations. He said, “You could have people who could read, but when it comes to clinical exams, you are being assessed while doing it. There are the objective structured examinations, there is the long-case examination where they watch you and how you interact with patients, and then they grade you. I began to realize there is a finesse that comes to play when it comes to those kinds of exams… that the more you interact with patients, the better you become at those things.” I hear him.

I acknowledged my admiration for the efforts they put in. But I had always thought there was some ego-tripping about medical and dental students, maybe some kind of classism, that makes them feel superior to other departments in the College. I wanted to know if I was wrong.

“Well, I wouldn’t exactly label it as classism or division,” Kelechi said. “It’s a bit complex because we’re all part of the same College, right? And we interact every day. There aren’t any real barriers between us. I think the thing is that we medical students tend to be quite vocal or loud about our profession, and we’re proud of what we do. It’s this pride and outspokenness that might sometimes rub on others the wrong way. But we are cool.”

When I spoke to Efosa, I was more concerned about the distinction cap for courses. “I’ve been pondering about the issue of credit allocation in medicine, especially in relation to awarding distinctions to students. Do you think the college’s system allows for fair recognition?”

Efosa was all over it, it seemed he had been waiting for a while to speak on it. “Thank you for raising this question; it’s a topic I’ve been quite vocal about among my peers,” he said. “To address your concerns, let me start by saying that the College of Medicine indeed values excellence, and I’m pleased that they’ve started awarding prizes for excellence in different courses during induction, a change from the past… In the past, this recognition was limited to the Convocation ceremony. However, when we compare our approach to that of other schools like UNILAG or LASU, we can see a distinct difference in the way excellence is celebrated. Even if a student doesn’t excel in all courses, having a ‘Best in Class’ or ‘Distinction’ recognition in at least one area can be highly motivating….

Some argue that maintaining a high score like 80 reflects positively on our ability to teach. I’ve personally interacted with students in the College of Medicine from other institutions, and I can confidently say that U.I. students are ahead in terms of knowledge. However, the pursuit of distinction has become exceedingly challenging in clinical courses, such as Medicine and Surgery or Paediatrics. This has discouraged some students from giving their best, as the bar seems almost unattainable. When it comes to recognition, I believe it’s essential to work on our reward system. While we’ve made some progress with awards, we should strive to recognize and reward excellence across all disciplines within the college, not just during induction but throughout the academic journey. I’m glad they’ve started this trend, and I hope it continues.”

Soon, our discussions revolved around the respect culture in Medicine, the talk-down some residents suffer from consultants, the brain drain, and how things can be better.

“Sometimes, it feels like we’re stuck in a cycle, akin to a never-ending marriage with children scattered all over the land. The pressure is immense, and I’m not even talking about politics here. My belief has always been that we, as a people, should move forward. However, progress cannot be achieved by merely wishing it. We must recognize that true change must come intrinsically. The best way forward is to harness our collective knowledge and unite as one. The idea of leaving our homeland to build a life elsewhere hasn’t yielded the expected results. So now, it’s on us, on those who have left, to come back and contribute. The problem is the situation back here can be very discouraging. I know people in Lagos, Abuja, and beyond who trained in the US or the UK and then returned to establish their practices. However, the initial enthusiasm often fades when they encounter challenges.

What draws them back is the hope for conducive conditions—lower taxes, better job opportunities, and overall, a more motivating environment. Imagine if even within the government system, there was substantial remuneration, stipends, and strong motivations to work here. Personally, I have a passion for teaching. If I were in the US, for example, coming back to teach in Nigeria would require more than just goodwill. I would need a significant incentive. It’s not about comparing a few thousand dollars to millions; it’s about having the infrastructure and essentials in place. Reliable electricity, clean water, decent roads, and security are basic amenities that should never be taken for granted. If these factors were consistent, people would find it much more appealing to stay and work here. We need a system where people not only want to come back but also genuinely thrive and make a difference, rather than constantly looking for alternatives elsewhere. This is the key to progress, both for individuals and for our nation as a whole.”

As they talked about their future, I could feel the weight of their expectations and their desire to make a meaningful impact on the country’s healthcare system. They envisioned themselves as medical educators, dedicated to teaching and nurturing the next generation of doctors. Their dream is to contribute to improving healthcare in Nigeria and inspiring others to do the same. It was a unique window into the hearts of young individuals whose dreams, perhaps, represent the new voices in the medical community determined to make a difference in some of the gaps and challenges seen in the system.

I enjoyed talking to both valedictorians. I admire their reflections on the broader challenges faced by Nigeria’s medical landscape, including the need for better remuneration, infrastructure, and support to encourage talented medical professionals to stay and serve in our home country.

In their eyes, I saw hope.

About the Provost…

“I really like the Provost, her efforts towards the Students’ Hostel project and supporting indigent students are so great. Do you know how many students she literally helped to stay in school?”

“But I think the only regret is that many of us didn’t get to know her personally. She seems like a really lovely person.”

That was the summary of the feedback from everyone I spoke to or interviewed.

The Provost is indeed a lovely person. I am privy to her sheer brilliance, energy, and enthusiasm almost every day. I was almost tempted to let them know. At the same time, I was hoping their views could be a teachable moment for me. The charm of her excitement at their Induction Ceremony could have made them rue that impersonal relationship even more.

Wow! The Provost has magic!

I read this on their WhatsApp statuses during their Induction event.

But her magic doesn’t have to be for a season or an event. The connection between the Provost and the Excelsior Class can continue to flourish even beyond graduation. They’ve now joined the alumni league to drive a more meaningful relationship with her and the College.

About me…

On a personal note, however, I extend my heartfelt congratulations to the graduates of the Excelsior Class of 2023. They are exceptional. Remarkably, among the top 10 graduates in the MBBS class, 6 are females. That’s an inspiring feat. The bright future that awaits them is a canvas waiting to be painted with their unique contributions to Medicine. I pray their journey is filled with compassion, discovery, and the unwavering pursuit of excellence. They are not just graduates; I believe they are the future of healthcare, and the world is eagerly waiting to see the impact they will make.

In the words of Toni Morrison, it is indeed sheer good fortune to miss somebody long before they leave you, more so, when their time in your life is full of magic and marvel, like that of the Excelsior Class of 2023.

May we find more classes like theirs across all generations.

The End.

You can watch the Excelsior Class Induction Ceremony here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gq8XpnLIBgs&t=5439s

You can watch the Class Documentary (Reflection Video) here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHOQPVPWwdg

Oluwaseun Abimbola, media officer, CoMUI, is a communications & research update manager at ARISE&WIN https://ariseandwin.ng/blog

Add a comment