Improved funding of the health sector is crucial to epidemic preparedness and response. However, inadequate investment in healthcare in Nigeria has affected the sector’s response capacity as most primary health centres (PHCs) lack either personnel or infrastructure — or both — to function efficiently.

On May 15, Ifeoluwa Ademola woke up exhausted and staggered to the toilet with sleepy eyes. After a few minutes inside the toilet, she noticed something unusual; her underwear was soaked with blood. It was at that point that the 26-year-old — who lives in Akute, Ifo LGA, of Ogun state — realised that she was bleeding.

Terrified by the incident, she cleaned up, hurtled out of the toilet and made her way to Ajuwon primary health centre (PHC) to see a doctor; but rather than providing her with succour, her anxiety heightened when she was told at the facility that the doctor was not available.

“I had an abnormal uterine bleeding and I could not explain what it was. The hospital where I registered is a private one, but I am not comfortable with the doctor’s style of not conducting a test before a prescription. So, I opted for a Primary Health Centre (PHC) and the nearest to me was the Ajuwon PHC which was about 30 minutes drive from here,” she told TheCable.

Advertisement

“Moreover, seeing blood at the time I was not supposed to see it was enough to get me worried. Meanwhile, I set out to the PHC only to be told there was no doctor around. I was shocked and disappointed at the same time. I saw the blood over the weekend but decided to visit the hospital on a Monday because I thought there might be no doctor on the seat on a weekend.

“Well, the nurse asked me to submit my phone number and assured me that I would receive a call when he is eventually around. It has been over a month now and I am yet to get a call. Because I take my health seriously, on that same day, I jumped on the bus to a PHC at Ojodu which is about an hour, thirty minutes away from my house.

“When I got there, I waited for hours because there were a lot of patients on ground, and I finally met with the doctor around past 3 pm. The doctor then asked me to do a scan which revealed I had abnormal uterine bleeding. I really think we lack enough medical practitioners in our public hospitals particularly the PHCs. I wouldn’t know if it is the Japa thing but we’re lacking doctors.

Advertisement

“When I walked into the doctor’s office that day, I felt for him. That single doctor must have attended to over 50 persons that day, only one person and the 50 people might have come with different conditions. You can imagine. Till date, the Ajuwon PHC has not called me. Imagine if I waited for the call, I would be bleeding for nothing. Nigeria needs to do better.”

In far away Niger state, prompt access to healthcare across PHCs is a major challenge.

Hadiza Rabiu, a resident of Jedna ward in Paikoro LGA, said the PHC in her community closes by 2 pm, thereby limiting access to healthcare.

“We have a PHC but it is not always accessible because the workers don’t stay there throughout the day. They leave by 2 pm and after that, the facility will no longer be opened for patients. It is a challenge for many women like me and children in my community,” she said.

Advertisement

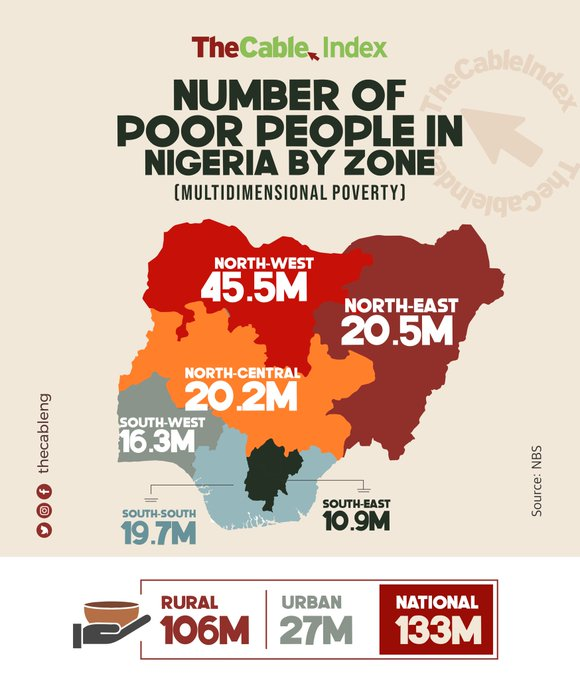

About 133 million Nigerians are multidimensionally poor, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). This situation has left many people with no option than to settle for the PHCs for their health needs.

The experiences of Ademola and Rabiu at the facilities are usually not one to remember. Last year, the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA) estimated that six out of ten Nigerians lack access to quality primary healthcare services. This, the agency, said has worsened disease outbreaks and out-of-pocket expenditure.

The agency also revealed in its March 2023 report that only 1.8% — 463 out of 25,843 — PHCs in the country have the minimum number of required skilled birth attendants (SBA) which is four per facility.

Advertisement

THE FUNDING CHALLENGE

For years, inadequate funding of the health sector in the country has remained a concern for stakeholders. Nigeria has failed to reach the 15 per cent allocation of the annual federal government budget to the health sector — over 20 years after the African Union (AU) members jointly made the resolution at a summit in Abuja.

Advertisement

The country’s highest allocation to the health sector has been seven per cent, which is a far cry from the 2001 declaration. In April, the World Health Organisation (WHO) said the country is “still far from achieving the target”.

This leaves the PHCs and other government-owned hospitals incapacitated to prepare and respond optimally during disease outbreaks.

Advertisement

In 2021, an investigation by TheCable across Ondo and Enugu communities showed that shortage of health personnel, personal protective equipment (PPEs), and infrastructure at PHCs affected the country’s fight against Yellow fever and Lassa fever.

In its March 2023 report, the NPHCDA said although the PHC system has made some notable progress in recent years, “its functionality remains sub-optimal, weakened by several institutional challenges that inhibit its ability to adequately play its pivotal role in ensuring access to care for Nigerians”.

Advertisement

“This situation in the last couple of years has been aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Key amongst these issues are: inadequate human resources with 0.4 physicians per 1,000 people, and 22% of other required healthcare workers available across Nigeria; sub-optimal financing leading to high out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure at 75%; substandard physical infrastructure, wherein 30% of PHCs meet the minimum Level 2 standards, making them unfit for purpose; insufficient demand for PHC services; limited availability of supplies; fragmented supply chains and storage capacity constraints; and subpar data quality impacting the use of data in decision making. These challenges have led to low public confidence, limited effective access to care at the grassroots and under-utilization of the PHC system, pushing the burden to secondary and tertiary systems,” the report added.

Despite this, the priority accorded to the health sector remains low. In the N21.83 trillion 2023 appropriation bill signed into law, for instance, Tracka, the service delivery promotion platform of BudgIT, revealed that N81.7 billion was allocated to the construction of solar streetlights in the 2023 federal capital and constituency projects.

This, according to the organisation, is higher than the total budget allocation to schools and primary health centres, which gulped N77.9 billion and N3.1 billion respectively.

“Nigeria’s child mortality rate is the second-highest in the world, and maternal mortality is at 576 per 100,000 live births, the fourth-highest in the world. In a country plagued with these critical issues, dwindling revenue, and a failing economy, the bogus allocation to streetlights is a gross misplacement of priority,” the report said.

‘NIGERIA’S HEALTH SYSTEM REACTIVE, NOT POSITIONED TO HANDLE DISEASE OUTBREAKS’

Speaking on the health sector, Ifeanyi Ugwuoke, national programme manager of Accountable, Responsive & Capable Government (ARC), said efforts must be put in place to move the country’s health system from its extant “reactive” state.

“The political will to fund health is very low and that is why the country is not meeting the required threshold for funding the sector. Things like cholera, typhoid and other things are rampant all over the country, so it (inadequate funding) has severe implications on the country’s epidemic response and preparedness,” he said.

“Yes, the government tried during COVID-19 but our level of preparedness is always questionable. What we are doing is playing catch-up. We are always reacting to some of these issues by raising emergency funds. So, the system is currently reactive. It’s not strategically positioned to respond to epidemics.”

‘WE HAVE MADE SIGNIFICANT PROGRESS IN EPIDEMIC PREPAREDNESS, RESPONSE’

Addressing concerns around the country’s epidemic preparedness and response, Godwin Ntadom, the chief epidemiologist of Nigeria, said the country has made significant progress since the Ebola and COVID-19 outbreaks in 2014 and 2020 respectively.

“We now have facilities that can take COVID-19 and other samples in the state. Before now, we only have three in the entire country. Not only that, health workers are being trained to respond to emergency operations,” he told TheCable.

“When it comes to preparedness, I can tell you that we are ready. The Ebola outbreak of 2014 met us unexpectedly. By then, we were not really prepared. Also, nobody really expected the COVID pandemic.

“But with those experiences, the country has strengthened its preparedness apparatus. People have been trained. We now have functional labs and we also have enough resources — by this I mean the agencies tasked with combating epidemics are now better funded.

“The awareness about epidemics has increased too and so many international agencies have come in to support activities for preparedness and response. Of recent, there is another initiative by the federal government which is called Strengthening and Utilising Response Groups for Emergencies (SURGE) which is driven by World Health Organisation (WHO).

“They are supporting FG and states in Nigeria to be able to get prepared. This time around, it is not just going to be disease alone but every form of emergency that affects public health. This is to ensure that the country is able to respond to any challenge — ranging from road accidents, flood disasters, and fire outbreaks. The federal government is trying to set up one body that will comprise all the ministries and agencies involved to do this. This will enable them to collaborate as one body to fight whatever outbreak it is.”

Without adequate funding of the PHCs and the health sector at large, the likes of Ademola, Rabiu and other Nigerians will continue to be deprived of quality healthcare, putting them at risk of death.

This report is supported by Nigeria Health Watch.

Add a comment