In a deregulated economy, price determination is left at the mercy of the interactions between the market forces of demand and supply. Meanwhile, government through its agencies serves as the umpire, monitoring the activities of the industry players with a view to ensuring that, they do not unnecessarily profiteer. Students of Economics, whether major, or minor, no matter how academically poor, would always tell you that all the government does, through its (regulatory) agencies, is to ensure that sanity reigns within the business ecosystem. This reinforces the saying that “government has no business in business”.

The most common form of government intervention in this case is to put a price cap on every commodity or service, above which a seller must not go, as well as ensuring adherence to the Service-Level Agreement (SLA). This is in addition to ensuring that the business is conducted in accordance with the regulatory laws and global best practices. In short, the government’s role is to ensure that the “consuming public” is not short-changed, and their safety, not put into jeopardy.

What governments normally do in deregulated economies is to set up regulatory agencies in each of the concerned sectors to superintendent what goes on, in there. But welcome to Nigeria, where regulatory agencies are more concerned about revenue-generation, jettisoning their statutory core responsibilities. The reason is not far-fetched. Most of the revenues collected almost always ends up in either private pockets, or private bank accounts, instead of governments’ coffers. One of the few regulatory agencies in Nigeria that wear the closest semblance of how a regulatory agency operates in a deregulated economy is the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) which oversees the telecommunications industry in the country. It grants operating licence to operators, sells and allocates spectrum to service providers, monitors prices, and ensures that the predetermined “pricing template” is maintained, ensures provision of quality products and services in accordance with the “SLA”, promotes competition, and uphold standard of operation among others. For instance, no telecoms service provider charges how much it likes on any of its products and services, without it being subjected to the laid down processes and procedures. That is why we experience the little semblance of sanity we have in that sector, in Nigeria today, if you discount “dropped calls”, indiscriminate deductions from customers’ accounts often attributed to system error, and unsolicited text messages. Pardon me, if this example does not align with your definition of “a semblance of sanity in an industry like the telecoms”. That is the system to which I have been exposed, both as a customer, and as someone who had worked in the sector for about five years.

Now, let’s talk about the “legendary” petroleum industry that seems to have an impact on every aspect of our national livelihood. The country relies on the sector, to a very large extent, to power its economy. Even, if a product is not impacted by a Petroleum product during its process of production, it surely will, when it comes to distribution (transportation). That is why, whenever the oil and gas sector sneezes, the whole country catches a cold. This is not even talking about it being Nigeria’s major source of forex earning yet.

Advertisement

In the past couple of months, Nigerians have been going through hell, trying to fuel their cars, power their homes and businesses, especially for business entities which operations are heavily energy-dependent. And, there is a method to that suffering to which the people of this country are periodically being subjected, in their quests to benefit from what nature is pleased to have endowed their land with. It normally starts with mild scarcity, occasioned by hoarding. Later, it snowballs into outright scarcity in a manner that is akin to an economic sabotage, before finally making it available again at superlatively exorbitant rates, depending on which part of Nigeria you dwell.

As of today, officially the pump price for Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) in Nigeria is still ₦165 per litre, but the cheapest you can get it is ₦190, a litre. I, was told but, do not know how true it is, that it is still being sold by the state-owned Nigeria National Petroleum Company (NNPC) Limited’s fuelling stations at the official rate of ₦165 per litre whenever they have it. The average rate in the Ilorin Metropolis, for example, is ₦370 per litre, and there is not much difference in the neighbouring States of Ọ̀yọ́, Osun, Ekiti, Kogi and Niger. In parts of Lagos, people are talking, on social media, about it being available at the rate of about ₦400 to ₦500 a litre. All hitherto moribund Fuelling Stations in town are now back in business (of black-marketing). There is a particular one in my neighbourhood that has not dispensed a drop of fuel in the past three years, but has suddenly found its mojo, in the ongoing festival of profiteering by those I call “the Nigerian Petrol Cartel (NPC)”. The price is not even of concern to me, as much as the integrity of their meter is. Some stations have drastically adjusted their meter so much that, if you pay for 20 litres of fuel, you may not actually get more 12 litres into your tank, even though you’d paid for the ordered 20 litres that has been displayed on their meter. Yet, the Minister of State for Petroleum Resources, Timipre Sylva, would come out, tongue-in-cheek, to tell Nigerians that the federal government had not increased the pump price, and that whoever sells above that price is acting contrary to the government directive. But recently, in what could be termed “a Freudian Slip”, he let out what confirmed the worst fear Nigerians harboured, saying he won’t feel bad, paying as much as ₦300 per litre because other countries pay more than that for the same product.

I won’t feel bad buying petrol at N300 a litre — other countries pay more, says Sylva

Advertisement

Meanwhile, he refused to tell Nigerians that, in those other countries, citizen don’t stay up two weeks or more, without public power supply – as a matter of fact, there is always constant public power supply in those countries. There is also a robust public transport system that makes it easy, and cheaper, for residents to commute.

A combination of the defunct, Petroleum Products Pricing Regulatory Agency (PPPRA), Petroleum Equalisation Funds (PEF), and Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) have now been replaced by the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), called “the Authority” is now responsible for upholding standard of measurement by carrying out unscheduled inspection visits to fuelling stations for random checks on their meters’ integrity. They also prevent sharp practices in the industry, among other regulatory functions. The agency is responsible for ensuring that there is sanity in the industry. But nowadays, it seems to exist, as though it does not exist.

Viewing it from the basic, the NNPC, to the best of my knowledge, remains the sole importer of petroleum products in Nigeria at the moment. The company imports, then sells to independent marketers at a subsidised rate to enable Nigerians to buy at the government-approved rate of ₦165 per litre. Yet, these marketers lift the product, and start selling at any price of their individual choices. One would want to ask; where, then, is the regulatory agency – the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), popularly known as the “Authority”, which was birthed by the enactment of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) – 2021? Its officials do not seem to be on duty. Therefore, selling at the approved rate now appears to be an anomaly, rather than the rule.

Advertisement

Getting to even know what the problem is, has been as problematic as the problem itself. Who is in charge (of regulation) of the industry? Is it the government (through its agencies), or the cartel that is holding the country’s economy and the nation’s livelihood by the jugular? If the response says, “it is the government”, in this prevailing circumstance, that would be a perfect example of how not to be in charge.

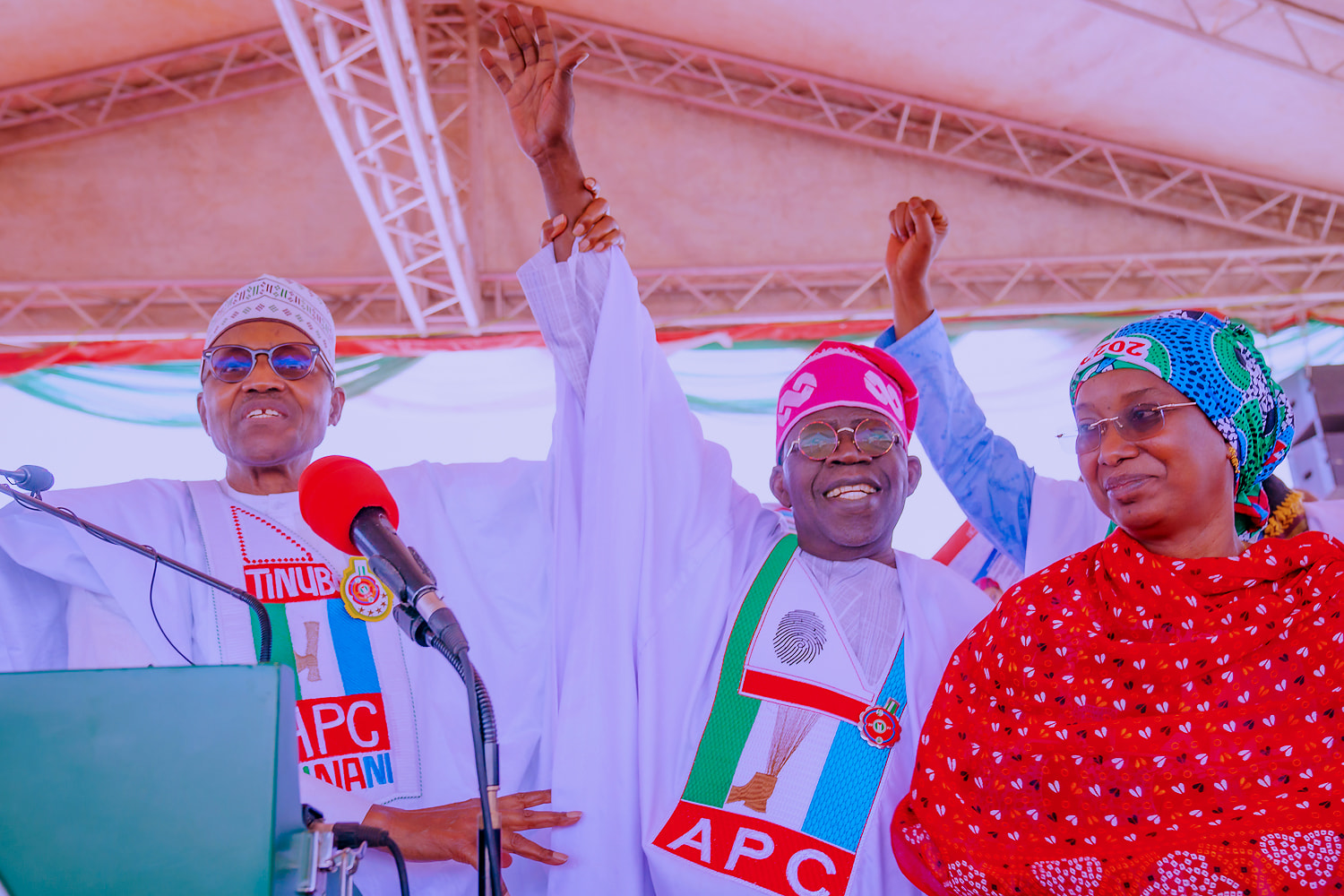

One would shudder to ask; what is the responsibility of the “Authority” (NMDPRA) – an agency that is supposed to regulate the retail sub-sector of the Oil and Gas industry? If the regulatory agency fails in its responsibilities to monitor distribution, and regulate price, after the government had, through the NNPC limited (the sole importer of PMS), paid the subsidy for the product, then what is the job of the Minister? What is the responsibility of the President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, President Muhammadu Buhari, who also doubles as the Senior Minister for Petroleum Resources? Is this how the government will carry out the regulation of a deregulated Petroleum industry, as provided for in the Petroleum Industry Acts (PIA) – 2021? By and large, with my experience in the last six months or so, I can safely conclude, without any fear of equivocation, that everybody is in charge, but in an actual sense, nobody is in charge.

Abubakar writes from Ilorin. He can be reached via 08051388285 or [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.