There are two things I avoid like a plague: water, because of my mastery of swimming, and intellectualism (not in disapproving sense of the word), for similar reason. In other words, my phobia for both, stemmed from my proficiency in handling them.

This, perhaps, might be at the center of my predilection for watching from the sideline when my two erudite friends, Ibrahim Waziri and Auwalu Sani Anwar, were recently exchanging fireworks, on Pax Islamica, the quest of Muslim International Order, one of the most enduring topics among the Muslim intellectuals, for ages.

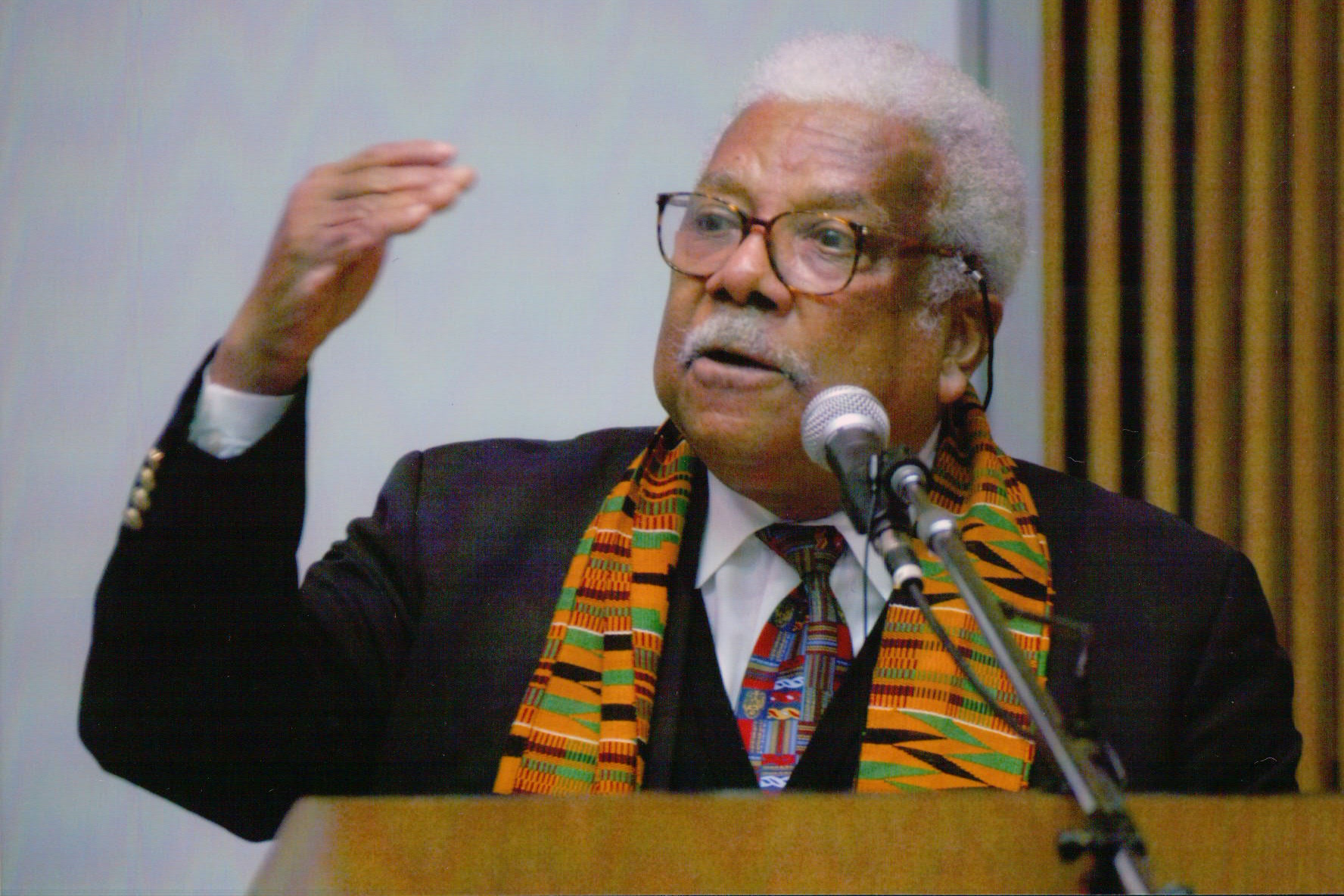

Yet, despite that the topic was almost flogged to death, I found my interest on it revived sooner than I expected. This time around, however, it was another friend, Abdulaziz Abdulaziz who shared a piece, On Poet-presidents and philosopher-Kings, penned by Late Professor Ali Mazrui.

Abdulaziz felt that Malcolm Heath’s Ancient Philosophical Poetics–a book which attracted robust reviews, on a social media forum Waziri coincidentally midwifed– could be better understood with reading some of Mazrui’s works. He was right.

Advertisement

Yet what caught attention most in Mazrui’s article, was a mention of former Senegal’s leader, Late Leopold Senghor whom Mazurui described as “definitely more tolerant than most of his contemporaries who wielded similar power in the third-world countries.”

The scholar, who was apparently trying to establish a nexus between literati and democratic temperaments of some post-colonial African leaders, was of the opinion that those he termed poet-presidents had proven to be more tolerant of dissents than even their peers, who were inclined to claims of being philosopher-kings. He singled out Sanghor and Agostinho Neto of Angola as undisputed cases in point.

In Mazrui’s views, political opposition in Senegal was more open and more articulate than almost anywhere else in Africa during Sanghor’s era. “Although many rivals contested his power in Senegal, he showed a remarkable capacity to absorb other parties and movements.”

Advertisement

But was this relative tolerance due to the fact that he was a poet as well as a philosopher-king? Did Senghor’s literary credentials humanize his style of governance?

Yet Mazrui’s eloquent answers are as striking as his posers.

“In reality, Senegalese Islam was relevant to his poetry and to an under-standing of his political practices,” he noted, adding that “Leopold Senghor presided over a Muslim society which was ecumenical enough to tolerate a Roman Catholic Head of State (Senegal is over 80% Muslim).”

If Mazrui was still alive today, one would have been tempted to ask him to elaborate on the nature of this Senegalese Islam. It might be the only missing part of the already solved puzzle. The nature of Senegal’s , I believe, would provide more insight into the psychology of these Muslims and their inclination to pluralism. Senegal is, no doubt, a country where Sufism has thrived since its arrival in 14th century.

Advertisement

So was there influence of Sufism in Senegalese Islam which displays this remarkable tolerance that even the West is still struggling to fully imbibe?

In Nigeria, for instance, Sokoto Chaliphate– despite being a product of Islamic revivalism– could bequeath to us a Muslim community, who could install and prop up, a Christian head of state, Gen. Yakubu Gowon, for nearly a decade. Gowon is still the longest serving Head of State in Nigeria’s history.

But if there’s a any doubt on the profound impact Sokoto Chalipate had on the mentality of Nigerian Muslim then, this brilliant quote from one the founders of Sokoto Chaliphate, Abdullahi Bin Fodio, could help to clear it.

It wasn’t a coincidence, therefore, when he said, “Power endures with justice even if it is in the hands of an unbeliever, but collapses when injustice pervades even if it is in the hands of a Muslim. “ Nigeria’s political history is replete with several examples that have proven Bin Fodio right.

Advertisement

Thus whether Nigerian Muslims had consciously used this saying as their compass in taking that Gowon decision, what’s not in doubt, however, is the fact that they have successfully demonstrated their capacity to put the maxim in practice– with the Gowon model.

That my late father, who lived and died as a devout Muslim, could name me after Gowon then, without facing any protest at home or anywhere else, was a testimony to how well entrenched moderation was among Muslims in Nigeria.

Advertisement

So it can safely be argued that Nigerian Muslims, like their Senegalese counterparts, had singled out Justice, and indeed, not faith, as the number one leadership requirement. It was a standard set by the founders of Sokoto Chaliphate.

In a paper, Rethinking Citizenship Rights of Non-Muslims in an Islamic State: Rashid al-Ghannish’s contribution to the evolving debate, Abdullah Saeed, copiously quoted Algannishi, a scholar he tagged a neo-revivalist Islamist, as making a case for pluralism.

Advertisement

According to the writer, Ghanniishi was of opinion that one of the main objectives of Islam from the beginning was to establish a just order.

“In the early development of Islam, the most important problems the Prophet, or the Qur’an, had to deal with were social, among them being the forms of oppression committed against the weak sections of society: women, children and slaves. Ghannnshi points out that the term ‘adl and its derivatives appear more than twenty times in the Quran.”

Advertisement

He further argued that it was due to this emphasis on justice that the weak and the Oppressed became the first to profess Islam.

This perhaps gives us an insight, too, into the thought of those who think that pax Islamica, is not a theological requirement in Islam and thus Muslims are better off under a pluralistic system.

While this debate would continue ad infinitum , the modus of operandi adopted by those who chose violent means toward establishing a chaliphate in the society is likely to continue to swell the pluralists’ camp.

That said, many a Muslim who professes to minority ideologies within the fold may fear that his or her doctrinal rights might be trampled upon if the new order is eventually established under the banner of a particular creed.

As a matter of fact, it’s these unfortunates sectarian cleavages within that have contributed to robbing the Muslim world the leadership it deserves– and of course the quest of its international order.

Yet the most significant challenge facing the Muslim world today is curbing the monumental havoc caused by those who embrace violence as a means to achieving the goal establishing caliphate.

Like Socrates feared the influence of poetry, or at least bad poetry, in corrupting societal values, the Muslim world also needs to urgently address the dangers of pedagogy of extremism which have been used as manual for radicalizing youths. But is this also achievable without a strong Muslim leadership at the center? There lies the dilemma.

Add a comment