Obituary of a 41 year old woman. Such obituarues are common in Gokana

Dressed in a red polo shirt carrying the clear message “No Cleanup, No Justice”, Emmah Pii, the village head of Deebon in Bodo community, Gokana local government area of Rivers state, looked more like an activist than a local chief. For him, being alive is a rare smile of fortune as he had almost passed out the previous night.

“You are lucky to see me alive. As you are see me, I’m just a moving corpse. I was passing watery stool throughout the night because of the bad water I drank,” Pii said in a weak tone.

“Pollution is killing us. Two of my classmates are being buried today. If not for the way I’m feeling, I am supposed to attend their burial. In this village, we bury 10 people every week. You cannot live in this place, breathe this air and drink this water and live well as a person. As you are seeing the people here, they are not well at all.”

Bodo is famous for two major oil spills that occurred along the Bodo west flow station in 2008. The 24 and 28 inch Trans Niger Pipeline of the Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) had ruptured, spilling about 560,000 barrels of oil in the creeks over a period of at least 141 days. This resulted in the destruction of around 4,864 mangrove population and became the defining incident for a community that was once green and pristine, making it a cemetery of both aquatic and human lives.

Advertisement

Though it took SPDC years to finally pay a paltry sum of N600,000 per claimant in the community, the impact of the spill continues to take its toll on the lives of villagers.

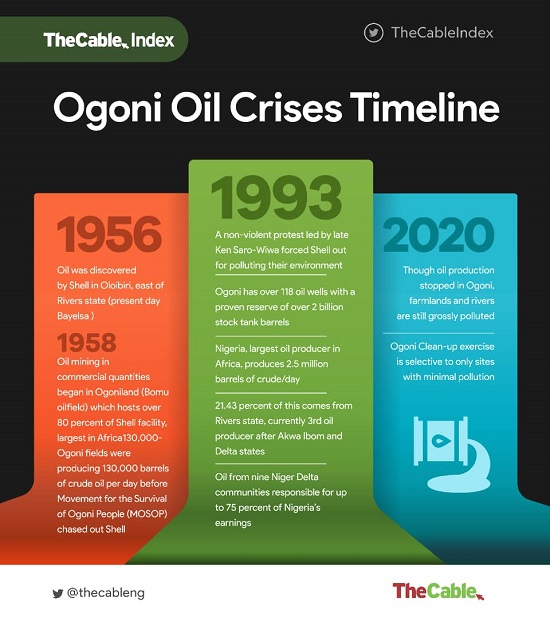

Sitting on huge deposits of crude, Ogoniland is a minority ethnic group of about one million people in four local government areas in Rivers, south of Nigeria.

‘WE DON’T KNOW WHAT IS KILLING US’

Advertisement

Inside the sitting room of Grace Namon, leader of the movement called Ogoni Women of Peace (Gbobiafeefeelo), there is no sofa and the floor is made of bare cement. But hanging low on the unpainted wall is the photograph of the late Ken Saro Wiwa, bearing the message, “You can kill the messenger, but not the message”. This summarises the struggles of the 60-year-old advocate. Her message to the government is to provide alternative water supply as compensation for the pollution of their surface and groundwater.

“The least they can do for poor people like us is to provide common water,” she said. “Nine years after the United Nations told them to provide water for us, we are still drinking poison. The kind of typhoid fever you find here is not common. You will need very strong antibiotics, but we don’t even have money to go to the hospital. Our women are having miscarriages, early menopause, no health registry and our people are dying of strange diseases. We don’t even know what is killing us.”

Namon lives just beside Nigeria’s foremost Bomu manifold, one of the largest in Africa — an oilfield which has an estimated 54 oil wells operated by SPDC. Oil production began there in 1959.

Though the protest led by late Saro Wiwa in 1993 forced SPDC out of that land, government and private-owned (SPDC) pipelines, carrying oil to the country’s export terminal — where Nigeria earns up to $230.65million monthly from crude oil sales — still intermingles with the communities. The pipelines pass through through their creeks, balconies and farmlands. But there are no pipelines carrying water into their homes.

Advertisement

BLACK WELLS

This reporter visited Nisisioken Ogale, another part of Ogoniland spewing with affluence, where community members were so eager to show the kind of water in their wells. However, for some houses, the water in the wells had been blackened by oil. Noble Nwolu, a youth leader in the community, said there is no place in Ogale where you can find good drinking water.

“No borehole is useful here. Some people, ignorantly, are still drinking this water, use it to cook, wash their vegetables, cups and spoons, so they still come in contact with it,” Nwolu said.

Ogale is situated in Eleme local government area — the home of Nigeria’s first refinery and largest export seaport. The affluence flowing out of this land does not flow into the homes of the host community. Rather, what flows into their homes is oil-laden water.

Advertisement

“We experience a lot of strange diseases as a result,” Nwolu continued. “There is one very peculiar one; it is not found anywhere apart from here. It happens amongst women above 60 years. They call it ‘pepper body’. They will constantly feel heat all over their bodies. It is just as if someone rubbed pepper on your body and when the weather is hot, they can’t wear clothes.”

In 2011, a report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) red-flagged one of the Ogoni communities as needing emergency action. The report reads: “Of most immediate concern, community members at Nisisioken Ogale are drinking water from wells that are contaminated with benzene, a known carcinogen, at levels over 900 times above the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline. This contamination warrants emergency action ahead of all other remediation efforts.”

Advertisement

The report further stated that hydrocarbon contamination was found in water taken from 28 wells at 10 communities adjacent to contaminated sites. At seven wells, the samples are at least 1,000 times higher than the Nigerian drinking water standard.

Advertisement

When TheCable visited, it was crystal clear that nine years after, contrary to UNEP’s recommendation to provide eight emergency measures, which included the provision of alternative water supply and a health registry, the people still drink poisonous water and are dying of diseases they sometimes explain as the result of a spiritual or diabolic attack.

SHORT-LIVED WATER PROJECTS DOT COMMUNITIES

Advertisement

Walking through the streets of Ogale, one could see several failed attempts at providing sustainable drinking water for the people. Residents told TheCable that most of the borehole water pumps run dry shortly after being commissioned. Monday Bari, a resident, said some politicians come and sink some boreholes just to get voted into office, adding that the lifespan of such boreholes is as short as the number of hours they spend taking their oath of office.

A set of dry, rusty taps was seen at the site of one NNPC water project on Alueken Farm road in Ogale. Moving a few metres away from there is a big black fallen tank which the villagers said was vandalised by restive community youth.

At Bodo city, Pii pointed to a non-functional, senescent borehole sunk by the defunct Oil Minerals Producing Areas Development Commission (OMPADEC) since 1993 and renovated in 2012.

“Six months after renovation, it stopped working,” said Pii. “We drink water from the rivers and streams. Many times, we don’t even have light to pump from the borehole. And even when we bring it out from the borehole, the smell of petrol is what you perceive.”

Nwolu noted that several organisations have come to sink boreholes. While making reference to some random efforts by the government to supply water, he said: “Three years ago, Rivers state and NDDC renovated the state water board in Alesa but it didn’t get to us here. I learnt the pressure on the pipe was not strong enough to carry it to our community. The water was very good, but it wasn’t evenly distributed.”

“Last year, the Niger Delta River Basin Development Authority came, but nothing. And just this year, one NGO planted water at the depth of 250 metres, but the water is still smelling. In 2019, NDDC dug a borehole powered by solar, but the wind damaged it. So, we try to convert it to electricity. The problem is not the borehole, but no water in Ogale is fit for drinking because of the surface and groundwater contamination.”

ENVIRONMENTAL REFUGEES

Having been chased out of his hometown in Goi — one of the most contaminated spots in Gokana — Eric Bariza Dooh, a high chief in Goi, is bereft of everything else except a little money which he has reserved to fight legal battles with SPDC for the spill that destroyed his entire family fortune.

Now an environmental refugee in another community, Dooh said he will continue to fight.

“HYPREP came here and chased us out of our land because they said it was heavily contaminated. They didn’t give us any compensation or relief materials. They (government) have failed. My father died of frustration after spending 15 years in court with Shell. I have spent seven years to secure the jurisdiction in The Hague, and it took me another four years to get the first precedence against Shell,” he said.

“I will not allow them to de-inherit me when I know my rights. Even things as basic as water, we don’t have. The people are still drinking the contaminated water that UNEP said they shouldn’t drink. I have a borehole in my compound; it is polluted. No borehole in Ogoni has a treatment plant. We are still drinking polluted water. The best the government has done for us is to supply water in rusty pipes and tankers.”

CLEAN-UP OR CLEAN WATER?

Following the recommendations UNEP released in 2011, the Nigerian government set up the first Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP) to implement the recommendations, one of which is to provide alternative water supply, in 2012. But HYPREP was non-functional until June 2016, when a new government flagged off the clean-up programme and restructured HYPREP, after which it began the remediation exercise in 2019.

“The first thing they would have done was to provide alternative means of water,” Dooh said. “I raised this when I was a member of the emergency measures committee during the preparation for the implementation of UNEP report, but they are not doing it because they want to make gains for themselves.”

Agreeing with the community complaints is Nnimo Bassey, a renowned environmentalist and member of the board of trustees of HYPREP. He told TheCable, in a phone interview, that it was regrettable that the people still don’t have water till date.

“It’s rather regrettable that there is no drinking water in the land, because provision of water is one of the first things that should have been done. Water is a priority,” he said.

When contacted, Marvin Dekil, the project coordinator of HYPREP, said the responsibility of providing water supply for the people of Ogoni lies with the Rivers state government and not that of a time-bound, intervention project like HYPREP.

“You seem to believe that it is HYPREP’s duty to provide water for the entire Ogoniland. You have not called the Rivers state ministry of water resources which has been there over these decades to ask them why there is no water even now. They are the people with the responsibility to provide water,” Dekil said.

“And then you leave such people and ask an agency whose mandate is to remediate land to be talking about water. The need to provide water is for very small communities. In that report (UNEP), only a few communities are identified that their groundwater is impacted. So, if you follow that report, you will see it is less than five per cent of Ogoni people.

“But because we wanted more of the people to get water, we went into consultation and collaboration with the Rivers state ministry of water resources. I want you to note that the responsibility to provide water rests with the government, not with a project like us. What we are doing is only intervening, so whatever facility we provide, we will still hand it over to the Rivers state ministry of water resources for sustainability reasons.”

On August 28, Dekil reposted a tweet from HYPREP on his handle, which read: “Yesterday at the PCO, we carried out financial bid opening ceremony for the provision of potable water supply in Ogoni. The evaluation of these bids and award of contracts will follow shortly. Potable water supply to the Ogoni people is expected before the end of the year.”

Yesterday at the PCO, we carried out financial bid opening ceremony for the provision of potable water supply in Ogoni. The evaluation of these bids and award of contracts will follow shortly. Potable water supply to the Ogoni people is expected before the end of the year. pic.twitter.com/MoXL9dALyB

— HYPREP (@HYPREPNigeria) August 28, 2020

But in the phone conversation with TheCable, he gave a different explanation. “We are not supplying water,” he said. “We are installing the facilities. Because when you say you are supplying water now, people might think something else. Once we award the contracts, the companies will move to the communities. The companies will rehabilitate the facilities that will provide water infrastructure, water treatment facilities. Once the facilities are there, the water will start. The contractors will be on site this year.”

In July, a press release on HYPREP’s website noted that six contractors were shortlisted out of 40 who participated in the bid. Digging further, it was found that the process actually started in 2018 with the welcoming of bids from 285 companies to rehabilitate existing potable water schemes in Ogoniland (Eleme, Gokana, Khana and Tai) local government areas.

Out of the 285 companies, the number prequalified was 145, and their mandate is to rehabilitate 10 moribund water scheme that will supply about 10,950,000 litres of water per day to the communities.

Despite the recommendations and series of promises, the people of Ogoniland seem to have resigned themselves to fate as the poisonous water continues to send the young and the old to their early graves.

This special investigative report on environmental and climate justice is supported by Bertha Foundation