Aliyu Abubakar was standing near the reception area inside Kawu primary healthcare centre with a calm demeanour. Baba, as Abubakar is popularly called, wore a purple checkered shirt that looked like it had survived through many wears. In his mid-60s, he still looks agile.

With a pair of glasses dangling from his neck, one could assume that the man was a patient’s family member or perhaps one himself.

But all assumptions were laid to rest after Baba, who could not speak much English at a stretch, introduced himself.

“I used to work here. Now I am retired, but still assisting my colleagues here,” he said with a calm voice almost like he was whispering.

Advertisement

Standing up and pointing at Baba, Yakubu, a health worker at the centre, said on days when the facility’s head referred to as “in charge” is not around, he would call Baba to come and help out.

Despite catering to the needs of eleven communities, the centre operates with a staff of only two community health workers and a laboratory technician.

“More workers are needed here. Baba is over 60 years and should be in his house resting,” Yakubu said somewhat angrily.

Advertisement

The roads leading to Kawu primary healthcare centre in Bwari area council of the federal capital territory are unpaved and rough, and unlike many urban healthcare centres, it lacks a protective fence. Instead, it is bordered by trees and wild vegetation.

Although located at the centre of the community for easy access, the situation at the health facility is nothing but a cry for help.

As soon as one walks through the facility’s doors, the dilapidated state is evident — ceilings hang precariously, damaged and fallen apart. As a result, the roof leaks whenever it rains.

Advertisement

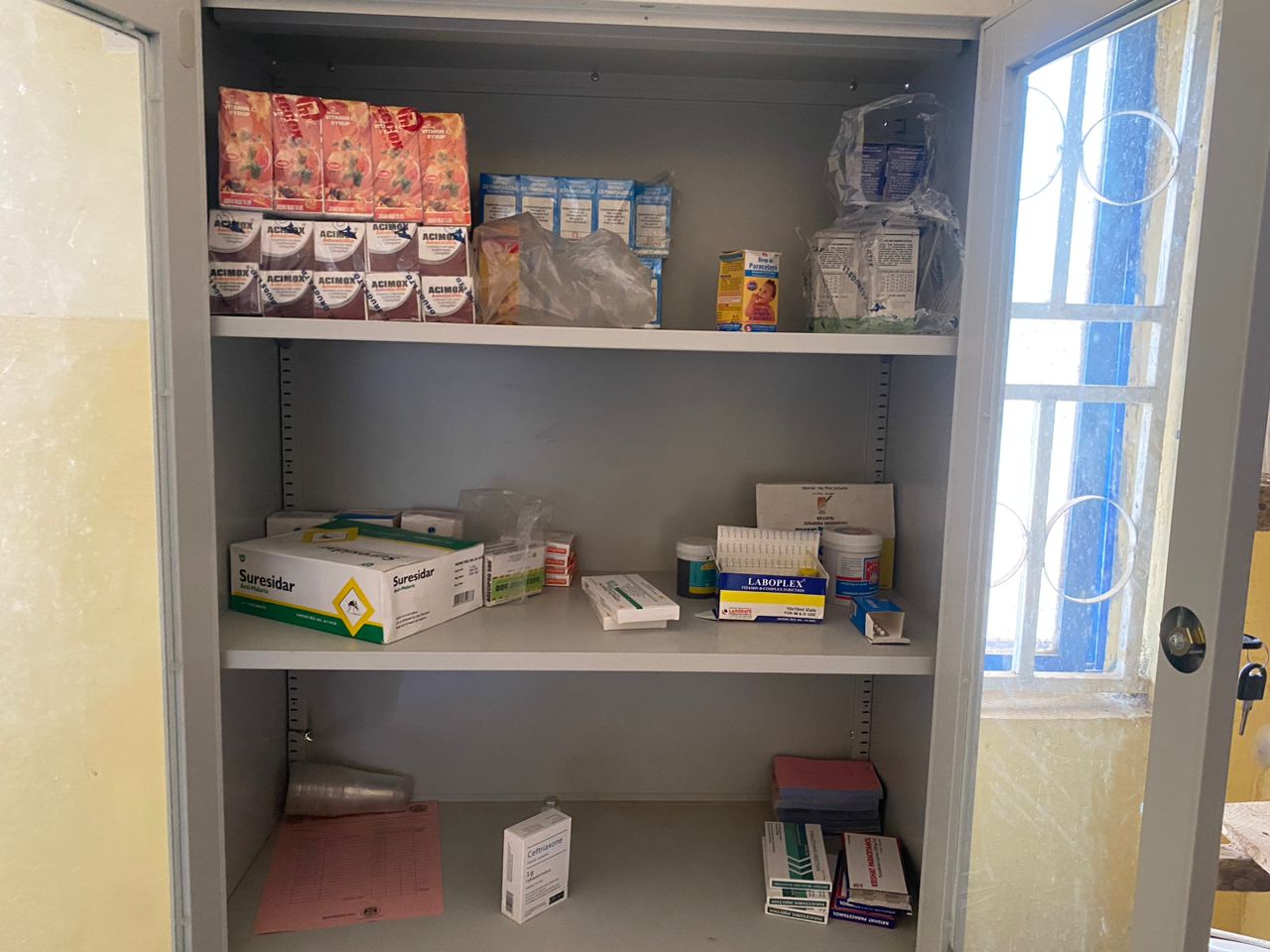

Yakubu said the absence of an electricity supply adds to the struggle, with a solar panel serving as the lifeline for a single medical fridge. The staff said there is constantly a shortage of medicines, forcing the “in charge” to personally fund purchases.

“Sometimes, the in-charge goes to the area council office to ask for money to buy drugs and they will say there is no money,” Yakubu said.

The official said patients are often referred to the general hospital, as the facility lacks the resources to meet their needs.

The health centre, according to the staff, also lacks water, which is vital for hygiene and sanitation. The borehole that should serve as a source of water was destroyed by hoodlums in 2018 and has not been repaired.

Advertisement

Yakubu said the centre was provided with face masks that were distributed to residents at the start of the COVID pandemic; now that the crisis has subsided, everything is back to normal.

The story is not much different at the primary health centre in Kuchiyako, a facility that has seen no form of renovation since its establishment.

Advertisement

Steven, a volunteer staff, said the PHC has only six permanent staff and seven volunteers who only passed through family planning training and do not show up every day.

“In this health centre, we have no water and light,” he said.

Advertisement

“We have not had water for more than five to six years now. We have complained several times to the area council. The recent chairman came here for an outreach some time ago and promised to bring water but we’ve not heard from him since then. We usually buy water from meruwa (water pushers) around here.

“Since we work 24 hours, we need at least 20 health workers here because we need to create shifts so health workers don’t get fatigued.”

Advertisement

Steven said the centre “manages” the medicines available as the head of the facility usually has to collect drugs for free and then pay them back at the end of the month.

“He uses his own money to get the drugs and is usually not able to get enough,” Steven said.

While the situation at Sabon Gari primary healthcare centre, which is located in the township area of Bwari area council, is not perfect, it does present some hope.

At the health centre, which was recently renovated, a health worker happily bragged that the facility was running optimally. She said although the facility has six permanent staff, it also has over 20 volunteers who come regularly.

All the workers, she said, consist of community health workers, midwives and nurses.

In terms of equipment, the health worker said although the government is “trying”, NGOs have shown some support which is still not enough.

She said one of the major challenges currently facing the health centre is that it is no longer capable to cater for the area since the population has increased.

“We need more facilities,” she said.

THE VIRUS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

It was December 2019. People around the world went about their activities without an inkling of the unwelcome disruption that was about to take place — in Wuhan, China, the authorities were battling cases of “pneumonia with unknown causes” that would go on to change the world.

The cases were reported to the World Health Organisation (WHO) on December 31, 2019. On January 7, 2020, the Chinese authorities identified the novel disease as coronavirus, temporarily naming it 2019-nCoV.

The WHO declared the rapidly spreading COVID-19 outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020. The following month, the virus got its official name – COVID-19.

Weeks later, as the virus stealthily crept across borders infecting the unsuspecting masses and leaving governments scrambling, the WHO declared COVID a pandemic — the highest level of alarm under international law. The pandemic showed even the richest countries just how vulnerable and weak their health systems were.

And Nigeria was not spared for long.

On February 27, 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was recorded in Nigeria, making it one of the first countries in Sub-Saharan Africa to identify the virus.

So far, over 266,000 cases and more than 3,000 deaths have been recorded in the country — Lagos, the federal capital territory (FCT), and Rivers state top the list.

After the WHO noticed a downward trend, with population immunity increasing, mortality decreasing and the pressure on health systems easing, on May 5, 2023, it declared that the deadly virus is no longer a global health emergency.

But even as the world heaves a sigh of relief, the WHO has warned that COVID, which has infected more than 760 million people and killed over 6.5 million, will not be the last pandemic the world will encounter and that countries need to be better prepared for the next.

Tedros Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, at a press conference, called on countries to invest in their public health, especially primary health care, as many nations neglected their basic public health systems.

“When the next pandemic comes, the world must be ready, more ready than it was this time. Public health is the foundation of social, economic and political stability. That means investing in population-based services for preventing, detecting and responding to diseases,” he said.

NO LIGHT, NO WATER IN LAGOS PHC

Located in Egbiri, one of the communities in Ayobo, a suburb town in Lagos state, Ayobo Primary Health Centre (PHC) serves as the only health facility for its residents.

The dilapidated roads leading to the community, marred by deep gullies caused by erosion, make it difficult for residents to access the health centre.

The absence of a protective fence frequently results in the intrusion of domestic animals, compromising hygiene and safety standards.

Sandra, a nurse at the centre, told TheCable that the PHC operates without essential resources such as electricity and water.

During a visit to the centre, some patients, mostly women, were discussing how they were going to urinate inside a plastic container and dispose of it at a later time.

Sandra said to minimise the challenge of lack of water, a selfless community member decided to deliver jerry cans of water intermittently to the centre.

The health worker also disclosed that with only four health workers in the centre and six volunteers, the PHC only does “minor treatments and tests for malaria”.

“There is no power supply in this centre. Our two medical fridges are powered by solar panels. At the moment, only one of the fridges is working, the other one is faulty. We are facing a lot of challenges at the centre; there is no power and water supply. Many of our equipment is not in good shape. Patients normally complain about it,” the nurse said.

“There is no doctor here. We refer medical issues that are beyond us to other hospitals.”

She said her last training as a healthcare worker was in 2018.

At Agbelekale PHC, a project signpost right in front of the facility shows that it was recently renovated. The facility, according to Obadeyi Adeyinka, a staff nurse, has adequate power, a water supply and two medical fridges, which are powered by solar panels.

She said the Lagos state government has improved the disbursement of drugs, vaccines, and medical materials to the facility since the COVID pandemic.

Adeyinka said the facility is currently giving out COVID-19 vaccines and other vaccines to residents of the community as part of the effort to achieve herd immunity against COVID-19 and other ailments.

“With what I have observed so far, the Lagos state government has been responding well to improve the operations of this facility,” she said.

“In terms of drugs and other medical materials, we usually get enough supplies.

“We are currently giving COVID-19 vaccines to residents. Our health workers and other volunteers left for the field some minutes before you entered to give out COVID-19 vaccines.”

‘MANAGEMENT OF RIVERS PHC IN GOD’S HANDS’

On a visit to Ahoada East Primary Healthcare Centre, a health worker who asked for anonymity said while the government sometimes purchases and installs medical equipment in the centre, management and maintenance is a problem.

“The equipment may work the week it was installed. Then, you start witnessing power failure. Before you know what is happening, the equipment is grounded because there is no electricity to power them and also no maintenance or servicing.

The health worker said the management of the centre is simply in “God’s hands” as complaining makes no difference.

For disease outbreaks, she said what the government usually does is a “fire brigade approach” since they only start responding when the situation escalates.

A female health worker, Madam Roseline, said those at the managerial level receive drugs and send them to the health centre.

“Sometimes, we might be here waiting for drugs while those at the managerial level have not gotten drugs or logistics for drugs. At this point, there is nothing anyone can do,” she said.

She also decried the bureaucratic bottleneck that affects the maintenance of the hospital facilities with some beds and mattresses no longer good for usage.

In the more urban part of Rivers state is Mgbuoshimini Primary Healthcare Centre, where Glory Emmanuel, a nursing mother, complained that after paying the bill for some medication at the centre, she was told at the pharmacy that drugs were not available.

“The pharmacist told me there were no drugs, that I should go outside and buy them. We go to the health centre because we believe that any drug we receive is original. So, when you tell a patient like me to go and get the drugs outside, it means that there is nothing in our health centres,” she said.

Glory said while one is usually berated for not seeking proper medical care, “when you go there, you don’t get satisfactory services.”

The story is somewhat different in the Omoku Primary Health Centre in Ogba/Egbema/Ndoni LGA of Rivers. The health workers commended the management of the PHC for its commitment to improved services.

One of the health workers, who introduced herself simply as Blessing, described the health centre as “standard”.

“Omoku health centre is qualified for anything and the nurses are hardworking. Whenever you need them, you will see them. You cannot go to the health centre without seeing anybody. There are people (workers) to attend to patients in the morning, afternoon and night,” she said.

The patients don’t have a choice. They either have to endure the state of the facilities or find their way to the Rivers State University Teaching Hospital (RSUTH) popularly known as Braithwaite Memorial Hospital (BMH), in Port Harcourt City.

THE FUNDING AND GOVERNANCE PROBLEM

Primary healthcare is the most important stage in healthcare service delivery as it is the first level of contact at the community level and where minor health challenges with the potential of escalation are detected early.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), primary healthcare is critical to make health systems more resilient to situations of crisis, more proactive in detecting early signs of epidemics and more prepared to act early in response to surges in demand for services.

The organisation also said PHC is the “front door” of the health system and “provides the foundation for the strengthening of the essential public health functions to confront public health crises such as COVID-19”.

But the poor state of some of the 30,000 PHCs across the 774 LGAs in Nigeria means it will be difficult for the country to respond to future outbreaks and may spend more in its eventual response.

Experts have blamed the poor state of these facilities on a funding deficit.

In April 2001, the African Union (AU) countries met in Abuja and set a target of at least 15 per cent of their yearly budget to improve the health sector. But Nigeria has constantly failed to meet the target.

As a commitment to universal health coverage, section 11 of the National Health Act (NHAct) of 2014 mandates the establishment of a basic health care provision fund (BHCPF) to support the effective delivery of primary and secondary health care services in Nigeria.

In accordance with the act, the BHCPF is drawn from an annual grant from the federal government, of not less than one per cent (1%) of the consolidated revenue fund (CRF), grants by international donor partners and funds from any other source, inclusive of the private sector.

The overall objective of the BHCPF is to ensure the provision of a basic minimum package of health services, (BMPHS), strengthen the primary health care system and provide emergency medical treatment.

Fifty per cent of the BHCPF is to be disbursed through the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) for the provision of a BMPHS in eligible primary and secondary health care facilities, 45 per cent is to be disbursed through the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) for the provision of essential drugs, vaccines, consumables, maintenance of facilities, laboratory, equipment and transport for eligible primary health care facilities and the remaining five per cent through the National Emergency Medical Treatment Committee (NEMTC) for the provision of emergency medical treatment.

Is this helping PHCs?

Ayodeji Ajiboye, a senior health economist at the World Bank, told TheCable that the healthcare sector in Nigeria still suffers from inadequate funding, including a lack of investment in primary health care by the states.

Ajiboye said the Nigerian federal government expanded its mandate to fund primary health care through the BHCPF; but even when funds are made available, it is not sufficient.

He said a significant portion of state funds allocated to health is primarily utilised to cover the salaries of healthcare workers, leaving little left for operational costs and capital projects which might be used to improve the state of the primary health facilities.

“You find that they do not have the resources to buy drugs and consumables that they need. They usually will receive this support from the states. But a lot of times, it is not regular. It’s not sufficient and doesn’t come on time,” he said.

Ajiboye said efforts are, however, being made by the government at the national level to address some of these challenges through direct facility financing (DFF) — a component of the BHCPF which provides funds per quarter to one select facility per ward.

In terms of what needs to be done, the senior health economist said the direct facility financing needs to be expanded to more facilities and the amount needs to be reviewed.

“Because the legacy issues of the poor state of health facilities have been on for a very long time. Even if you give them this operating budget, support, it’s probably not sufficient,” he said.

“There needs to be some seed capital, funding that goes to this facility to upgrade them, make sure they have good equipment, and make sure they are attractive and signal quality.”

Ajiboye said in preparing for future pandemics, Nigeria needs to have a well-functioning and integrated healthcare system.

He added that there need to be investments even beyond the primary healthcare level, in a solid health surveillance system, to improve disease detection and response in Nigeria.

Ifeanyi Nsofor, global health expert and senior new voices fellow at Aspen Institute, believes there is a disparity between primary healthcare in urban and rural areas due to poor governance that exists as you move farther away from the capital.

Primary health care, he said, should be in the purview of local government councils of states but the councils themselves are either dysfunctional or non-existent.

“In Nigeria where our focus should be on states, but because of a powerful presidency, all the focus is on Abuja. Everyone wants to know who the president will be but just a few people want to know who the local government chairman or supervisory councillor for health will be. Governors over the years have emasculated local government councils. How many local government councils have any elected leadership? What then happens is that federal government then tries to intervene through all sorts of agencies that should not be in existence if we have functional local government councils,” he said.

Nsofor said what happens in Nigeria is that the government is taken unawares by disease outbreaks even when such diseases are not strange.

The health expert said for Nigeria to be prepared for pandemics, primary health care needs to be functional enough for people to visit them and receive proper care.

“Once there is no structure, we are open to any disease that comes. The government needs to invest in primary health care and ensure the political structures are right. The WHO said sometime in 2018 that universal health coverage and global health security are two sides of the same coin. You can’t have one without the other. As long as we have a dysfunctional primary health care system in Nigeria when people who are sick cannot go for care in primary health centres, then we’re not prepared for pandemics” he said.

In Nigeria, many primary health care centres that are the first point of contact for people in communities lie in neglect and ruins. Cracks need to be mended and foundations need to be fortified to ensure a resilient defence for when a new enemy — another pandemic — attacks.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) as part of its Public Health Reporting Corps initiative.

Add a comment