Investigative journalist ‘Fisayo Soyombo spent 10 weeks tracing the deaths, disappearances and injuries from the military intervention in the Lekki Toll Gate protest of October 20, 2020. In the second of this three-part series, he names some of the dead and reveals their faces. He also documents their final moments and what their passing means to their friends, families, loved ones and the acquaintances they made at the protest ground.

VIEWER DISCRETION ADVISED

Put the blame on God

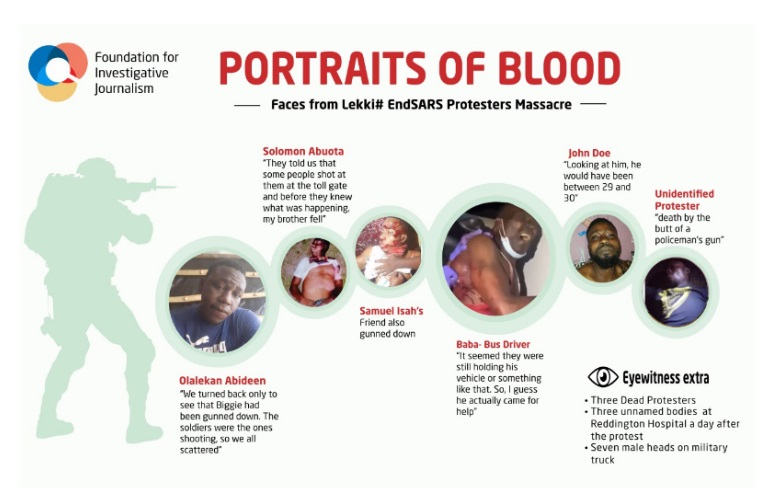

OLALEKAN ‘BIGGIE’ ABIDEEN (1)

Advertisement

Had Olalekan ‘Biggie’ Abideen and his friend left the Lekki Toll Gate five minutes earlier than they attempted on October 20, both of them would have been alive today. By the time they finally left, it was a little too late.

“We were about going home at that late hour when we heard the sound of gunshots,” his friend and fellow protester told a journalist disguised as a sympathizer. “We turned back only to see that Biggie had been gunned down. The soldiers were the ones shooting, so we all scattered.”

Advertisement

His friend didn’t say more than that. As a matter of fact, back then, October 29,2020, nobody else wanted to speak about the death publicly, fearing it could lead to their disappearance or death, as it happened to Delight’s neighbours and two of Joshua Ossai’s friends. In the previous week — the third in October — everyone in the neighbourhoood had shunned questions on whether anyone of them was killed at the toll gate or not. But an undercover approach yielded revelations about two deaths — Biggie’s and Matthew Egop’s. However, FIJ soon found out Egop was killed at Jakande Bus Stop — not Lekki — on the eve of the Lekki Toll Gate shootings. Several weeks after, Biggie’s family are still smarting from his passing.

“I spoke with him that night and he told me his location. It was shortly after that conversation that they informed me something had happened to him. I screamed that it was a lie,” his mum told sympathisers, unaware one of them is a journalist. “I called a bike man to take me to the place but I fell down thrice before we got there.”

Biggie’s mum was doing laundry in her small shop where she sold drinks and spirits at a market some 1km away from Jakande Roundabout along Lekki-Ajah Expressway, but she abandoned it to discuss her loss.

Advertisement

“Look at how bad my leg is,” she says, revealing a swelling to her listeners. “Walking is still a challenge for me.”

So it was for the deceased’s daughter, who fainted and landed in a gutter when the news of Biggie’s demise was broken to her. Neighbours had a terribly hard time extricating her from the culvert. When she regained consciousness, she wouldn’t stop asking grandma for her dad’s whereabouts.

Biggie’s kids, a boy and a girl, have since been withdrawn from school. But there are even more pressing issues to sort out. The family still haven’t come to terms with his passing. When his mum informed them, they told her to “produce our child”.

“I asked if I was responsible for his death,” the grieving woman says. “Not their fault, though; it’s God I blame.”

Advertisement

Invited to Come and Die in Lagos… All the Way from Adamawa

ABOUTA SOLOMON, 20 (2)

Advertisement

Nathaniel Solomon, 33, encouraged his brother Abouta to jettison life in their native Mubi North Local Government Area of Adamawa State for the greener pastures of Lagos. Life in the village was tough on Abouta. There was no job; his aged parents had no means of supporting him. But Nathaniel had recently opened a car wash in Lagos. If Abouta could man it, he reasoned, then half his problems were solved. Abouta agreed to come. In June 2019, he made the daylong road trip to Lagos. It turned out to be an appointment with death!

Advertisement

Abouta joined his brother at Marwa Waterside, Lekki, proving not only a decent manager of the car wash but also a dutiful caregiver to Nathaniel’s kids. In addition, he had a telepathic relationship with his brother. No surprise, therefore, that while Abouta was protesting at the Lekki Toll Gate on the night of October 20, his brother could not concentrate on work because he had “a strange feeling and unexplained body weakness”.

Nathaniel recalls telling his friends that his body was weak and he didn’t know why. Some 30 minutes after, three people in the neighbourhood ran in to break a sad news.

Advertisement

“They told us that some people shot at them at the toll gate and before they knew what was happening, my brother fell,” Nathaniel says in pain-laden pitch. “They said Abouta had been killed. Four of them went to the protest from the neighbourhood but he alone died.”

Although he was speaking on December 15 — almost two months after the tragedy — Nathaniel clenched his teeth intermittently, his eyes reddened by grief, his voice weakened by the sheer memory of it all.

“When we finally got to his corpse, I fainted but I was subsequently resuscitated,” he tells FIJ. “We arranged for a vehicle to take his body to St Paul’s Mortuary, Oyingbo. The next day, we took his body to the village in Adamawa and buried him around 5pm on October 22nd.”

Any preventable death is painful, but Abouta’s is far worse. Until October 20, his mother had lost six of her eight children. His sudden demise leaves Nathaniel as the poor woman’s ‘last man standing’. It’s an irreplaceable loss.

“Honestly, I am feeling bad because it’s like even if someone gave me everything in this country, I will never be happy because this is my younger brother that I am proud of,” laments Nathaniel. “He made me happy whenever I saw him. Now, I feel bad because anything I do now cannot favour me because if I become wealthy, my brother cannot inherit me when I’m gone.”

Nathaniel sorely misses the man who took care of his kids during his frequent absence from home, who respected everyone, who never wanted to fight anyone.

“My brother protested at the toll gate for our good. I was there on some days too,” he says.

Ten days before Abouta’s killing, the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS), released a statement claiming knowledge that “some internet fraudsters, in a bid to continue perpetrating their criminal acts, are mobilising hoodlums to protest against the activities of SARS”. This perspective was shared by the Arewa Youths Consultative Forum (AYCF), which, in fact, said “a close look at the types of persons masquerading as protesters would reveal that they are there to protect the hidden interests of high-profile fraudsters, aka Yahoo Boys, thugs, street urchins and their collaborators”.

But Nathaniel maintains his brother was none of these.

“Abouta was not a yahoo boy or street urchin. He was an innocent person,” he says. “My brother had respect. He avoided fighting with people. I know his character. He was good to me and to others. He was a nice young man.”

Nathaniel “cannot point at anything bad about Abouta”. “He used to wash my clothes,” he says. “He would take care of my children when my wife and I were not at home. Now, no one helps me with that. My mom is aged; she cannot do that for me and [even if she wanted to,] there is no one to help her on the farm.”

“Hin Don Die”

IFEANYI (4)

It was no coincidence that Akin Kolawole and Ifeanyi struck up immediate friendship when they bumped into each other around the Lekki Toll Gate on October 20. Each spotted an Afro and a bushy beard. They were both creatives. They had both been previously profiled and harassed — not once, not twice — by SARS officials. Akin, 25, said Ifeanyi was soft-spoken but even he, as he recalled that traumatic experience 10 weeks later, spoke as softly as humans come. Apart from one dying and the other living, there isn’t much to choose between the duo.

When soldiers arrived at the toll gate that night, Akin and Ifeanyi raised their flags and sang the national anthem as the protest coordinators had instructed the crowd to. But when the soldiers opened fire, they fled.

“So we were all together, myself and Ifeanyi, at every point in time. We ducked when the soldiers shot. When the shooting ceased, we ran,” Akin says while recounting Ifeanyi’s last moments in an interview with FIJ on December 30.

“We always ensured we were down and tried to stay down but at some point, the shootings had subsided, so we fled. We didn’t even know where we were running to but we just kept on but we ensured we were not very far from each other.”

Ifeanyi was ahead of Akin in the race. Suddenly, Akin discovered he had overtaken him. Not only that, his friend was no longer running beside him. He turned back to see Ifeanyi had dropped to the floor and hear someone scream: “Hin don die.”

“The thing I remember vividly was I was in front and he was behind as we were running,” says Akin. “You are ensuring that you stay alive and then the next thing you hear is ‘him don die’. I saw blood; he was in a pool of blood. I looked back and I saw he was the guy I was with. It was a horrifying experience.”

How much of Ifeanyi does Akin know — and remember?

“One day is not just enough to know a couple of things about people, but one thing I got from him is he was a graphics designer. He was fair in complexion; he had a bushy hair — kind of like Afro — and full beards.” he says. “Look, he was killed the very first day we met so I don’t know too much about him! But looking at him, he was such a gentleman who couldn’t hurt a fly. We both wanted a better government… we wanted our voices heard. He told me had been harassed by SARS a couple of times on the Island — that’s why he joined the protest.”

The interview is holding ten weeks after the incident, but Akin has not recovered from the trauma of Ifeanyi’s death and his own narrow escape. “I have to be honest with you, I haven’t recovered,” he says, “because I feel like when you face death, it’s different from when you hear about it.”

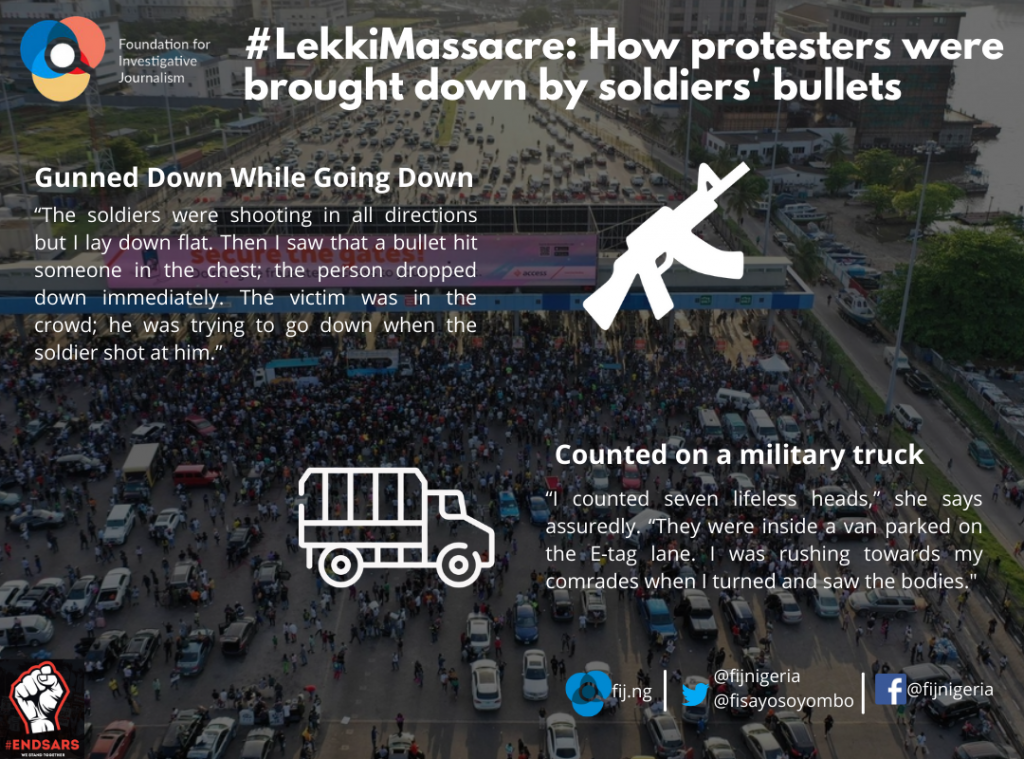

Gunned Down While Going Down

UNIDENTIFIED (5)

Four years of pent-up anger pushed Freeborn Ofurie to join the Lekki Toll Gate protest four days after it kicked off. Back in 2016, Ofurie was arrested by SARS officials after “two sophisticated phones” were found on him. In his mid-thirties at the time, Ofurie had never set foot on a police station much less spend a day there. This time, he spent three.

“I was locked up for three days and I spent over N200,000 to regain my freedom,” he says, “so when I heard about the #EndSARS movement, I got upset and joined after four days.”

Ofurie joined a group that volunteered to sweep and clean the protest ground daily. Therefore, he was present in the evening of October 20 when soldiers arrived at the toll gate. When the shootings began, he hid himself behind the iron barricade demarcating the main road from the pedestrian lane.

“I was behind the Lekki Concession Company (LCC) barricade, so I hid there, just very close to the toll gate. So I got a good glimpse of what happened,” he tells FIJ. “The soldiers were shooting in all directions but I lay down flat. Then I saw that a bullet hit someone in the chest; the person dropped down immediately. The victim was in the crowd; he was trying to go down when the soldier shot at him.”

Ofurie saw “the particular soldier” who pulled the trigger; but since it was dark, only the soldier’s cap was quite visible to him.

“The soldiers were filming the incident themselves,” he says, so I told myself that since they had killed one person in my presence, they were going to kill more. That’s why I pulled myself out.”

Had the circumstances been different, he himself may have been killed when soldiers discovered him in hiding. “A female soldier dressed in black mufti all through was filming,” he recalls. “What saved me was that when they pointed a gun at me, I decided to lie down, so they kind of felt I wasn’t a threat.”

Brought in Dead to Reddington!

THREE UNNAMED BODIES (6, 7, 8)

On October 23 — three days after the protests were forcefully halted by soldiers’ bullets — a doctor with Reddington Hospital located at 15 Admiralty Way, Lekki Phase I, Lagos, confirmed that 10 supposedly injured gunshot victims were brought to the hospital on the night of October 20, but three of them were Brought In Dead (BID).

“I saw 10 bodies with my own eyes and three of them were dead by the time they got here,” said the doctor, who asked not to be named as it would cost him his job. “But I do not know if more bodies were brought in before or after the ones I saw. I’ve only told you what I know.”

Asked why the hospital did not react when Babajide Sanwo-Olu, Governor of the state, said on October 21 that only one person had died at Reddington, the doctor said the hospital had been warned by the Governor not to announce any death and the hospital management had in turn informed its staff to act likewise.

The doctor declined to answer further questions, saying doing so “will definitely give me out”. The doctor maintained being in possession of “evidence of the deaths” but vowed that even though it is impossible to speak out now, it would eventually happen “someday in the future”.

A new development three days after the interaction with the doctor seemed to validate the doctor’s claims. On that day — October 26 — another Reddington doctor asked to be excused from a gathering of friends to attend an emergency meeting convened by the management of the hospital. The feedback from the doctor after the meeting was that the hospital warned them to avoid talking to the media, ensure their social media accounts were not compromised and mind their business. “We were told to just come in, do our jobs and go home,” the doctor said.

On Saturday January 23, FIJ contacted Reddington Hospital for comments, but a woman who answered the phone and simply identified herself as Chantelle, said: “They [including the PRO] are not open on weekends, they are not in the office today, so you will have to call back by Monday.” When FIJ persisted, she asked what the matter was, and was duly told it was about the toll plaza incident of October 20. Still, she repeated the line: “They’re not in the office today.”

FIJ call three times on Monday January 25, but in each occasion the receiver said the PRO was “not on seat” [sic].

Similarly, FIJ attempted to get the comments of Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu, through Gboyega Akosile, his Chief Press Secretary, but the response was: “Everything is before the panel, so Mr. Governor is not making any comments. Thank you.”

Counted on a military truck

SEVEN MALE HEADS (9 – 15)

Kamsi — first introduced to you in Part 1 — was not intentionally seeking to establish what was going on in and around a military van parked on the Mainland-Island lane of the toll gate, very close to the LCC. It was just providence. Her intent was to link up with other protest coordinators to devise how to secure an ambulance to dispense first aid to protesters with gunshot wounds. Instead of an ambulance, she found corpses.

“I counted seven lifeless heads,” she says assuredly. “They were inside a van parked on the E-tag lane. I was rushing towards my comrades when I turned and saw the bodies. The bodies were stacked, so I counted one by one. They were seven, all male.

I deliberately counted the heads — not the legs. Some were shot in the head, some in the chest, some in the neck.”

How could the soldiers have afforded Kamsi ample time for such counting? “They were focusing on the opposite direction,” she says. “They backed the truck. Their attention on the protesters because they were trying to surround us by forming themselves into a barricade.”

Not Kamsi or anyone else ever saw any of the corpses again.

Rechristened in death

JOHN DOE (16)

In the early hours of Wednesday October 21, Kamsi and a few other protesters laid siege to Reddington Hospital on Admiralty Way to demand the release of bodies of slain protesters. Word had gone round over the night that some dead and injured protesters were at Reddington, but the lead doctor on duty denied.

“We went there and found a lot of injured protesters on the ground,” Kamsi recalls. “I was like, what is going on? I asked to see the dead ones? They led us to a doctor but the doctor did not give us any concrete answers.”

Miffed, Kamsi started filming the hospital premises. Other protesters threatened to escalate the situation to the media and get the hospital shut down. “Perhaps out of fear”, the hospital showed the protesters a lifeless body. His identity was unknown but the doctor named him “John Doe”. Just for the moment.

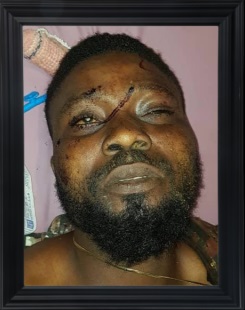

Dark, richly bearded and necklace-adorning, John Doe appeared to have nursed a physical injury in his lifetime as, in death, one eye closed while the other didn’t. He had patches of blood stains on his body — most markedly his left temple and two chins — the longest extending from his left eyebrow to the underside of his right eye. The soldiers’ bullets hit him in the back.

“Looking at him, he would have been between 29 and 30,” says Kamsi. “Thirty-something at most.”

Death by the butt of a policeman’s gun

UNIDENTIFIED CORPSE (17)

At about 11pm in the night of October 20, after the trigger-happy soldiers had departed the toll gate, four vans bearing a horde of policemen drove into the midst of #EndSARS protesters sitting in a group on the lane leading to Victoria Island. The group dispersed as soon as it suspected it was the target of the policemen, four of whom donned SARS vests. But one young man wasn’t so lucky; they got a hold of him before he could flee. They repeatedly beat him and hit their guns on his head.

“He was trying to gasp for his breath, trying to hold on a little longer but he couldn’t,” recalls Sam Isah, a fashion designer who witnessed the incident. “We noticed the guy wasn’t moving.”

Some protesters converged on the spot where his body lay, retrieved it, dumped it on the median of the road and invited the policemen to come have it. “You guys have killed this young man, come have his body,” the protesters screamed.

Although nobody knew his name, the deceased, ostensibly in his late 20s, was dark-skinned, wore a low haircut and had a clean shave.

Killed for protesting a death

UNIDENTIFIED CORPSE (18)

As the protesters turned back after turning in the body to the Police, gunshots were fired in their direction by the Police. They started running but one of them was hit in the head; he dropped to the ground and died instantly, a Nigerian flag clutched in his hands.

Although Sam never got to ask for the deceased’s name, he remembers he was in his early twenties and died spotting a t-shirt and a jean trouser.

“I don’t know anything about him personally,” says Sam. “That night, we met a lot of people we never knew from anywhere.”

Sam started to leave the scene but couldn’t just abandon the body of a young man he had spent some hours with at the protest ground and was talking with only minutes earlier. He returned to record a 23-second video of the twenty-something-year-old.

“I had to go back to take his video because I needed something to remember him with,” he says. “When I was recording it, other guys came. That was when the policemen left.”

The deceased’s body would later end up at Reddington hospital, sighted by Sam the following morning and referenced by Babajide Sanwo-Olu, Governor of Lagos state, who tweeted at exactly 11:30am on Wednesday October 21: “Information reaching us now is that a life was lost at Reddington Hospital due to blunt force trauma to the head. It is an unfortunate and very sad loss. This is an isolated case. We are still investigating if he was a protester.”

Apart from not being an isolated case as claimed by the Governor, Sam insists the death happened the previous day — not on Wednesday.

“Yes, that was the dead body I saw at Reddington the following morning,” he says. “It was lying on the floor. They had already removed his pair of jeans and t-shirt, leaving just the boxer shorts.”

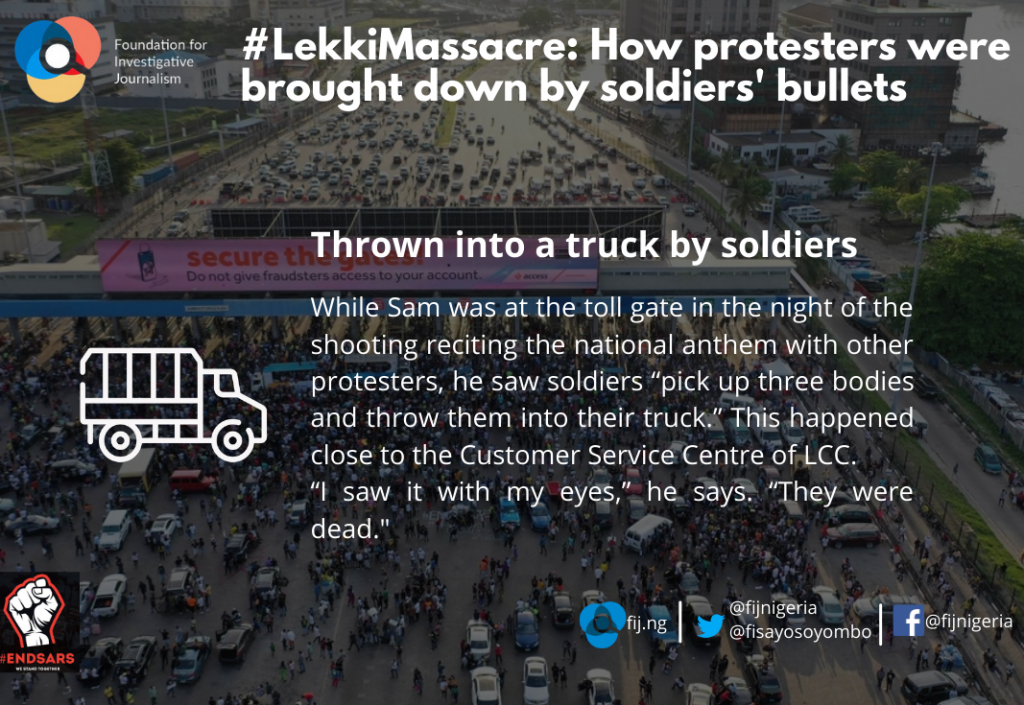

THREE DEAD PROTESTERS (19, 20,21)

While Sam was at the toll gate in the night of the shooting reciting the national anthem with other protesters, he saw soldiers “pick up three bodies and throw them into their truck.” This happened close to the Customer Service Centre of LCC.

“I saw it with my eyes,” he says. “They were dead. I can tell you confidently that those guys were not alive — because you can’t just carry a living being from the floor and fling his body into the truck. There would be a form of resistance or something, but in this case there was none.”

Asked to clearly describe exactly what kind of vehicle the bodies were thrown into, Sam insists it wasn’t a car or a van. “It was a truck,” he says,” a truck that had the back of a pick-up.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: FIJ initially included an elderly man widely known as ‘Baba’ on the list, but new information available to us show that the man eventually survived his gunshot wounds. His entry was accordingly deleted.

The 20 deaths we have listed here are clearly not definitive; this is an uncompleted project. There are a number of existing leads we have been unable to track: people who were at the toll gate but haven’t been seen since the massacre, those who suffered losses but are unwilling to go on record, the number of protesters killed while escaping through the waterway, and the third-party accounts of deaths whose primary witnesses we ran out of time in tracking. For these reasons and many more, we are quite convinced that just like the Zaria massacre which the Army denied until it was proven by the Kaduna State Government-formed Commission for Judicial Inquiry, the deaths from the Lekki massacre are definitely higher than we have listed. We know, matter-of-factly, that we have only managed to scratch the surface of this humongous story.

This is the second of a three-part series. You may read Part I here. This investigation was produced with funding support from Anap Foundation in furtherance of their objective of promoting Good Governance

Add a comment