On Friday, a protester in Lagos demanded an end to attacks on free press in Nigeria

During elections, protests, and other major events, journalists are often at the forefront of documenting and projecting the happenings to the world.

In Nigeria, the 2020 #EndSARS protest, the 2023 general election, and other important national issues were not exempt. As the ongoing #EndBadGovernance protest across the country continues, journalists have actively covered the event and other sidelines.

On August 1, Nigerians started a 10-day nationwide protest to express their grievances over lingering economic hardship in the country.

During the demonstration, journalists were harassed and their phones smashed by security operatives for doing their jobs. While others had their phones and cameras seized, some were reportedly whisked to police stations “for safety”.

Advertisement

This is happening despite repeated calls for press freedom.

THE JOURNALISTS HARRASSED DURING THE PROTEST

Bernard Akede: On Wednesday, Akede, a reporter with News Central Television, was interrupted and harassed by police officers during a live broadcast at the Lekki Toll Gate in Lagos.

Advertisement

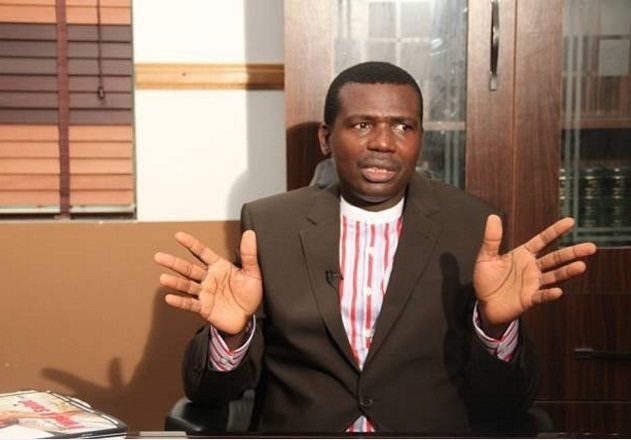

Jide Oyekunle: On Thursday, Oyekunle, chairman of the Nigerian Union of Journalists (NUJ), was reportedly harassed by police operatives while covering the protest at Eagle Square in Abuja.

In an interview, Oyekunle said Beneth Igwe, commissioner of police in the federal capital territory (FCT), ordered the officers to arrest journalists.

“I was coming from the national stadium, and upon getting there, the FCT commissioner of police, Beneath Igwe, asked the police to arrest journalists,” he said.

“Since I didn’t commit any crime, I was covering the protest, and he asked them to arrest me, and he collected my phone, which is still with him.

Advertisement

“It took the intervention of other journalists around that called the attention of the other officers that this is the chairman of the Nigerian Union of Journalists and that he should not be taken as he is covering protests.

“I don’t know why the police are trying to suppress press freedom while we are carrying out our constitutional duties. This is unfair.”

In a statement, Josephine Adeh, the FCT police spokesperson, said Oyekunle was taken to a safe location after the police perceived the environment was “unsafe”.

Yakubu Muhammed: The Premium Times reporter was assaulted by police officers in Abuja on Thursday.

Advertisement

Despite wearing a press jacket and having identified himself as a journalist, he was hit with a gun butt and sustained a head injury.

Muhammed’s camera was also damaged.

Advertisement

Kayode Jaiyeola: Also in Abuja, Jaiyeola, a photojournalist with Punch Newspaper, was arrested by a police officer allegedly working with the office of the National Security Adviser.

Jaiyeola was handed over to the FCT police command and was detained.

Advertisement

Mary Adeboye: In the case of Adeboye, a journalist with News Central Television, she was tear-gassed by police officers while covering the protest in Abuja.

Jonathan Ugbal: In Cross River, Jonathan Ugbal, managing editor of Cross River Watch Newspaper, was harassed and arrested at the Mary Slessor roundabout in Calabar, the state capital.

Advertisement

Ugbal was taken to an undisclosed location where he was detained for several hours. He was covering the protest on Thursday.

In Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, nine staff members of Radio Ndarason International (RNA), including the editor-in-chief, head of programs, and Nigeria office director, were all arrested.

The journalists were said to have been arrested on Thursday morning after the Borno commissioner for information and internal security visited the radio station.

The journalists are still in detention at the police headquarters in Maiduguri.

In a statement condemning the attacks on journalists covering the protest, the Centre for Journalism, Innovation and Development (CJID) said at least 29 journalists were assaulted during the demonstration on Thursday.

SUSPECTED ANTI-PROTEST THUGS ATTACK JOURNALISTS IN DELTA, KANO

Young Nigerians, in large numbers, hit the streets of Delta to join the ongoing nationwide demonstration. They also carried the country’s flag and placards with different inscriptions.

While the protest was ongoing, some suspected anti-protest thugs were said to have stormed the popular Inter-Bus roundabout in Asaba, the state capital, and assaulted protesters, including journalists.

Amour Udemude, the state correspondent of The PUNCH Newspaper, started recording the incident, but he was attacked by the thugs, and his phone was seized.

Two other journalists were also assaulted in the process.

According to reports, the police officers at the location did not intervene.

Monday Osayande, a Guardian Newspaper reporter, and Matthew Ochei, a Punch Newspaper journalist, were attacked by “pro-government protesters” while interviewing protesters in the state.

A TVC correspondent was also said to have been attacked by hoodlums and sustained an injury to his hand while reporting on what was happening at the protest grounds in Kano.

At least eleven other journalists working with Channels TV were attacked while in their official vehicle.

Ibrahim Isah, a journalist with TVC, was injured while trying to flee the location of the protest.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND DEMOCRATIC PRACTICE

Press freedom in Nigeria faces significant challenges due to economic constraints, a lack of protection for journalists, and political pressure.

Even though there are laws supporting press freedom in Nigeria, the effectiveness is usually hindered by implementation challenges.

Section 22 of Nigeria’s constitution (1999) provides for the freedom of the press and mandates the media to uphold the responsibility and accountability of the government to the people.

Also, section 39 of the same constitution guarantees the right to freedom of expression and press. It allows individuals to hold opinions, and receive and impart information without “interference”.

The Freedom of Information Act grants journalists access to public records and information, providing a framework for transparency and accountability in governance.

The National Broadcasting Commission Act (1992) regulates broadcasting and supports media freedom by setting standards for the broadcasting industry.

There is also the Nigerian Press Council Act (1992), which upholds ethical standards and resolves complaints against the press.

Despite these laws, protests and elections are usually marred by assaults and harassment of journalists in Nigeria.

Add a comment