BY OLUWOLE OJEWALE AND TOSIN OSASONA

Nigeria has a data problem, a deeply rooted governance problem manifested in poor data quality, fragile data generation infrastructure and blatant politicisation of data. To argue against this fact is to provide an alternative explanation for Nigeria’s disappointing inability to conduct a credible census since 1962, conflicting unemployment figures, selective release of economic data, inaccurate and incomplete health data, discrepancies in school enrollment rates and unreliable criminal justice statistics, among others. Given this context, it is imperative to interrogate recent statistics by the NBS on kidnapping and ransom payments in Nigeria.

There is a concurrence among most scholars in Nigeria that bandits are the various organised criminal groups operating mainly in the Nigerian north-west region. Driven primarily by economic imperatives, these criminal groups have in the last decade indiscriminately attacked rural communities, commuters and security agencies in the region. Undoubtedly, these criminal groups have evolved a sophisticated and strategic approach to kidnapping for ransom, demonstrating tactical proficiency in carrying out abductions, often utilising intelligence networks, exploiting security gaps, and operating in remote areas with challenging terrain.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics’ Crime Experience and Security Perception Report, 2024, Nigeria recorded a total of 2.23 million kidnapping incidents during the year under review, with 63.5 percent of these incidents occurring in the north-west geopolitical zone—highlighting the significant role of bandits in Nigeria’s kidnapping economy. The report indicates that 8.6 percent of households in the north-west reported experiencing kidnapping, compared to a national prevalence rate of 3.2 percent. During the reference period, ₦2.2 trillion was paid as ransom, with 54.5 percent of the payments made in the north-west. Additionally, the average national ransom per incident was ₦2.67 million. The report unequivocally places the north-west as the loci of Nigeria’s kidnapping crisis.

Advertisement

Ideally, an evidence-based report should provide impartial and definitive proof of the facts it presents. However, this presumption depends on the rigor of its methodology and the credibility of its publishers. Additionally, regardless of how the evidence is framed, it should be consistent with logic, widely accepted knowledge, and established facts. The report does make bold and unsettling assertions that require objective evaluation.

The methodological rigour of the report is insufficient relative to the bold claims presented. Beyond its scantiness, the methodology has key deficiencies, the sampling representation is grossly inadequate for regional conclusions that the study made. To start with, the pilot survey was conducted only in Kuje and Bwari area councils in the FCT, using 20 households, raising concerns about the appropriateness of the pilot to reflect regional variations, especially in the north-west, which is reported as the epicentre of kidnapping incidents. Also, the report failed to provide sufficient information on the sampling frame and cluster design. While the sampling frame uses the Housing and Population Census 18,000 Enumeration Areas, it selected 1,020 Enumeration Areas and 12,281 households nationally. Can it be said that this sample size meets the test of sufficiency to validate the ₦2.2 trillion ransom payment?

The methodology section is silent on sampling design specificity such as specific variables used to stratify the enumeration areas, and household selection methods although the report referenced “systematically selected”, but there is a need for more clarity. The section is also silent on the non-response rate, while it mentions non-response adjustment for weighting but doesn’t state the actual non-response rate achieved. This is a critical indicator of survey quality.

Advertisement

There is also the problem of lack of detail on crime definitions and ransom data verification. The methodology is quiet on how “kidnapping” was defined or how ransom payments were verified. Given the sensitive nature of ransom payments, relying solely on household self-reporting may lead to exaggerations or omissions. Ultimately, the study highlights the risks of potential bias with studies reliant on self-reported data. The reason is simple, respondents may either overstate or understate their experiences based on fear, stigma, or misremembering events, impacting the accuracy of the prevalence and ransom figures. The study does not discuss strategies utilized for cross-referencing self-reported data with other sources and address how potential biases were minimized during interviews.

Beyond methodological inadequacies, the study inexplicably contradicts logic and established facts in some of its most critical findings. It is against the grain of media reportage and share of conversation that Nigeria had more than 2.2m kidnapping incidents in one year. The study states that residents of the northwest paid bandits around ₦1.2 trillion in ransom in the period under review. For context, Zamfara and Katsina states are epicentres of kidnapping in the northwest.

Zamfara state budgeted N188.87 billion for 2023, while Katsina had N288bn for the same year. Their combined budget is around a third of the amount the report asserts was paid by the entire region. In interrogating the data; one is bound to ask again; where did the victims of kidnapping in Nigeria’s northwest get 1.2 trillion naira to pay for ransom within 12 months? Given the general knowledge that government is usually the biggest spender in any economy; even if the state governments are the ones paying the ransom; with their meagre budgets; how did the states meet other fiscal obligations? The northwest region is the poorest geopolitical zone in Nigeria, with more than 70% of residents living below the poverty line and in rural communities. This is not an attempt to downplay the plight of the communities experiencing vagaries of violence by bandits.

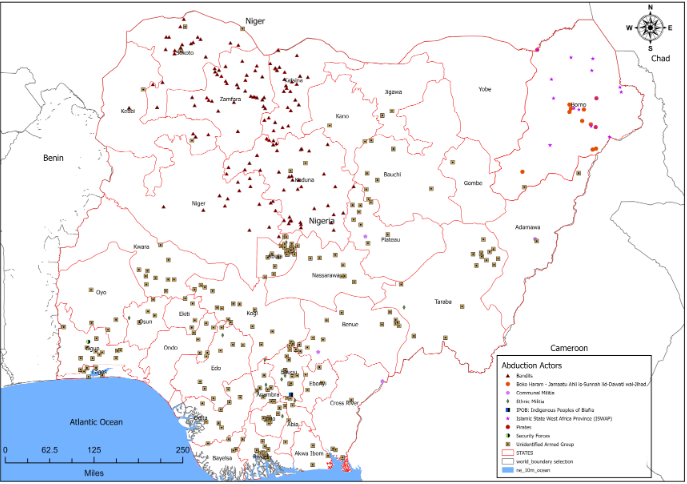

For the purpose of comparison, we checked the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) repository. ACLED is an independent, impartial, international non-profit organisation collecting data on violence in all countries and territories in the world. We extrapolated the abduction data for the period (May 2023 – April 2024) and found 634 incidents across Nigeria (see Figures 1 and 2 below).

Advertisement

The data from ACLED contradicts findings by the NBS estimated at 2,235,954 kidnapping incidents nationally using a perception survey. Given the preponderance of media reports on kidnapping in Nigeria, there is no adult interviewed in Nigeria who will not report that the crime is on the rise. But that does not equate to lived experience.

Just to bring clarity to this figure; 2,235,954 kidnapping incidents would translate to over 4.4 million people if we assume an average of two persons were kidnapped per incident. This perspective becomes pivotal as abductors are often engaged in mass abduction for criminal gains. The population of Gabon in 2023 was estimated to be around 2.4 million people. Did the NBS data managers think about the logistic requirement to kidnap a population twice that of Gabon within 12 months?

How would the abductors manage the transport logistics for such a criminal enterprise within the time frame? We are raising the pertinent questions because empirical data must not go against the logic of common sense. Insecurity is real in Nigeria and we advocate for a whole-of-society approach to address the issues. However, the objective of this piece is to emphasize the importance of aligning statistical reports with on-the-ground realities to foster trust and actionable insights.

Advertisement

Inflated statistics can misinform policy decisions and public opinion. Such data has potential consequences for Nigeria’s security sector, including resource allocation and strategy development. Such figures also have significant implications for Nigeria’s international reputation and investor confidence as they prospect for business across various sectors in the country.

Dr Oluwole Ojewale and Tosin Osasona (security and law scholars) wrote from Dakar and Ibadan respectively.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment