For five days in July 2015, ‘Fisayo Soyombo, editor of TheCable, was in Liberia to report on life in the West African country, on the back of its struggles with Ebola Virus Disease (EVD). But he was hit by a sudden rise in temperature shortly afterwards, fuelling fears he might have been mowed down by the very virus he was trying to cover.

When I started feeling sickly in the morning of July 20, 2015, I panicked. Ordinarily, there is nothing untoward about feeling feverish and running a high temperature. But I had just returned from Liberia, one of the three West African countries where Ebola had killed 11,281 people.

Over the course of five days, I had met dozens of people who had a thing or two to do with the viral disease: doctors, nurses, survivors, gate keepers, cleaners, social health workers. Of note, I spent the bulk of that time at the Renaissance Hospital, famous – or infamous – for being the hospital where Ebola was first confirmed in Liberia. Knowing that a high temperature is the first hint of an impending Ebola crisis, I was very disturbed. Could I possibly be at risk? That can’t be, I murmured to myself that morning. Not after every precaution I took ahead of the trip.

Outside the period of the 2015 general election, Monday July 13 was about my most rigorous day of 2015. It was the day that my doctor, also a friend of nearly two decades, picked to offer me medical advice ahead of a dangerous trip. In addition, it was the day President Muhammadu Buhari chose to sack the service chiefs who worked with Goodluck Jonathan, his predecessor. While my phone ‘may never have rung’ like Reuben Abati’s, I have scant understanding of his groans on being a slave to breaking news. To edit an online paper like TheCable meant news literally dictated the pace of my life, and the danger of the trip meant my appointment with the doctor could never be cancelled.

Advertisement

So, after a seesaw journey consisting of stopping by roadsides to attend to news, I was finally at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) with my doctor-friend, a brilliant, courageous young man who made no effort to discourage me from travelling to Liberia.

“But you must be very careful,” he warned as I made my way out of LUTH. “You have to stick with the plan – studiously.” He had his plan.

AN ALLIANCE WITH WHO

Advertisement

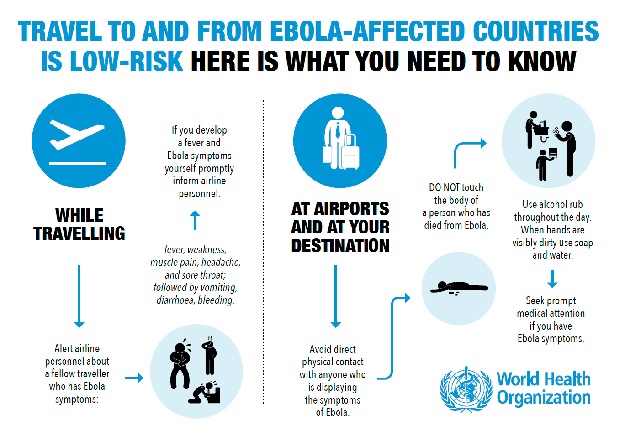

But I had mine, too. In the preceding weekend, I had ransacked the website of the World Health Organisation (WHO) for all its periodic updates on Ebola since its outbreak in March 2014. I knew all the early and late signs of the virus, the various mediums of contracting it, the myths about it, the havoc it had wreaked in Guinea and Sierra Leone as well.

So I had adequate information. My doctor’s plan centred on prevention, mine on symptoms. Armed with information and medical advice, I headed for the Murtala Muhammed International Airport, Lagos, on July 14, satisfied that I had done enough to return as safely as I was leaving. My body temperature on the day was perfect: 37°C.

GHOST COMES CALLING

A week and a half later, I was downcast. Back in Nigeria and after days of fever, I fetched my thermometer (I bought it just before the trip so I could monitor my temperature). It read a frightening 40°C. That was July 24, 2015.

Advertisement

Having departed Nigeria with the perfect body temperature, a three-degree rise could not possibly be natural. Finally, it was time to explore non-temperature signals. I grabbed the mirror and opened my tongue; it lacked the white coating or the furry look or the deep ridge in the middle typical of fresh Ebola victims. I consciously stretched my joints in anticipation of pains (another symptom), but they felt just fine. This can’t be Ebola.

But I remained worried by my high temperature. Ada Igonoh, the First Consultants doctor who contracted (and survived) Ebola from Patrick Sawyer, recorded a temperature of 38.7°C three days after she started evaluating her viral status. Describing her shock on that figure, she would later write: “As I type this, I recall the anxiety I felt that morning. I could not believe what I saw on the thermometer. I ran to my mother’s room and told her. I did not go to work that day. I cautiously started using a separate set of utensils and cups from the ones my family members were using.” The second day, her temperature rose to 39.7°C; and after her blood sample was collected the third day, she was pronounced Ebola-positive.

That was a doctor. Who was a bloody journalist not to be afraid? No longer able to contain my restlessness, I called my doctor, who – to worsen matters – had embarked on a three-month trip to Akwa Ibom state.

“I am very worried, doc,” I said matter-of-factly, with a precision he understood to mean I was in no mood for usual banters. “With a temperature of 40°C days after returning from Liberia, convince me that I haven’t contracted Ebola!” He managed to – because by the end of the conversation, I was prepared to start treating malaria.

Advertisement

But it did little to assuage my fears. Should I turn myself in for a test to ascertain my Ebola status? Yes. But that could trigger the public panic button, and spark fears that the virus had been reintroduced to the country. No; not until there is at least one more symptom? Yet, I didn’t want to be the next ‘Crazy-man Sawyer’ as Jonathan angrily branded the index case in 2014. While that debate raged on in my mind, I bought Lonart DS and tried to reassure myself that I was only dealing with malaria.

The next day, my torment continued. My arrival at the office coincided with a Channels TV broadcast on Ebola. My heart skipped. Did I arrive just in time to learn something that would be useful in treating the virus I just contracted? The previous day, Taiwo Obe (better known as TO), a highly-respected figure in Nigerian journalism circles, had called, and on learning of my Liberia trip, said something like: “I hope you have submitted yourself for quarantine.” So my heart was skipping for the second time in two days.

Advertisement

With Channels TV discussing Ebola and TO’s words reechoing, I raced to my laptop to punch the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) of WHO. A few minutes later, it was Mansur Ibrahim, TheCable’s social media manager, who was knocking on my door. “Editor, see Ebola for Channels TV. You wey just return from Liberia, you dey watch am so?” he joked. He was his happy-go-lucky self. “You even dey read am for computer? Ebola ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo.”

I was tension-soaked.

Advertisement

From the day I returned to Nigeria, I had decided to practise what I called quasi-isolation. But on noticing my temperature rise, I became stricter with it. I cancelled all personal and formal engagements (save one with the facilitator of the trip), and I withdrew into myself. I entertained no single visitor at home, and my popular response to planned visits was that I was “unavailable for the next three weeks”. I kept my sanitizer close still, and I avoided the newsroom. My real difficulty was not how best to isolate myself; it was isolating myself without the notice of people around me, without subjecting anyone else to the kind of fear I was dealing with.

Three days went by and I had completed my malaria treatment. I summoned the courage to re-evaluate my temperature. Rather than fall, it had risen to 40.2°C. That night, I could not sleep. My mind kept wandering back to Liberia, and one by one, I was making mental list of all the people I had contact with, wondering who passed the virus on to me?

Advertisement

Was it Prince, the Ebola survivor who spent time at the Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) and was eventually discharged on his 34th birthday? Prince had contracted the virus from his mother-in-law, a health worker who herself got infected caring for victims. Prince had instructed all other members of the family to steer clear of his mother-in-law’s room, and he was the only one who went in day and night to care for her. After contracting the virus, he “died three times” before finally surviving. His story was touching. But after surviving, he was sacked by his employers and he returned home to face rejection by his own people; they believed – in error, of course, – that he could still infect them with the virus. I wanted to show Prince some kind of support, so I hugged him after the interview. Was that how I contracted it?

Or was it from Josephine Karwah, who was five months pregnant when Ebola came calling, but clung on to her life to become one of only three pregnant women to pull off the feat in the whole of Liberia. Was it from the nurses that I spoke with at the ETU? Regardless of who it was, I must have a doctor examine me tomorrow. Perhaps it was even typhoid and not Ebola. Still, it had to be a doctor I could trust; someone I’d met before.

A DOCTOR WITHOUT DOCTRINE

At the break of dawn, I had a WhatsApp chat with a private doctor I met last year. He had needed to run tests for a patient at Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH), but the hospital vehicle was unavailable. Patient was terribly sick and none of her family was available. I offered to help, driving both patient and doctor to LASUTH, and back to the private doctor’s hospital. You have a good reputation with him, so why not! Explain you just treated malaria, first. Get tested, and take it from there.

Rather than fix an appointment to examine me, doctor sent a message saying my ill-health was a case of “drug resistance or unresolved malaria”. He incredibly had solutions ready before even getting a hang of the problem!

“Let’s see by 7pm,” he wrote. “Am going to place you on daily injections (three days) and some very good oral medication (five three days. All will be ok. Just come along with 8k.”

I bolted.

Instead, on August 2, I mustered all the strength in me to walk into a hospital for tests. Within an hour, I had my result ready, anxiously waiting for a doctor to interpret the jargon on the sheet. The doctor, a heavily-bearded man, could pass for a religious figure save that he rocked secular, nightclub-style music on his phone.

As though he had the gift of clairvoyance and had seen my worries, he had an unruffled mien and flung out his words rather dismissively: “You have absolutely nothing to worry about because your figures are okay. What you feel are just the aftereffects of the malaria you just treated. They will continue for a week and a half. Just drink a lot of water and have a lot of rest. You will be fine.”

“So, I need nothing? Injection? Drugs?”

“Nothing.”

Those words were consoling. But that relief was inferior to the joy I felt on August 8 – 21 days after leaving Liberia and the full cycle for the expression of an Ebola infection – when my temperature read 37.6°C. I hadn’t contracted Ebola, after all; I was only being haunted by its ghost – the psychological hangover of keeping the company of people whose lives had been virtually ruined by the virus.

With the ghost of Ebola now ostracised, I can set about the very important task of telling the stories of Liberian Ebola survivors, who left ETU sated with joy only to discover that their plunge into misery had actually just begun.

8 comments

Lol. Amazing read. Thank God, that you, my friend, are well and I can hug you without worries!

Just now

lol. very true was just the mind going overboard as a result of the information its received.

hmm all ye journalists… I’m very happy for you though.

Nice write up there. Keep it up.

Honestly at some point, I felt scared too. I noticed the traces of fear in you but was saying silent prayers. Thank God for taking you there and bringing you back intact.

Fisayo….I so much admaire your style of writing, powerfully descritive and I can imagine the anxaiety you left and the extent of relief that would have come your way when you finally learnt from the expert, everything was good.

Hmmmm! I no envy you at all o. See how I nearly die of fear silently last year as I was away on vacation. My problem was that I had flown out through the same airport Sawyer came in through and my mind started imagining things. I finally released myself after three weeks. The thing no easy o.

You probably didn’t even have malaria; you probably suffered Medical Scool Syndrome, a situation where young medical students begin to manifest the symptoms of a disease they had to deal with, that traumatized them!

Hmm I can imagine how u feel

Is not easy at all.

Praise God for you.