BY DAVID BASSEY ANTIA

Nigeria has long enthroned itself as a theatrical stage for dramatic political spectacles, an endless show of acrobatic governance that often put the people’s interest at farsight, turning legislation into a mockery of hungry, weary citizens.

The masses watch with forced laughter; others bemoan the absurdity, concluding that we had long fallen off the cliff of hope for genuine democratic progress. But there is yet another segment of the population—those who cannot even afford the time to watch the unfolding farce, as they wrestle with survival beneath the threshold of dignified existence, day to day.

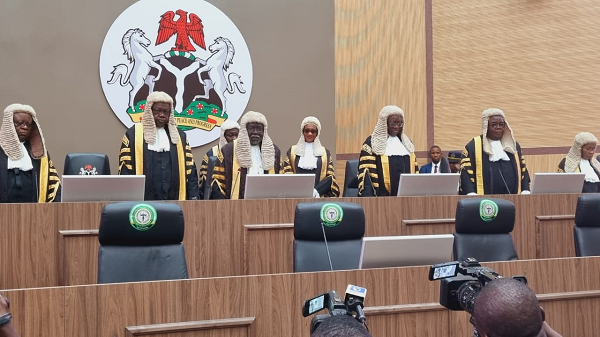

Still, Nigerians hope—not in the immediate palliative illusions that the executive or legislature may pretend to conjure, but in the quiet strength of the judiciary, the third estate in the realm, and presumed last beacon of justice. Hence the enduring maxim: the judiciary is the last hope of the common man.

Advertisement

But we must now confront a pressing question—what remains of this “last hope” in the present context, where court judgments are treated with governmental indifference if not outright disdain? And if we dare to probe further: what becomes of a people when even this final hope is eroded? How long shall Nigerians continue to wait and wail upon a tardy hope that appears to recede farther with every flicker of vision?

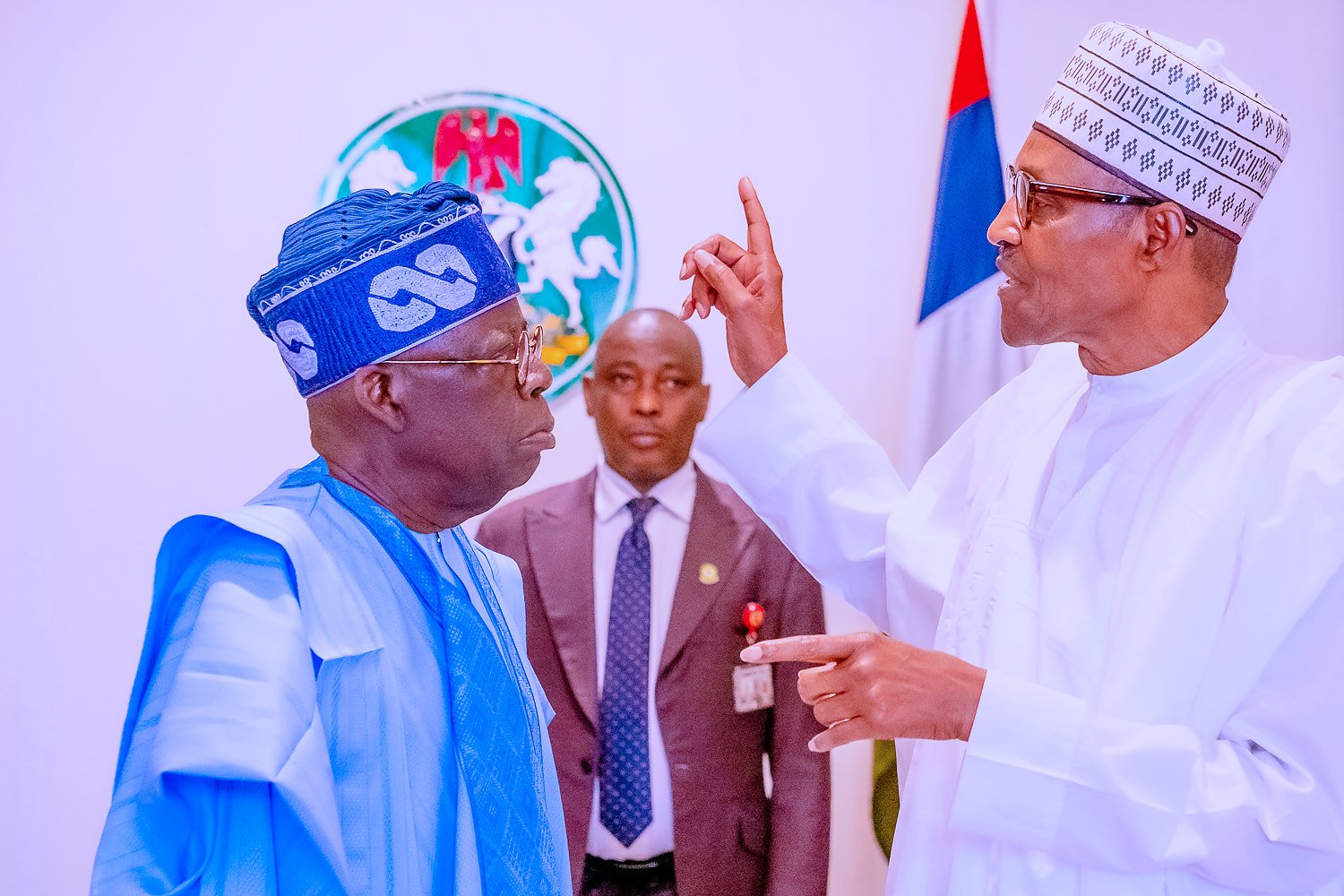

Rivers state has been the stage of an evolving drama in the past two years, particularly following the emergence of Governor Siminalayi Fubara. In its recent pronouncement, the Supreme Court of Nigeria condemned as gross misconduct the diversion of local government allocations and chastised state governors for the unlawful dissolution of democratically elected councils and their replacement with caretaker committees or whatever name they may be styled with. The court was categorical: caretaker committees are unconstitutional, and any local government administered by them is not entitled to receive federal allocation.

Yet, despite this clear directive, the Rivers state sole administrator, Vice Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas (Rtd.), has appointed administrators across all 23 local government areas in defiance of the ruling. Even more disturbing, the federal government has disbursed the allocations to these illegally constituted councils.

Advertisement

This situation raises a deeply unsettling question: Is Rivers state still operating under the nourishing canopy of constitutional governance, or has it become a whimsical appendage of executive impunity? What version of the constitution is at play in Rivers state?

According to Lord Coke in Miscellaneous Offences Tribunal v. Okoroafor (2001) 10 NWLR (Pt. 745) 310, the rule of law requires that governmental powers operate within defined legal boundaries, with discretion tightly constrained by enduring principles. Coke famously described the rule of law as “a golden and straight cord of law, as opposed to the uncertain and crooked cord of discretion.”

Section 287(1) of the 1999 Constitution clearly mandates that “The decisions of the Supreme Court shall be enforced in any part of the Federation by all authorities and persons, and by courts with subordinate jurisdiction to that of the Supreme Court.” Thus, the actions of the Rivers state sole administrator amount to nothing short of a flagrant and contemptuous disregard for the Supreme Court’s judgment.

In Falola v. UBN PLC (2005) LPELR-15506, the supreme court defined a “judgment” as a binding and conclusive determination in a dispute between parties. Therefore, a valid and subsisting court order must be obeyed without qualification. It is unconstitutional, and I dare say criminal, to disobey such orders. In Oko-Osi v. Akindele (2013) LPELR-20353 (CA), it was declared that obedience to court orders cements the rule of law and preserves social harmony, while disobedience amounts to a deliberate subversion of peace and order in society.

Advertisement

The supreme court, in UBA Plc v. Jargaba (2007) LPELR-3399 (SC), emphasized that court orders are not idle declarations; they do not exist in a vacuum. The enforcement of judicial orders is foundational to the administration of justice and the very soul of the judiciary.

This leads to the lingering constitutional dilemma: can any authority—state or federal—amend or circumvent a decision of the supreme court? The answer lies squarely within the architecture of the constitution.

The supreme court, as the apex judicial authority under Section 230(1) of the 1999 Constitution, occupies the pinnacle of Nigeria’s judicial hierarchy. Section 235 of the same constitution forecloses any form of appeal or review of its decisions by another body. Its judgments are final and binding in all respects. Justice Chukwudifu Oputa, JSC (of blessed memory), captured this judicial finality with characteristic eloquence in Adegoke Motors Ltd v. Adesanya (1989) 13 NWLR (Pt. 109) 250 when he said, “We are final not because we are infallible; we are infallible because we are final.”

Yet, in Rivers state, the finality of the supreme court’s decision seems to have been reduced to a rhetorical footnote—ignored and mocked by those entrusted with upholding it. This signals not merely defiance, but a dangerous descent into executive lawlessness, a brazen invitation to constitutional anarchy.

Advertisement

The rule of law, upon which any genuine democracy is anchored, becomes a mirage when the president or any authority treats judicial orders as optional. In a constitutional democracy, the willful disregard of court judgments is not just unlawful—it is treason against the constitution. It signals the demise of democratic governance.

The sole administrator of Rivers state—and indeed the federal government—must be reminded, unequivocally, that the authority of the judiciary is not ornamental. It is substantive. It is final. It is binding. Disobedience to the supreme court’s order is a constitutional transgression with dire implications.

Advertisement

Let all who wield power take heed: The judgment of the supreme court is not a suggestion. It is the law. And in a democracy, the law is not negotiable.

David Bassey Antia, president of the Council of Topfaith University Students, can be contacted via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.