Clad in vibrant attires, many went to church in a festive mood. It was Pentecost Sunday, and the parishioners looked forward to the celebration that lay ahead – or so they thought. When the service was abruptly cut short by gunshots from savants of mayhem, it dawned on them that tragedy had also been lying in wait alongside the promise of fanfare. Chaos reigned supreme at St Francis Church Owo, Ondo state, south-west Nigeria, for at least an hour, on June 5, 2022. Across the town, residents took cover; doors, windows and gates were slammed shut, market wares were hurriedly abandoned and the streets soon became empty.

When Rotimi Akeredolu, governor of the state, visited the town – where he hails from – tears flowed freely as he was bombarded with tale after tale of tragedy, despair and bravery in the face of death. It has been 17 months since the incident, but the memory lingers in the minds of residents, as evidenced by their cautious disposition towards, and engagement with, outsiders.

This is the tale of those ‘left behind’ by their loved ones who were forced to embark on an infinite journey they desired not.

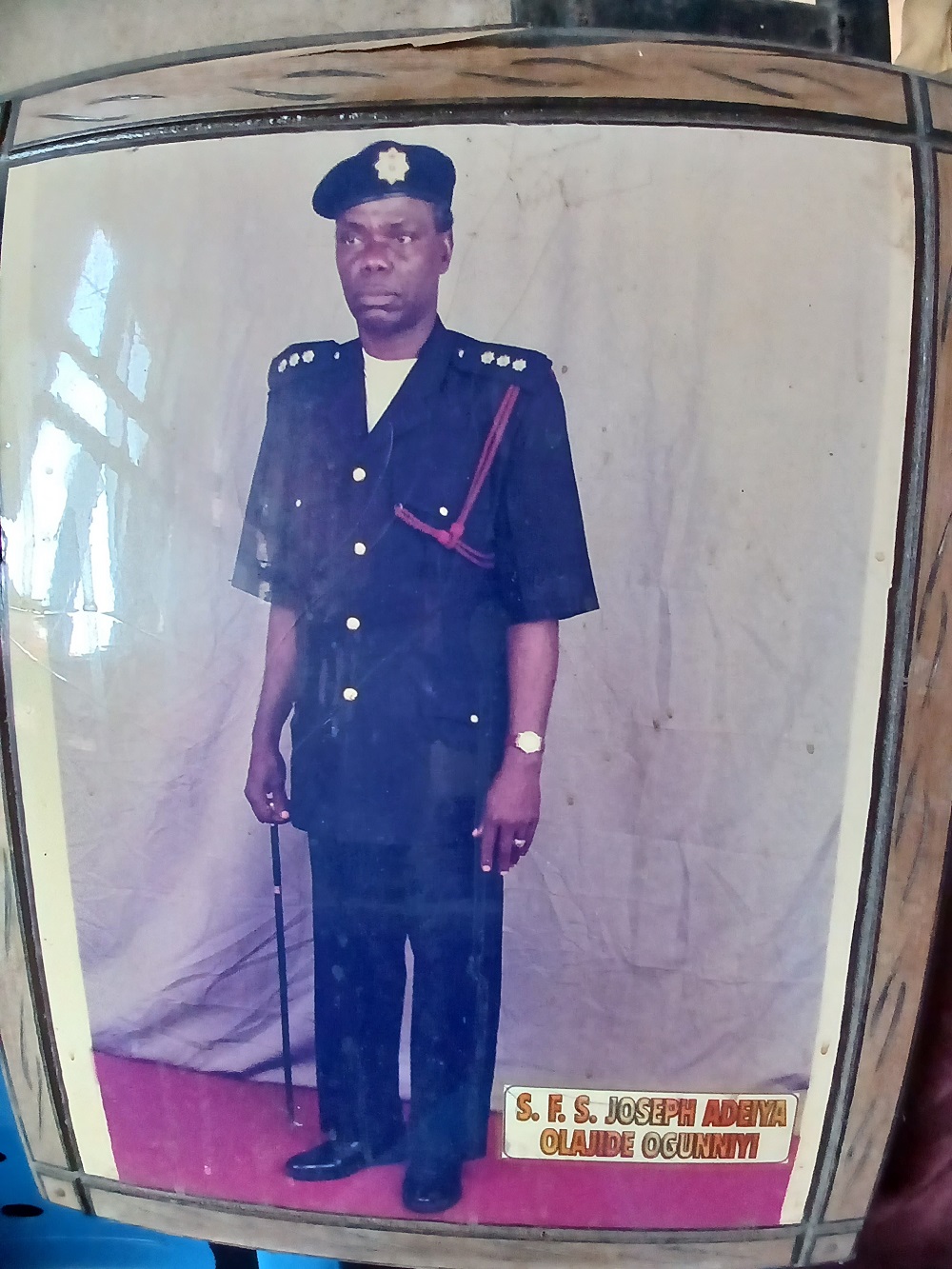

THE FIREFIGHTER UNABLE TO FIGHT FOR HIS WIFE

Advertisement

If fate did not dance to its tune, Joseph Olajide would be dead. But the ways of fate are mysterious, so the octogenarian lives on, albeit a life filled with encumbrances, grief and discomfort.

Olajide, 88, was meant to be in church when the armed bandits invaded. But as he and his wife prepared to head out that morning, he experienced pain in his back and decided to rest for a bit, pending when his aching frame would permit him to make the trip.

His wife, who proceeded to church without him, never made it back home. She was among the 40 persons – mainly women and children – killed in the attack that shook the nation, the Christian community and the Catholic Church.

Advertisement

“She was the wife of my youth,” Olajide said as we settled down to take a trip down a memory lane paved with heartache and dotted with long pauses. He was seated in the centre of the living room of his family house, forsaking the patterned weathered couch for a sky-blue plastic chair.

Surrounded by relics of days of yore, we met him all alone in the unpainted apartment, gazing out through the open window as the horns of cars and motorcycles – aided by the chatter of youths from the verandah – dwarfed the silence and stillness in his abode.

Recounting the day his wife died, he said: “After I had my bath, I started to put on my underwear when I heard a sound around my waist, it was almost as if I was hit with a stick. I cried out and a young man came in. I asked him to help me boil water and massage my back. After the massage, I decided to lie down because I could not handle the rigour of incessantly standing and kneeling in church. Shortly after, I slept off.

“I did not know when my wife left the house. I was jolted from sleep when I heard someone shouting ‘baba, baba’. I asked what was wrong and the person said ‘there has been a tragedy’.”

Advertisement

When Olajide eventually made his way to church, he learned that his wife’s body had been taken to the mortuary at the Federal Medical Hospital in Owo.

“If not for my back pain, I would be dead like my wife,” he said.

Olajide, whose sitting position in the church was one of the places first attacked, buried his wife in front of their nearly-completed bungalow. Nowadays, he hardly frequents the property, preferring to remain in the family house.

“My wife had escaped, but she did not wait for the bandits to fully exit the premises. She did not know some were still around. As she tried to walk out of the church, she was gunned down,” he said, stopping abruptly and slipping back into silence as he often did.

Advertisement

Olajide spends his mornings deep in reflection, afternoons in the company of neighbourhood children who troop in to play, and evenings reading the Holy Rosary before eventually drifting off to sleep. The vibrancy his late wife brought to his life has long departed, leaving behind a predictable routine existence.

“I have accepted my fate,” he said, adding that “my two youngest children who are in school sometimes come home when on holiday”.

Advertisement

Olajide was recently hospitalised for 17 days after his back pain resurfaced.

“My bones are not strong again. I was asked to report for observation every two weeks. I have gone back at least four times and I should be there today or tomorrow. But I have no money. My injection is expensive,” he said, stopping again, this time staring down at his clasped fingers which were dancing to the tune of old age.

Advertisement

A former firefighter in the Federal Fire Service, Olajide has seven children with his late wife whom he wedded in 1967. Retired now for over 11 years, he survives on his lean pension from which he also lends support to his two children who are still in the university.

“At this stage of my life, all I need is to eat, get medical treatment, and any kind of support to manage myself,” he said. “I am hardly able to walk. If I walk for a few metres, I get exhausted. At church, I am often on my seat. I can hardly stand for five minutes.”

Advertisement

THE MONOGBE FAMILY TRAGEDY

Three members of the Monogbe family died in the attack; a girl in her late teens, a policeman, and Adenike Testimony, the daughter of 48-year-old Aderonke Monogbe.

Aderonke had just one child who would have celebrated her 12th birthday in September 2023, if her life was not cut short over a year prior — before it could fully lift off.

“The Father had said the grace and was about to end the service when we heard a commotion just outside the church and the gunmen shouted that ‘everybody should lie down’,” the single mother said, her voice unsteady.

Fighting off tears, albeit unsuccessfully, Aderonke continued: “During the attack, everyone was on the floor. I kept beckoning my daughter not to raise her body to avoid being hit by the bullets. When the bandits were done, I ran over to where she was and noticed that almost everyone around her was dead.”

Alive at the time, her daughter said, “mummy, I think the bullet hit my leg”. Given the state of others around Adenike Testimony, rather than worry, Aderonke said she heaved a sigh of relief and muttered a prayer of gratitude.

But her relief would be short-lived.

“Not long after she said those words, my daughter became almost lifeless. Some first responders took her from me and put her on a motorcycle for an onward journey to the hospital. I tried to chase down the motorcycle on foot, but I could not,” Aderonke said.

And so she began the search for her daughter at different hospitals but to no avail. On her way back from one of the hospitals, she put a call through to her brother but one of his children answered the call and blurted out: “My daddy was also killed in church.”

For over 24 hours, Aderonke tried to track down Adenike Testimony but her family members kept assuring her that her daughter was all right. She was told the girl was being administered oxygen at the hospital and should not be disturbed. It wasn’t until the second day that she was informed of the true state of things. In many parts of Yoruba land, south-west Nigeria, bereaved parents are not allowed to be present for their children’s funeral, a tradition which means the last memory Aderonke has of her daughter was when she found her in the throes of agony and on the cusp of death after the attackers concluded their operation.

“When I woke up yesterday and remembered that it was her birthday, I could not stop crying. I was that way until I got tired of crying and decided to say a prayer for her,” she said, turning to look away almost as if the sympathy of onlookers would launch another round of tears.

Aderonke – who does petty trading in a containerised shop paid for by the church and the state government – no longer attends St Francis. To avoid dealing with the memory of the morning her daughter was killed, she moved to St Davids where she now worships.

“There is no way I would go to St Francis and would not feel sorrow every time. I don’t have the mental and emotional capacity yet,” she said.

During the first anniversary of the attack, Aderonke was physically “forced to enter the premises” because she was unable to walk inside when she got to the gate of the church.

“When I lost my daughter, I told myself that I would leave the Catholic Church altogether even though I was born there. But I eventually changed my mind because it is a church I love,” she said.

Oluwasikemi Alalade, a psychiatrist at the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital in Lagos, said Aderonke might be dealing with post-traumatic disorder, given her ordeal.

“Aside from the anxiety symptoms she would be experiencing, the features of PTSD she has verbalised are avoidance (changing church), re-experiencing of numbness (unable to walk in),” Alalade said.

“It’s called re-experiencing because it is a repeat of what has happened before. These are her reasons for leaving the church.”

Aderonke said she has never received professional support from a psychiatrist to deal with the trauma, a development which Alalade insists is pertinent for her to move forward.

“She would benefit largely from psychotherapy to help her work through the PTSD with emphasis on her exposure back to the church and better coping mechanisms instead of avoidance,” the doctor said.

WIDOWED AT 38, FENDING FOR FOUR

For Imisioluwa, widowhood means she now has to work twice as hard and worry more than normal. Her late husband, Ayodele John Monogbe, was a police officer and the brother of Aderonke.

“Before my husband died, he was planning to build a shop for me. If not for God, the church’s support and helpers, I probably may be begging for alms by now,” Imisioluwa said.

“The church gave two of my children scholarships which will last for five years. There’s no day I don’t miss my husband. He was like my mother and father.”

She was neck-deep in the processing of cassava in a makeshift shed built in front of her house when we came calling. Her face was partly covered in white, and so were the faces of the little children running around the compound. Inside, Imisioluwa appeared eager to delve into the conversation but with her toddler fussing relentlessly and desperate for attention, she could not seamlessly verbalise her train of thoughts. After repeated failures, she called on her older son to momentarily hold on to the child. As soon as the toddler was taken away, he protested with a loud cry and after a few seconds of unsuccessful petting by his brother, the consensus was to return to the status quo.

So we settled for the fussing – and began to talk.

“During the attack, my sister-in-law – Aderonke – rushed to remove my last child from the back of her 18-year-old sibling after the latter had been gunned down. After she retrieved my baby, she laid face down and shielded her,” she said.

While the melee ensued, Imisioluwa said she raised her head and made facial contact with one of the attackers, who she quoted as saying: “All of you will die today.”

Unperturbed by her fussy toddler, she continued: “After the bandits left, I found out that my husband and his sister were dead. But Testimony was still alive and she was rushed to the hospital.

“If I had money, I would have sued the hospital because I learned that she was not given immediate attention.

“Testimony was living with me at the time of her death.”

All three Monogbe family members killed in the attack, she said, were buried in her compound with their graves dug side by side and bereft of tombstones.

HOW SAMUEL ‘NARROWLY’ SURVIVED

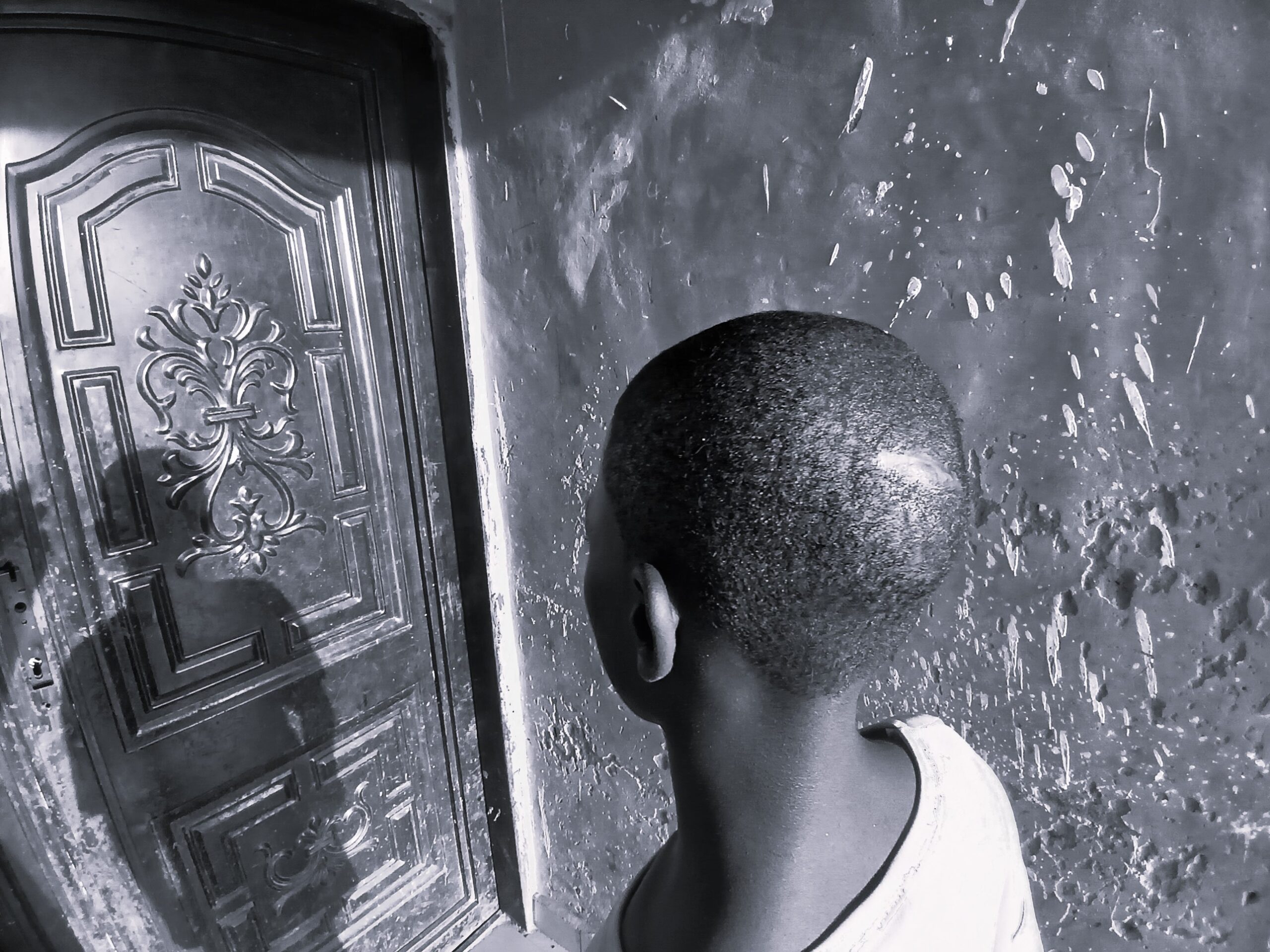

At 11, Samuel Monogbe, Imisioluwa’s son, already has a battle scar — literally and figuratively.

He was shot during the attack, but the bullet only grazed his head. The scar, etched at the back of his head, is unmissable, defiantly warding off the strands of hair that are slowly encroaching.

Everyone in the neighbourhood knows Samuel as “the boy who was shot in the head but survived”. The key detail of the bullet not penetrating is often left out, seeing as it takes away from the dramatic effect of the story.

“As the service was ending, I went to buy ice cream with my elder brother. As I got back to the church, we heard the sound of gunshots from outside, and everybody ran helter-skelter,” he said.

“While we were running, my father tried to check what was going on and he was shot dead.”

To evade detection, the boy said he kept on “running in circles” inside the church’s compound. It was while he was fleeing for safety that the bullet grazed his head. Although Samuel initially hid under a vehicle, he soon noticed that he was bleeding profusely, so he decided to hide behind a nearby toilet to avoid being given away by his flowing blood.

“While behind the toilet, I noticed that people were jumping over the fence, so I joined them. When I landed on the other side, I begged for water from the people around the house where I ran to, but they said I must not drink water,” he said.

“My face was covered in blood and I was disoriented.”

Samuel insists that he was helped to the hospital by his “father” even though his father had been gunned down in the church before he managed to escape. Despite contrary accounts from persons at the hospital where he was treated for gunshot wounds, the 11-year-old said his “father” put him on a motorcycle and drove him to the hospital where he was dropped off.

“To me, the person who helped me to the hospital was my father; he even wore the same clothes my father wore that Sunday,” the boy said.

Commenting on the situation, Alalade, a Lagos-based psychiatrist, said a “post-traumatic confusional state characterised by brief alterations of consciousness” could be a possible explanation for Samuel’s belief that his father – who was already deceased at the time – rescued him.

“In this state, consciousness for some external events is still preserved which may lead to misinterpretation of perception, impaired attention and memory, disorientation and even confabulation,” she said.

Tiwatayo Lasebikan, a consultant psychiatrist, said Samuel may have had a stress-induced hallucination, hence his account of events.

“This type of hallucination is induced by extreme stress and requires no treatment. They are short-lived and the person will be otherwise fine. It could also be a dissociative phenomenon. Dissociation occurs when our brain doesn’t want to accept some reality and it somehow presents us with a different reality,” he said.

“This could also be an issue of defence mechanism or a simple misidentification.”

PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF VIOLENCE, LOSS

According to the World Health Organisation, persons who have been exposed to trauma or loss should immediately be given psychological first aid, and stress management support.

But the psychological intervention does not end there.

“In addition, referral for advanced treatments such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) or a new technique called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) should be considered for people suffering from PTSD. These techniques help people reduce vivid, unwanted, repeated recollections of traumatic events,” the WHO said in its guidance on mental healthcare after trauma.

Olajide, Aderonke, Imisioluwa and Samuel said they have not received any psychosocial support to deal with the potential mental health consequences of their ordeal.

Suggesting possible interventions, Alalade said after experiencing traumatic events, “people need a psychological intervention to prevent the worsening of any of their symptoms and to promote recovery”.

Lasebikan added that victims should be provided physical and psychological assistance “as quickly as possible” because the ripple effects of such experiences can manifest in the “short, medium or long term”.

“For instance, in the short term or immediate post-event, they can experience what we call acute stress reaction. The person can be dazed with everything looking and feeling unreal. They become fearful and anxious. This is usually corresponding to the intensity of the terror.

“In the medium term, some people can develop full-blown depression or anxiety disorder. Some people develop adjustment problems and even there can be persistent personality change after such a catastrophic event.

“In the long term, post-traumatic stress disorder can occur, children can develop conduct problems and some people even develop psychosis.”

Father Michael Abugan, the parish priest of St Francis, however, said immediately after the incident, the WHO sent experts to meet those “who were traumatised in the attack”.

“They moved from house to house to counsel them and I think this was done one or two times; that is for the WHO,” he said.

Abugan said the church also organised “psychological intervention” through seminars facilitated by experts, adding that it is a continuous exercise with the next instalment slated for November.

“It is not going to stop, we will continue to make interventions,” he said.

“So, we are trying to work on this, we will not just rest, we will be empowering them. We will not rest because man is a psychosomatic being. As you take care of the body, you also take care of the mind.”

Add a comment