Photo Caption: Aerial view shows Shell's oil and gas terminal on Bonny Island in Niger Delta. Credit: Sodiq Adelakun / iStock

BY FERMIN KOOP, MICHAEL BUCHSBAUM AND SAMUEL AJALA

Much worse for the climate than carbon dioxide, despite global efforts to control methane, emissions continue soaring. With over a third stemming from fossil fuels production and operation, oil majors – led by Shell – publicly claim to be reducing their methane pollution, but scientists, experts and watchdogs warn that industry data reporting is very misleading.

Despite years of awareness about the climate crisis, greenhouse gas levels continue to soar. Historically, much of the focus has been on carbon dioxide; however, it is now clear that a rapid and sustained reduction in methane is also key to limiting global warming. Methane, with over 80 times the heat-trapping potential of carbon dioxide over 20 years, has contributed to over 30% of global temperature rise since the Industrial Revolution, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Unlike carbon dioxide, which is a wasteful by-product of human activities, a stream of methane is a sought-after gas, a product of fracking and other gas-extraction methods.

In that sense, allowing methane to be leaked or vented would seem a waste of potential profits. Nevertheless, the energy sector alone is responsible for about 40% of all methane emissions, an estimated 80 million tons per year.

Advertisement

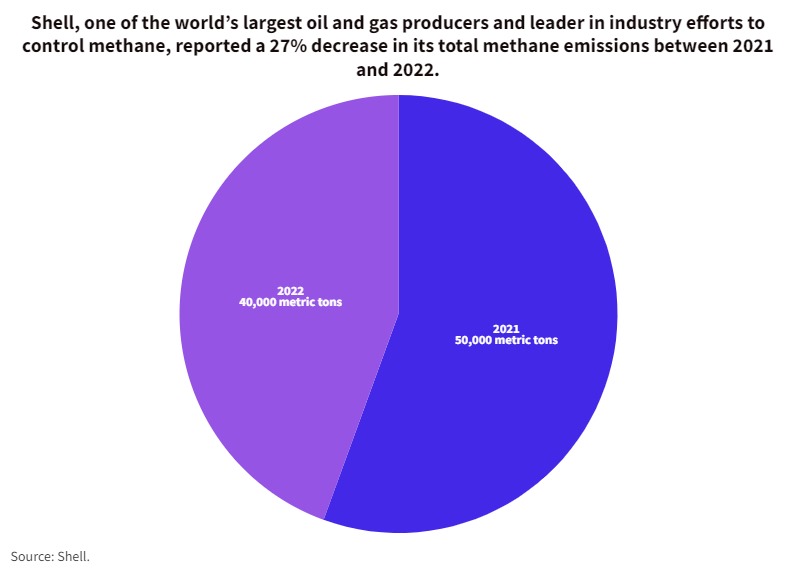

In the case of Shell, one of the world’s largest oil and gas producers and leader in industry efforts to control methane, the company reported a decrease in total methane emissions from its operations from 50,000 metric tons in 2021 to 40,000 metric tons in 2022, a 27% reduction. It also claims to have met its target to keep methane emissions intensity below 0.2%.

However, the way fossil giants calculate their emissions is flawed. Currently, only a small number of producers regularly take field measurements and do routine maintenance on equipment to determine leakages or other accidental emissions.

Advertisement

Sector-wide there’s virtually “no direct measurement happening at oil and gas extraction sites or infrastructure, including pipelines,” said Dominic Watson, a methane expert at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Watson said that oil and gas producers have generally been self-reporting their methane emissions for decades. They have also been setting pollution targets in whatever ways “they saw fit for their sustainability reports, using whatever metrics, baselines and target years they wanted to,” he said.

EVERYWHERE WE GO, WE FIND METHANE

As power plants and industrial facilities have been rapidly shifting away from burning dirty coal towards cleaner natural gas, “fugitive” methane escaping all along the oil and gas value chain has been significantly underreported – even in jurisdictions where regulators are supposedly paying attention.

Advertisement

In 2018, a pivotal study of oil and gas facilities in the United States found that rates of methane pollution were more than 60% worse than what the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was then estimating.

Researchers found that over 2.3% of all produced methane was simply venting into the atmosphere.

In early 2023, Clean Air Task Force released a report visually documenting widespread methane pollution venting from 430 European oil and gas sites over two years.

“Almost everywhere we go, we find methane,” said Theophile Humann-Guilleminot, a certified thermographer at the nonprofit. “Up and down the value chain, there is dangerous methane pollution coming out of Europe’s oil and gas network.”

Advertisement

Even “very small methane leakage rates from gas systems rival coal’s greenhouse gas emissions,” said Debbie Gordon, senior principal of RMI’s Climate Intelligence Program.

SHELL’S ROLE IN METHANE EMISSIONS

Advertisement

Shell is now the world’s 5th largest oil producer by volume and fifth largest oil and gas super major by revenue with ongoing exploration, production, refining and chemical operations spread across 70 countries. The company’s profits soared to $40 billion in 2022, almost double the amount reported in 2021.

Aware of the industry’s growing methane problem, in 2018, Shell made headlines by announcing their intent to lead the sector’s efforts to control leakage. The company vowed to keep methane emissions intensity below 0.2% by using advanced equipment to detect and repair methane leaks and replace older equipment.

Advertisement

Other companies then followed with similar targets, leading to industry initiatives such as the United Nations Environmental Programme Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (OGMP) in 2020. It’s the world’s only attempt to set a comprehensive measurement-based reporting framework, covering all material sources of methane emissions from both operated and non-operated assets in the oil and gas sector. Over 100 companies have already signed up.

In the OGMP’s 2022 report, Shell’s efforts yielded the awarding of a Gold Standard label – the OGMP’s highest rating.

Advertisement

For Shell and the rest of the industry to curtain emissions, operators need to both understand where accidental emissions are escaping from, as well as end the practice of deliberately “liberating” methane during routine venting operations. Unintentional methane leaks can flow from malfunctioning valves, compressors and storage tanks, which often are designed to vent methane when pressures build.

Studies conducted by the IEA found that more than 70% of emissions can be abated using existing technologies and that about 40% of current emissions can be avoided with measures that would come at virtually no net cost.

How oil majors address methane emissions at their owned and operated assets compared to their non-operated assets also varies dramatically. Shell and others “make a lot of public-facing statements that say they are addressing the issue, but significant equity is placed in non-operated assets for which they do not report and have not made any commitments towards cleaning up,” said James Turrito, director of Global Campaigns at CATF.

“To date, we have not seen as many [national oil companies] attempt to really tackle the methane issue. There are reasons for this and barriers that go beyond simply being bad actors,” Turrito said.

SHELL’S ONGOING METHANE STAIN IN NIGERIA

“25 years after Shell left Ogoniland in Nigeria, it continues to ooze oil from wellheads and pipelines into the Niger Delta,” said Avena Jacklin from Friends of the Earth South Africa. As it reduces its climate commitments, Shell “continues to extract massive profits from countries in the South…increases in methane emissions, and contamination of our critical water supplies from Shell’s operations will exacerbate the climate crisis,” she said.

According to the World Bank’s 2020 Global Gas Flaring Tracker, Nigeria is the seventh-largest gas-flaring country globally. But a 2022 World Bank report shows Nigeria contributed most to the overall global reduction, reducing its flare volumes by 1.3 bcm in 2022, a 20% reduction from 2021 levels. Shell joined the Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialization program alongside other producers in support of Nigeria’s goal to achieve zero routine gas flaring by 2035. First launched in 2018, the program was relaunched in 2022.

Shell which helped establish Nigeria’s oil sector in the 1950s, contributes close to 40% of the country’s total oil production and is the largest oil operator. In 2022, Shell Nigeria paid the Nigerian government over $900 million in taxes and royalties.

According to statistics provided by Nigeria’s National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA) and the Gas Flaring Tracker satellite of the World Bank, oil companies throughout the nation, including Shell, have flared about $3.9 billion worth of gas in the last four years.

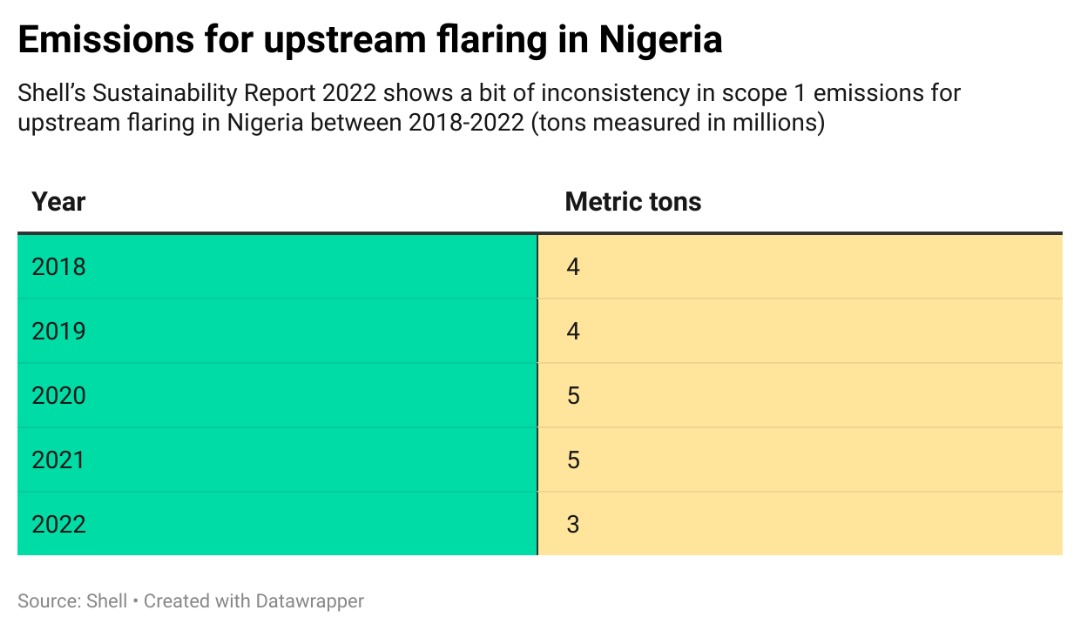

However, Shell’s Sustainability Report 2022, scope 1 emissions for upstream flaring in Nigeria witnessed 2 million metric tons of emissions reduction, with a figure of 3 million metric tonnes in 2022 compared to 5 million metric tonnes in 2021. Their data also shows that between 2018 and 2019, the metric tonnes emissions were pegged at 4 million, respectively. For 2020 it increased to 5 million metric tonnes of emissions.

“They have to explain their data,” said Segun Omidele, President of the Polaseo Group, a Nigerian oil and gas service company and former Shell employee. Given all the many crude thefts throughout the Niger Delta, leading many operators to reduce, shut down or abandon production, “it is difficult to accept there’s been an emissions reduction,” he said.

Dr Ayodele Oni, an oil and gas expert and member of the legal advisory team for Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL), said all identified gas flare points in Nigeria are part of the commercialization program and compliance with it is necessary for companies and producers to get or renew their mining and operating permits. He said reportedly gas flaring in Shell dropped by 80% between 2010 and 2019. Ayodele said this was due to the IOCs’ investment in gas-gathering facilities in Aloma, Adibawa and Otumara.

SEND IN THE SATELLITES

Last year, satellites detected around three million tons of methane from oil and gas operations. The European Space Agency alone tracked dozens of “methane events” from oil and gas operations lasting for more than 15 days across almost 70 countries, according to IEA’s Methane Tracker.

A BBC investigation last year, using World Bank flare-tracking satellite data, identified millions of tons of undeclared emissions from gas flaring at oil fields where Shell, ExxonMobil, and other majors operate.

In 2021, Geofinancial Analytics, a satellite data provider, compared the methane output of fossil fuel companies with their expected emissions level based on self-reported data. Shell and Chevron were the worst performers. The company relies on satellite readings of airborne methane concentrations in North America, Europe and Brazil.

However, the coverage provided by satellites isn’t complete, which means there could be more leaks that are not being accounted for. Existing satellites don’t provide measurements over equatorial regions, offshore operations or northern areas such as Russia’s main oil and gas-producing areas, the IEA said in a report last year.

With help and support from the UN, using a combination of satellite, private and public monitoring methods, the OGMP funds, coordinates and facilitates measurement studies around the world.

There are plans to launch a series of cutting-edge satellites with significantly enhanced resolutions in the coming years. EDF will launch MethaneSat in early 2024, which they argue will be the most advanced methane-tracking satellite in space. Carbon Mapper, a US-based NGO, said it will deploy a complete satellite “constellation” by 2025.

SHELL GAMES

Despite the ongoing climate crisis, Shell continues to develop new oil and gas assets. Since a Dutch high court ordered the company in May to make deeper carbon cuts, Shell has made investments in 10 assets in various countries, including Argentina, Australia, and Brazil.

The company’s share of the oil and gas from these assets, once burned, will result in 325 million metric tonnes of CO2 emissions, campaigners estimate. The company also co-owns more than 750 untapped oil and gas assets which would amount to 4.3 billion metric tonnes of extra CO2; 30 times more than the total emissions from the Netherlands in 2021.

“Every new extraction project Shell approves digs the world into a deeper hole of the climate crisis, and the company’s relatively meagre investments in renewable energy do not make up for that,” Kelly Trout, Research Co-Director at the NGO Oil Change International, said.

This report was supported by Clean Energy Wire grants for cross-border journalism on company climate claims.

Add a comment