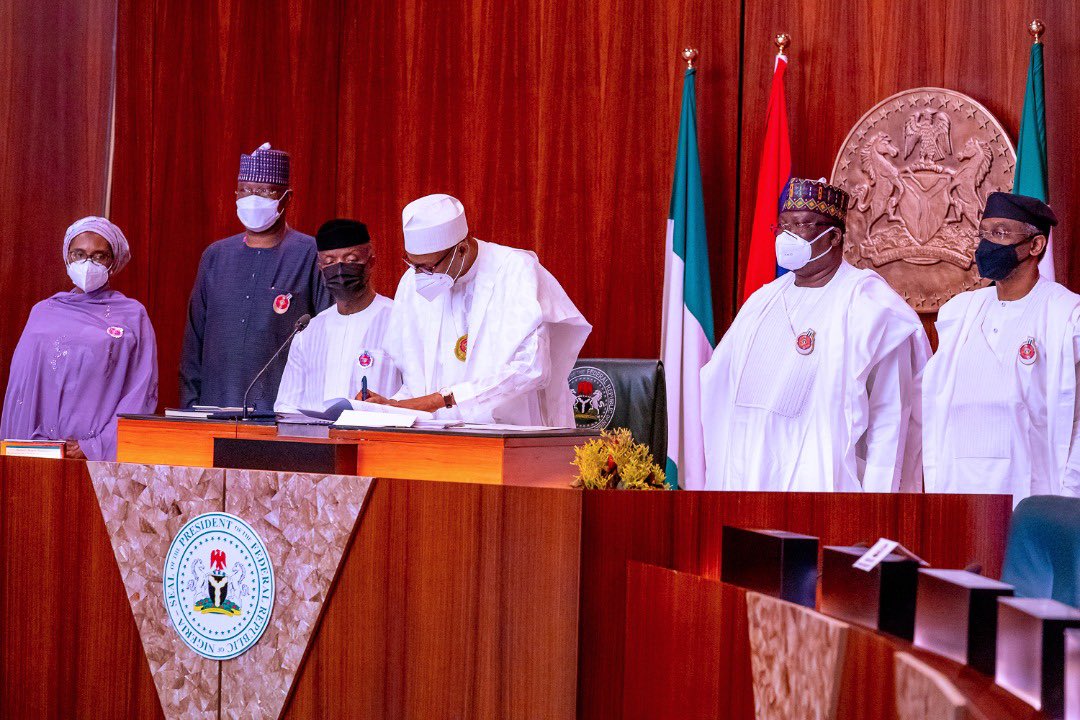

Hadiza Khadijat, female IDP in Karon-Majiji Abuja, sewing a dress for a customer in the camp

BY TITLOPE FADARE

When Liyatu Ayuba arrived at Durumi settlement in Abuja, after fleeing a Boko Haram attack in Gwoza, Borno state, in 2013, she was distraught and filled with despair. She had lost everything with no hope of fending for herself.

Her husband, a former police officer who brought home a major share of the family’s income, was killed by insurgents, leaving her with nine children to cater for.

With no source of livelihood, Liyatu wondered how she would restart her life in an internally displaced persons (IDPs) camp in the federal capital territory (FCT) — miles away from home.

Advertisement

There are over two million displaced people from the north-east region of the country, according to a 2019 report by a UN refugee agency. The insurgency which has lasted over 10 years has left thousands dead and property worth millions of naira destroyed.

Many of the IDPs — including Liyatu — fled the north-east for safety after Boko Haram held sway in a number of towns in Borno and the region at large.

However, Liyatu was determined to survive the hardship inflicted on her as a result of the insurgency. A few months after settling in Abuja, she got an opportunity at a non-governmental organisation (NGO) where she picked up a few skills. She also started a business selling water in sachets.

Advertisement

Until Liyatu fled to Abuja, she had refused to wear the “cloak of dependency”. This could be said about many of the women displaced from their homes owing to the insurgency — some women have taken the bull by the horn.

In this report, five displaced women, mostly widows and living in safer communities in Abuja and Maiduguri, shared how they have been able to take charge of their earnings without waiting for handouts from the government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or individuals.

“Pour water into this bowl. I want to start peeling the potatoes,” Liyatu called out to one of her daughters when this reporter visited her residence, a few meters away from the camp.

While in Gwoza, she ran a restaurant at Muna garage and constantly travelled to Lagos, Republic of Benin, and Ghana for business.

Advertisement

“At the garage, people knew me well because I gave money to people to start their businesses. In fact, I built my house and owned a car. Boko Haram destroyed everything, but I will never give up,” the 50-year-old woman said.

In addition to her cooking business, she produces liquid soap, air freshener, and antiseptic. She also cleans houses, and plaits hair. She uses her gains to settle the house rent and children’s school fees.

“In the beginning, I struggled with getting capital for my business. Now, I make capital and profit. I even add more money to the capital. But I make sure to adjust according to how the market goes,” she said halfway into peeling a potato.

“I have also opened other places where I have people who I pay and they help me with my business in their respective locations. I pay them N500 every day and allow them to eat out of the food.”

Advertisement

Liyatu plays an exemplary role, serving as the woman leader of 18 IDP camps in Abuja. She holds meetings with her counterparts in other camps twice every week, giving them tips on how to manage their businesses even when faced with discrimination.

“If you see me outside, would you think I am an IDP? It is only if you know me before. Some IDPs usually face discrimination because they beg while doing business and dress terribly. Even me, I won’t buy from them if they say they are IDPs and they don’t dress well,” she said, rounding off her peeling.

Advertisement

‘TAILORING, FISH FARMING CATER FOR MY EIGHT CHILDREN’

One striking feature about Khadijat is her effortless smile even while recounting her sad experiences. The 43-year-old, who is also from Gwoza, has been living in Karon-Majiji, an Abuja community along airport road, since 2014.

Advertisement

Her husband was a business mogul back in their community but was killed after an attack by insurgents.

“What happened to us, we don’t pray it happens to anyone. It is not easy,” she shrugged as she recalled the gory incident.

Advertisement

Before the attack that took her husband, Hadiza sold shoes, fabrics, and bags. She was constantly patronised during social events. She and her husband were into fish farming, poultry and they also sold cows and goats.

“On my own, I made thousands of naira in a month because anyone who wanted to marry came to my shop to get things. In fact, my husband used to help me bring fabrics from Adamawa state in his car,” she said.

But her booming trade was abruptly disrupted by the insurgents. Settling in the camp, she started selling akara (fried bean cake) but the business folded up when two of her children became critically ill.

Soon after the illness, she learnt tailoring and recently restarted fish farming to provide for her family.

“Two years ago, a lady brought 75 sewing machines for us, trained us, and gave us certificates. She also opened accounts for us,” she said.

“I charge my customers between N1,000 and N1,500 per cloth because most of them are IDPs. I just started fish farming. Some men come to patronise me. I also do kunu. So far, this is what I use to take care of my children. It is not enough but it can provide for them.”

Kurmi Abubakar is also a widow who arrived in the nation’s capital in 2014 and now lives in Kuchingoro IDP camp.

Before she left Gwoza, she was into fish farming and the sale of clothing items. According to her, she made close to N100,000 daily.

“When I was in my community, I sold clothes — hijab — on a big scale. I also travelled to Cameroon to buy fish to sell in the community. Then, I made a lot of money. In a day, I can make up to N100,000,” she said.

“It was then I had money. In fact, when my daughter was getting married, if you see my preparation, it was elaborate.”

Back in the camp, the 45-year-old mother of 10 sells air freshener, perfume, and incense to fend for her family.

“I make between N2,000 and N10,000 every day. It depends on patronage. The prices of my wares are from N300 to N3,500 per unit. I sell my wares in the camp or any market like Asokoro or games village,” Kurmi explained.

Although she experiences low patronage, she hopes to get enough money to venture into a profitable business like fish farming.

‘KOSE CHANGED MY FORTUNE WHEN I LEFT GWOZA’

The story of Ruth Steven comes with a twist, because unlike others who were engaged while in their communities, she was fully dependent on her husband.

Ruth, her husband, and four children escaped Gwoza to Bakassi camp, one of the oldest IDP shelters in Maiduguri, in 2011. A year later, limited space forced them to exit the camp in search of a rented apartment.

“Mama Kanka, hope kose is still remaining?” a girl asked as the reporter met Ruth by her food station, on a bright Saturday morning in Maiduguri, the Borno capital.

Every morning, for the past six years, Ruth has sold fried bean cake, known as kose or akara, at the front of the College of Nursing and Midwifery in Maiduguri.

Prior to her ‘newfound love’ as she calls it, she got tired of staying in the house and unable to support her family as she desired, as she was fully dependent on her husband who works as a storekeeper in a food company.

Narrating her experience, Ruth said on a certain afternoon in 2014, an idea came to her to engage in prayers for three days, and she hoped it would grant her a solution to her financial misery.

Fortunately, on the third day, her breakthrough came when a neighbour asked her if she could fry kose for a living. She was given N2,000 to start the business, an amount she received in tears due to the sudden turn of events.

“That was how I began counting N10, N20, N50, and now N1,000. Kose made me laugh o. If I buy anything, it is because of my kose business. I am fresh because of kose. Anything I do in the house, it is because of my business,” she said.

“If I have the opportunity to give a testimony in the church, I will sing ‘anything you see on my body, it is Jesus that did it and kose’. I feel very comfortable now because I don’t beg my husband or brothers for money. I can buy anything I want for me and my children.”

On a daily basis, Ruth says she earns between N10,000 and N19,000. She also uses her proceeds to buy foodstuff in the house.

She considers herself lucky because her husband is supportive of her business. According to her, he helps with house chores, prepares the children for school, and in fact, waits for her to return every night before he sleeps.

Nursing or teaching are the only options that will make her consider leaving her kose business. She gushed about her attraction to the white uniforms of the nursing students whenever they patronise her.

“If I leave my business, I will go to the university or attend this nursing school where I sell for the students. Wow! I want to be a nurse! When I see them inside their white gown, I am always jealous because I have always imagined myself inside the uniform. Or I could be a teacher,” the 32-year-old said with excitement.

She almost got admitted into a school of health in Maiduguri, but she turned it down because she feared she might not be able to sustain her fees if her business stops.

“If I have enough money, I can continue my education. But if I abandon my business, who will help me? If someone gives me the money to return to school, I might consider dropping all that I am doing and go. But I am saving for my education.”

‘I AM HAPPY MY CHILDREN CAN GO TO SCHOOL BECAUSE OF AKARA’

Zainab Usman had just finished selling bean cake, known as akara, and was playing with her children when this reporter entered her well-spaced apartment around Meiwa road, Maiduguri.

As she explained, in 2013, she became fed up with the frequent attacks in Bama local government area and decided to leave. She pleaded with her husband, whom she had been married to for 30 years, to follow them but he declined.

Since then, she has taken up the responsibility of supporting herself and her nine children with her trade.

Now living in Borno’s capital, she says she has no reason to look back because her business is flourishing. From her daily sales, she earns between N5,000 and N9,000.

For her, it is enough to pay her children’s school fees, feed, pay rent, and settle other bills.

“Here, I live peacefully, but if I relocate to Bama, I won’t be able to sleep well. I am interested in training my children to the highest level education and not abandon them. I am happy that my children are going to school out of akara,” she said with a grin.

She hopes to save enough money to get a grinding machine for herself and other akara sellers within the community, because they risk their lives to grind their beans either early in the morning or late at night.

These five women exemplify other female IDPs who have defied stereotypes and assumed new status as providers and breadwinners, and they want the world to see them as such — not as distraught or beggarly widows.