Last year at about this time, on July 23rd to be exact, my good friend and the Catholic Bishop of Sokoto, Dr. Mathew Hassan Kukah wrote a piece titled, Ramadan in the Time of Boko Haram which enjoyed wide circulation. It was also posted on an email list serve to which I belonged. After reading the piece, I posted the following comment:

Here’s Bishop Kukah, the Bishop of Sokoto no less, mixing several issues up and missing the point once again.

I was happy to leave the matter at that. Shortly after posting that comment, however, a barrage of other comments came in as other members demanded to know what the good Bishop had mixed up and where he missed the point. All of those who commented were Muslims. I consider one of those comments by a practicing medical doctor and professor of medicine, which I reproduce below, particularly disturbing:

The question is what if the writer was a Muslim? The issue is can we seperate (sic) the message from the messenger…. I have a feeling if I substituted the name (a bad placed the name) Mohammed Mohammed as the writer it would be viewed differently and accompanied by indifference and apathy.

Advertisement

The preceding comment is clearly incoherent but the message in it is, nonetheless, unmistakable: if Bishop Kukah were a Muslim it is unlikely I would comment in that manner. I was literally being accused of religious prejudice. The subtext, of course, is Bishop Kukah is beyond reproach. Once he spoke, everyone must keep quiet, especially if you are a Muslim. That is what rockstar image does to a good cleric.

I felt deeply wronged by the suggestion of religious prejudice and I said so at the time. I wondered why one Muslim felt entitled to agree with the good Bishop but denies another the freedom to disagree with him. I saw grave danger in conflating genuine disagreement over ideas and viewpoint with a confrontation of faiths or, worse still, conflating genuine disagreement with prejudice.

Bishop Kukah is a public intellectual. Once he places his views in the public space, even though he is a Bishop, Muslims must not be made to feel particularly disadvantaged when they find cause to disagree with him by the fact that they are Muslims alone. This is especially so where the subject matter affects their religion. In the absence of interfaith dialogue, how else could we arrive at interfaith understanding? I enjoy an excellent personal relationship with Bishop Kukah. I’ve been a guest at some of his public events, including a round table with former Secretary of State of the Vatican, Cardinal Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone in 2011. I’ve had cause to disagree with Bishop Kukah in the past. He has never made me feel my views are coloured by prejudice.

Advertisement

Beyond my deep sense of disappointment, however, I decided I owed it a duty to myself to exculpate myself from the charge of prejudice by illustrating where I believed Bishop Kukah had mixed things up and ended up missing the point. I instantly wrote a rejoinder to his piece and posted it on the list serve. Since that rejoinder a year ago, I have come under polite pressure to make it public from some members on the list serve who had earlier felt uncomfortable with my initial comment. I reproduce a slightly edited version below as the initial rejoinder was not meant for publication. I also reproduce Bishop Kukah’s piece, Ramadan In The Time Of Boko Haram at the end of my rejoinder for ease of reference.

The Rejoinder

Let us look at Bishop Kukah’s piece purely on its merit and the message it conveys and see what issues the Bishop mixes up and where he misses the point, starting from the story of Thomas and Christopher, two Christians stricken by hunger, thirst and exhaustion in a desert enclave. They stumble upon “an oasis” while facing the possibility of imminent death. They both make some assumptions about the people they are about to encounter, who happen to be Muslims and who could determine whether they live or die. Each chooses a survival strategy.

Christopher decides to choose the survival strategy of accommodation, on the basis of the assumptions he made, by changing his name, not his faith, because of his expectation that the people in whose hands his survival could depend, would respond in kind. He specifically insists that his faith will not be affected by his strategy of choice. “‘Relax’, Christopher said to his rather confused friend, ‘deep down inside me, nothing has changed in my faith’”. Thomas, on the other hand, chooses a strategy of defiance and death. He is not prepared to make the kind of accommodation Christopher makes. At the end of the day, the guy who chooses accommodation loses out while the guy who doesn’t wins, even though the outcome is, ultimately, not decided by the strategy itself but by the people about who both Christopher and Thomas are wrong.

Advertisement

To Bishop Kukah, Christopher made spiritual suicide by accommodating and making concessions to his Muslim hosts even in the face of death. “How many times have we been tempted to make spiritual adjustments, so as to extend the reach of our career or achieve some material benefits? The foundations of the convictions of our faith should be such that they cannot be shaken. Poor-fake Mustapha, if only he knew that faithfulness pays.” But did Christopher/Mustapha really make any “spiritual adjustments” as Bishop Kukah claims. What spiritual adjustments did Christopher make “to extend the reach of his career or to achieve some material benefits” in Kukah’s piece? If we extend the same logic and argument to Bishop Kukah’s middle name, Hassan, his choices and that of Christopher are basically the same. In a plural and multi-religious society like our own, tell me what lesson this story holds for Nigeria of today, about interfaith dialogue, accommodation and religious tolerance.

But Bishop Kukah is not done. He actually goes further to suggest that those Christians who visit Muslims to break fast with them are hypocrites, of little faith, who only do what they do because they are after some material gain. “Do they ask the Muslims to fast with them at Lent?” he asked. Yet, if the good Bishop were to be honest with himself, he would admit that fasting is a matter of personal choice for individual Christians and Muslims, not a matter of tit-for-tat. It is not my business to dwell on whether the Bishop is right or wrong but I am obliged to ask if Bishop Kukah’s characterisation of these breakfast events is true or false. Are majority of the Christians who visit Muslims to break fast with them the politicians he claims they are? Who are these Christian politicians who visit Muslims to break the fast? Or can we draw conclusions from what is happening in Kaduna State Government House, Bishop Kukah’s home state, where he is yet to be invited as a breakfast guest, and generalize to make it look like this is what is happening in the communities in which we live?

What of other men of God like Bishop Kukah, who do the same? Not being the politicians he has come to detest, does the Bishop make exceptions for them in his piece? Or, if we want to be charitable to him, we can ask the Bishop to explain, on a scale of one to ten, what number represents that of the politicians who are doing this because they have something to gain. What, for that matter, is wrong with Christian politicians reaching out to their Muslim counterpart during the month of Ramadan? Does that necessarily translate into the politicization of Ramadan or “the elevation of this sacred month to the pantheon of national politics” as the Bishop has claimed?

A professor of political science had this to say on Bishop Kukah’s inconsistent position on this subject, “What has happened to our bridge builder’s memory? Just ten months ago, (Sept 12, 2012), while commenting on the national protest against the hike in fuel prices, this is what Bishop Kukah said:

Advertisement

‘I think the events of the past eight months are quite significant: 20 or even 15 years ago Nigerians would have been out on the streets calling for the military on the fuel subsidy. As we now see, a delegation of Muslim leaders went to the cathedral in Kano to address the Catholics whilst they were worshipping. We have cases of Muslims banding together and creating a wall to ensure that Christians can pray freely. His Grace Onaiyekan breaking fast with Muslim faithful during Ramadan. We have the same scenarios in Lagos. I think that many Nigerians are gradually moving beyond their religious frontiers.’

What has happened since then? Why does Bishop Kukah suddenly now refer to this joint Muslim-Christian breaking of fast as a “stunt”? Isn’t this symbolism (of the rich and powerful) even more necessary in Northern Nigeria in this “time of Boko Haram”? In my opinion, Bishop Kukah’s new position amounts to little more than a denigration of the brave and noble acts of people such as His Grace Onsiyekan.”

Advertisement

For the record, I was among that delegation Bishop Kukah spoke about in the professor’s comment above. We visited not just the Catholic Church and spoke to the congregation from the pulpit, we went round all the five churches representing the different components of CAN and did the same. We also arranged visits and accompanied the leadership of Kano State CAN, under Bishop Ransome Bello, to five selected mosques in the state where they addressed the congregations in some mosques and the imams in others. Thereafter we took them round to selected community leaders in the state such as Alh. Aminu Dantata, Alh. Magaji Dambatta, AVM Mukhtar Mohd, Alh. Yusuf Maitama Sule, Alh Bashir Othman Tofa and many others who took turns to reassure them of the safety of Christians in Kano State and pledge to do their utmost best to ensure religious harmony between Muslims and Christians in the state. This kind of thing has never been done before in Kano where Christians were taken inside the mosques and entertained with food and drinks donated by congregations and facilitated by Imams.

Shortly after these series of visits, Shekau released a video making reference to our work and threatening to make us pay for bringing Christians into mosques and desecrating the places of worship of Islam. Towards the end of the week, on Thursday, January 20th 2012 to be precise, Kano was attacked and hundreds of people lost their lives. Some people blamed BH for those attacks. Others suspected government involvement in order to deflect attention from the fuel subsidy riots raging at the time.

Advertisement

Now, I’m not claiming any linkage between our work and the January attacks but I’m very pained by Bishop Kukah’s latest rant because it totally misrepresents and denigrates the good work some citizens are engaged in, especially in the North, sometimes at great personal risk, to bring about interfaith understanding and dialogue which is required for lasting peace.

Last week Mr. Solomon Dalong, a lawyer from Plateau State, led a mixed group of Muslims and Christians to break the fast with Sheikh Dahiru Bauchi, an influential Muslim cleric, in his Kaduna residence. I listened to what they had to say over the Hausa service of the BBC. They spoke of peaceful co-existence between Muslims and Christians. They appealed to Nigerians to live in peace. We don’t know whether they meant it or not but it sure is better than incitement. Last Christmas, our organization, the Kano Covenant, visited our Christian brothers and sisters in Kano State, including the state leadership of Christian Association of Nigeria. We took with us a truckload of food items, including several bags of rice, cooking oil and other items. Kano is at least 95% Muslim. We have absolutely nothing political to gain. Instead of weaken our faith, we actually felt like better Muslims by the action we took. And I can say without any fear of contradiction that these visits and gestures help foster interfaith understanding and peaceful coexistence and we will be worse off without them, not better off. We know the value of this kind of visitation in Kano State. Since we started our outreach program, interfaith harmony had greatly improved in the state.

Advertisement

As far as I know, the practice of Christians visiting Muslims during Ramadan and vice versa, which Bishop Kukah has now come to condemn builds bridges and fosters greater understanding and it is a precious little we can use to expand the frontiers of interfaith dialogue and send the message out to the extremists that we stand as one, especially in a period like this when tension arising from the activities of Boko Haram is high. It may be only little symbolism but it is a powerful little symbolism we need so badly at this point in time.

The Christians who visit Muslims during Ramadan do not consider themselves hypocrites or of little faith any more than the Muslims who visit Christians during Christmas do. In the end, this interpretation of events is Bishop Kukah’s alone and we are not obliged to agree with him. The danger in this kind of interpretation is that it validates and strengthens the extremists among us and it threatens to block the few avenues available for creating greater Christian/Muslim understanding. These visits are taking place mostly in mixed Muslim/Christian communities where dialogue is needed the most. We should encourage them, not discourage them like Bishop Kukah has done in his piece.

It is all so nice and hip to condemn corruption and waste of public funds in the name of Sallah, Christmas, Hajj, Umrah, Christian pilgrimage and such other exotic rituals mostly reserved for the rich. It is the in-thing. I don’t support this wasteful practice myself, where governments spend public funds to distribute largesse or sponsor pilgrims. I condemn it with every strand of moral fibre in my being. But talk is cheap. Hear the strength of Bishop Kukah’s moral fibre speak for itself:

The distribution of Sallah cows, rams, rice or chickens has become an industry in government. I have been a beneficiary of these donations, but I am worried because I do not need most of what I receive. I know that there are too many people who need it more than me… There has been too much waste and hypocrisy in the name of religion by the elites in Northern Nigeria and it is time to take on this problem head on.

So what stops the good Bishop from rejecting these “donations”? Why isn’t he in the frontline of “taking on this problem head on”? Why is his fabled courage deserting him in this case? I know someone who would. The late Gani Fawhinmi for example. Or the late Hamza Adamu Chafe, a little known former local council chairman from Zamfara State. A preacher should practice what he or she preaches. It is not enough to say, “I’m sorry, I’m weak. I can’t walk the talk”. Aren’t we all? So, what makes preachers different from the rest of us?

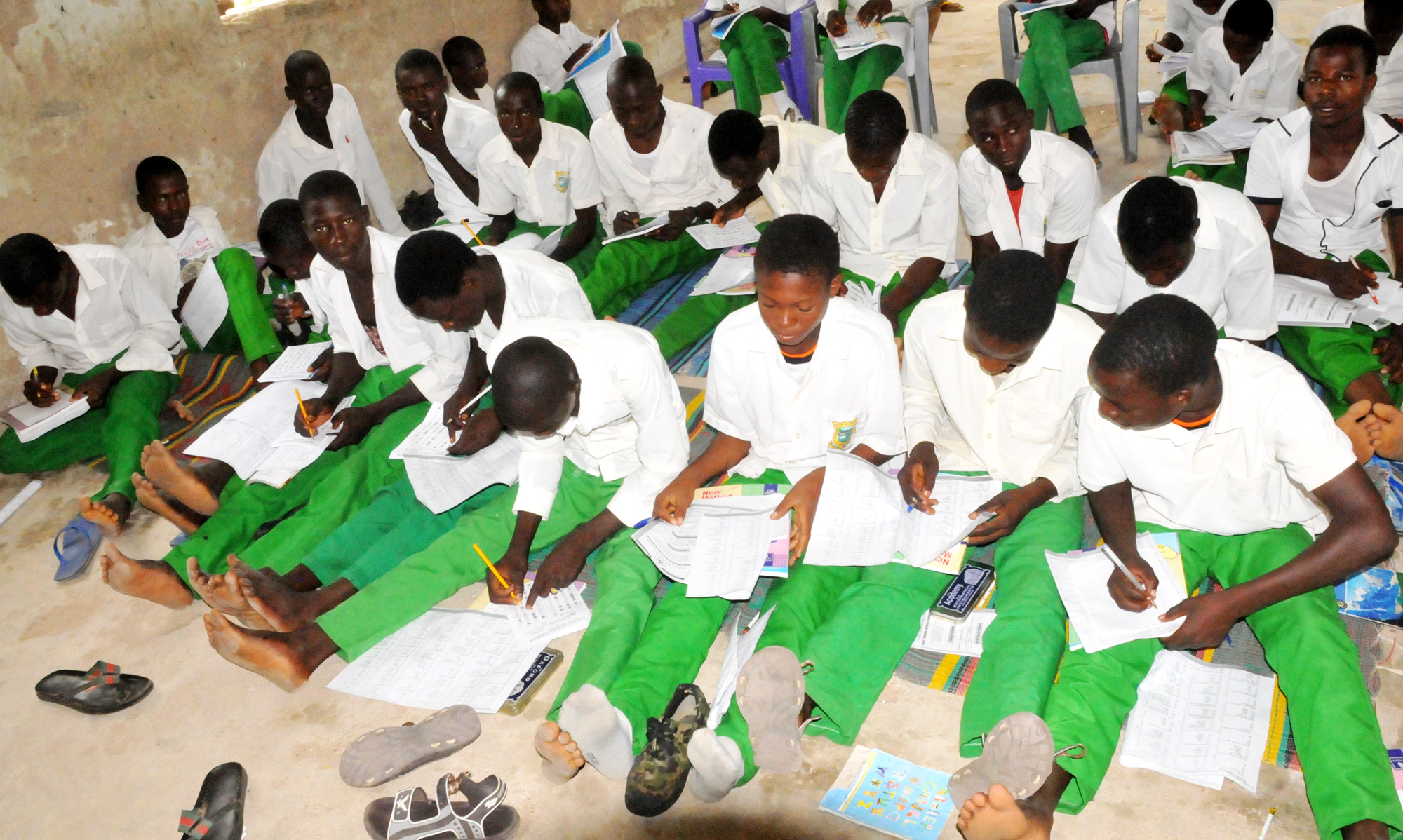

For a piece titled, Ramadan in the Time of Boko Haram, running into 25 paragraphs, you would expect the Bishop to show the nexus between the two. He begins to do that in paragraph 18. Unfortunately, he misses the point by associating Ramadan with suffering and squalor, calling for the redemption of “those who have been condemned to a life sentence of Ramadan which has kept them hungry not for thirty days but for life”. “What about those Muslims who have been serving a life sentence of hunger, sickness, destitution and squalour?” he asks and then provides his own answer, “For them, life has been and will remain a permanent Ramadan”.

Muslims, the poor and the rich, do not relate to Ramadan in those terms. Ramadan is not a mode of punishment from which Muslims need to be salvaged. It is not synonymous with hunger, sickness, destitution and squalor. It is an act of worship which Muslims are happy to partake in. It is disrespectful of Muslims to speak of Ramadan in those terms and I’ll hold the same view if it was a Muslim who makes the same analogy. I remember someone posted a story on Mary Magdalene on this same forum and her relationship with Jesus Christ. We all condemned the lack of sensitivity in that action and asked the fellow to apologise. But here we are pretending it is OK for Bishop Kukah to describe one of the fundamental pillars of Islam in those terms. I expected a little bit of discretion not just from Bishop Kukah but also from those who condone and support what he had to say. Am I missing something here?

Thankfully, there are issues over which the Bishop and I agree and these constitute the bulk of his piece. But on those issues I feel the Bishop has misfired, I’ll make my views known. He’s not infallible, yet. And the Bishop Kukah I know will not take offence because I disagree with him. After all, he’s the master of “telling truth to power” which, I believe, is what he intended his piece to be. I’m proud to walk in his footsteps, even if awkwardly, as I’m sure it might seem to some.

Mallam Bashir Yusuf Ibrahim, a seasoned politician and media executive whose op-eds have been featured in both local and international media. Mallam Bashir is also currently the National Chairman of the Peoples Democratic Movement (PDM). Bashir Yusuf Ibrahim can be reached at [email protected].