Liberian Ebola survivors are frustrated by the lack of government involvement in their efforts to rebuild their lives, and their discontent has been further heightened by the emergence of reports confirming government profligacy in the management of donor funds sent to combat the virus and quicken the country’s recovery from the epidemic.

Foday Kutuku Sheriff is hurriedly exiting the building housing his office for an important engagement when he receives a verbal request for an interview. Already late for this engagement, Sheriff politely asks for a rescheduling. But when he is told that the interview will focus on the Liberian government’s handling of donor funds to fight Ebola, he immediately changes his mind.

Sheriff is suddenly so eager to speak that he doesn’t see the need to return to his office. Right there on Carey Street, Central Monrovia, he points to a corner where he can grant a quick interview. His anger with the Liberian government is palpable, almost contagious. When he speaks, it is with the rage of a lion angling to prey on an antelope. Sheriff is irritated that Liberian Ebola survivors cannot get their lives back on track, and he is infuriated that this drawback is “down to corruption” in high places.

“The people in our government are very corrupt; they are very good at eating money – eating public money,” Sheriff yells. “I tell you no lie; our people here are very good, they are professionals at eating public funds.”

Advertisement

JOHNSON-SIRLEAF’S EMOTIONAL APPEAL

In October 2014, Liberia president, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, begged the world for help. Liberia had spent the previous 11 years recovering from its brutal civil war, and she reckoned that Ebola was threatening to “erase all the hard work”.

“This fight requires a commitment from every nation that has the capacity to help – whether that is with emergency funds, medical supplies or clinical expertise,” she wrote in a widely publicised ‘Letter to the World’ delivered via BBC.

And so the funds started coming in. As at October 17, 2014, funds pledged from outside Africa alone to the three Ebola-hit West African countries were already in excess of £1.3 billion (more than $2billion). By July 2015, the United Nations announced that donors had pledged a total of $5.2 billion, which far outweighs the $3.2 billion all three countries requested to “return to the progress of our pre-Ebola trauma”.

Advertisement

Clearly, the planned return to pre-Ebola state would never have excluded the victims whose lives were shattered. In Liberia, the outbreak sent half the heads of households out of work, while women – who account for more workers in the non-agricultural, self-employed sectors – were among the hardest-hit. Therefore, Ebola’s destruction of livelihoods sorely needed to be addressed.

This much was acknowledged at a United Nations meeting in July 2015 where President Ernest Bai Koroma of Sierra Leone, speaking on behalf of the three Ebola-plagued countries, said: “Humanity sometimes displays short attention spans and wants to move to other issues because the threat from Ebola seems over. The threat is never over until we rebuild the health sector Ebola demolished, until we rebuild the livelihoods in agriculture it compromised…” (For the records, Sierra Leone is battling with its own scandal of corruption and mismanagement of Ebola funds.)

So it is a huge shock that Liberian Ebola survivors cannot point to a single thing that the government has done to help their post-crisis recovery.

LEFT IN A LIMBO

“The government said anything pertaining to you was contagious, so its task force destroyed everything we had, but they have not been able to give us anything since we survived – not even a single mattress,” says Josephine Karwah, who lost a seven-month pregnancy and nine members of her family to the virus.

Advertisement

In September, it will be one year since she conquered Ebola, but she says she doesn’t even have a roof over her head yet, as she has been putting up at Sanker Clinic, located in Margidi County, where she sleeps at night before rushing out in the morning. None of her relatives will take her in; that is the extent of stigma confronting Ebola victims.

“While international agencies and NGO paid us different sums ranging from $80 to $150 for a period ranging between three and six months, we have not received a dollar from the Liberian government.”

She lists some of the agencies that have offered financial and material aid to survivors as the International Rescue Committee (IRC), World Food Programme (WFP), United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF), Save the Children, Young Life, The Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA)) “and some other small NGOs”.

“UNICEF pays each survivor $150 monthly for six months. WFP gave us cell phones and $85 for three months. Save the Children gave us $400. ADRA gave us mattresses. Young Life housed all survivors for a few days after leaving the ETU, and gave us psycho-social support and counselling,” she says.

Advertisement

Like Sherrif, Jospehine thinks Ebola funds were mismanaged.

“Yes, I have that feeling because the government has been absent in our entire post-Ebola recovery,” she says. “Survivors were discharged from the ETU and left alone to hop on motorbikes.”

Advertisement

She is ever grateful to her non-governmental benefactors, but expects far more from the government.

“Look at me; I lost my livelihood, my parents, my home – everything. So government needs to reintegrate us. They need to settle us, settle us with something good that we can restart our lives with.

Advertisement

“People who want to go back to school, provide them the scholarship. Those who are interested in trades, provide them with the skill. That is the way to help us rebuild our lives – not to leave us in a limbo like this.”

TEARS FOR SURVIVORS

Prince Diane, who lost his mother-in-law and a niece to the virus, is two months away from his survival anniversary. And just like Josephine, he is still waiting on the government to compensate survivors, in any way, for their loss.

Advertisement

“I think survivors need a sort of resettlement package that will enhance their lives,” says the survivor, who continues to experience heart aches, feeble stamina and a fading memory.

Without friends, a job and a home, Prince laments that survivors have no one to turn to, save the people in government.

“When I was taken to the ETU, everything I had was destroyed. On my return, the only thing I saw was my floor,” he says. NGOs have been giving us money, but the truth is that this won’t solve the problem.”

There have been promises of government aid, but Prince thinks a year without actual help is taking too long.

“It is almost one year, and there has been nothing from the government. Government needs to devise a resettlement package for survivors.

“There are traders who have lost everything. There are orphans who cannot go to school. Lots of survivors were evicted by their landlords. I went to Lofa County the other day; I saw survivors and I shed tears. If you went to Nimba and you saw survivors, you would cry.”

A CRY FOR HELP

Henry Tony does not want to be drawn into talks of mismanagement of funds; his only interest is his “survival”, which he says is at risk.

His wife and son were consumed by the virus; and having lost his job, home and sense of belonging in the community, he says he is need of “government help” just like other survivors.

“We need to be reintegrated into the society. Stigmatisation is one of the major problems we are facing. The government should push us to the society; let the people know how that we are still important to the society,” says Henry, who now volunteers for the Ebola Survivors Network (ESN).

“Also, we need a settlement from the government. NGOs give you $150 and you have a house rent of $200 waiting to be paid at the end of every month, for how long will you maintain your sanity when you are not working? We need jobs; we need skill training programmes. I am a mechanic, a driver and a counsellor, but I need something to do for survival. Ebola survivors need help.”

WHERE ARE THE EBOLA FUNDS?

Patrick Farley, president of the ESN, wants to know what has happened to “all the funds” announced on radio as donations to Liberia’s Ebola fight and recovery. Although he admits that no one is guilty until so proven by a court, he is convinced that the quality of healthcare to victims and the absence of support for survivors are clear indications of financial hanky-panky.

“The quality of care is not commensurate with the amount of money that has been sent into this country. That one, for sure, is the reality. Everyone knows about that,” he says, stone-faced.

“The least amount of money I should be receiving as per my resettlement package is $5,000. We have survivors who lost 20 members of their family, some who lost 15 members. A 20-year-old now has five children to look after.

“You think she can ever go to school? Or these children will? She has to rent a house and they have to feed? You think they can ever be self-reliant without external help? We know the government can come in with the contribution. The money was there, and the money should be there. The money is there.”

For Patrick, the post-survival mess is too complicated for the government to be entirely absent. Among those in the survivors’ network he chairs are people with post-Ebola syndromes such as ear problems, unclear vision, internal body pains, impotency and psycho-social disorders.

He is baffled that after a recent protest by health workers whose hazard allowances had not been paid, the government announced that the funds had all been expended.

“We think if that has happened, then the government has not done well for its citizens. I am saying it without fear or favour,” he says with a wry smile laced with discontent.

“We don’t know where the funds are, but we heard on radio that there were funds that came in for fighting Ebola and fighting Ebola isn’t only about the treatment being given at ETUs, it is also about helping survivors whose lives have been shattered by the virus.”

TRACKING THE FUNDS

The worries expressed by the likes Patrick and Josephine were not confined to Liberia. As the concerns also grew in Nigeria, another West African country where the virus raged but was quickly curtailed, BudgIT – a firm with a growing reputation for employing technology to spawn citizen participation in informed budgetary conversations – partnered with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) to set up a website visualizing all funds allocated to the affected countries.

“As citizens of the region and indeed the world, it is important that we ensure transparency and accountability regarding the use of funds,” Oluseun Onigbinde, its lead partner/co-founder, says.

“The Ebola Fund Watch aims to understand how emergency funds were applied to survivors, victims, healthcare workers, institutions and other beneficiaries; and to challenge governments of affected countries to ensure that the funds are expended effectively and not used as a tool for corruption.”

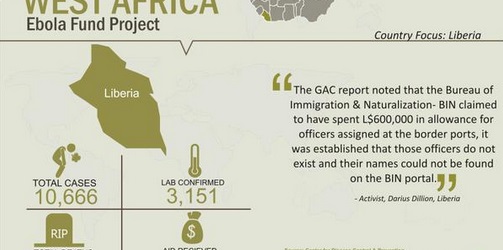

According to that website, Nigeria, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea had received a total of $2,096,721,772 as at June 2015. Understandably, Liberia, being the worst hit, has been the biggest beneficiary, pocketing a total of $991,237,027. The narrations of survivors reflect that some of these donations were not directly remitted to the Liberian government – those made to ADRA, WFP, UNICEF, ICRC, for example.

But a lot others did go directly to the government. These include (but are not limited to) $5.6million from World Bank for food supply to quarantined and Ebola-affected population, a $52million World Bank grant from emergency response to the crisis, $390.4million US assistance on response efforts, $84,000 by the National oil Company of Liberia and $75,000 by the Liberia Petroleum Company. Yet, these figures are far from exhaustive, which is why Nigeria’s $500,000 (donated despite its own economic quagmire) is, for example, not captured.

These figures were put to Sylvester Tevez, national chairman of the Organisation for Better Liberia (OBL). While he says he cannot confirm the receipts made by the government, he is certain that there was a “huge inflow of cash”. His opinion is that the Liberian government is “unserious” about helping survivors reclaim their battered lives.

“Let me bold, Ebola money cannot be properly accounted for, because we saw the auditing of some of the institutions that were in the control of the funds,” a visibly-angry Sylvester says.

“And the president came out using all kinds of statements to shield these individuals. Imagine the woman in my neighbourhood who lost six children to Ebola, and the government has no mechanism in place to help her restart her life?”

THE BIG INDICTMENT

In early 2015, Liberia’s anti-corruption watchdog audited just a fraction ($15.1million) of the funding to fight the epidemic spent in the three months of August to October 2014. Its conclusions were damning: some $800,000, most of which passed through the defence ministry, could not be accounted for!

“The conduct of the affairs of the National Ebola Trust Fund (NETF) were marred by financial irregularities and material control deficiencies for a number of transactions carried out by the Incident Management System and the eight Implementing Partners of the NETF,” General Auditing Commission (GAC), as it is known, said in a report published on its website in April.

In one of the many shenanigans it uncovered, GAC observed that US$672,617.56 was received and disbursed by the ministry of defence without relevant supporting documents. “The disbursement was made for fuel, feeding, daily subsistence allowance, communication, medical and training, tentage repair, repair and maintenance, among others,” it said.

Elsewhere in the report, it found loopholes in the payment of allowances to some Bureau of Immigration (BIN) officers in various counties. “The amount of L$853,875.00 for allowance was paid to 68 officers in 10 counties who could not be physically seen or whose names could not be traced to the daily attendance records for the period under review,” GAC said.

GAC said it could not physically verify seven Yamaha generators valued at $1,085.00, and noted that three vehicles were purchased for $62,720 without official authorization.

The audit – which did not include donations from international organisations such as the World Bank, USAID) and other foreign donors whose contribution did not flow through the NETF – is littered with instances of phantom, unauthorized and unproven expenses. Attempts to get the reactions of NETF and ministry of defence officials to the audit were unsuccessful due to their unwillingness to speak with the media.

Little wonder, after seeing GAC’s report, Sylvester said: “Wherever it is that you are taking this [interview] recording to, let the people of that particular country get to understand that if anybody wants to give subsidy to Liberia, they should rather send an independent team that will monitor the financial aspect of it, because we don’t trust our people here.”

GOVERNMENT EXPLANATION AND NAME-CALLING

Johnson-Sirleaf’s response to the report was that there might have been procedural errors in expending the funds, but this was intended to save the lives of the hundreds every day.

“That fund was put there at the time when hundreds of people were dying… when we had chaos. In the midst of chaos, something has to be done, and so, I am quite sure that it reflects the context of the kinds of urgency that was required in some cases,” she told the local media.

“…if someone says that they have to buy a bus to carry people when a hundred people are dying on the street and they did not go through a bidding process, I will leave it to you to say which was better; to say to have bought the bus to save the lives or for them to have taken two weeks to go through a bidding process.”

In May, NETF wrote a 36-page letter to Yusador S. Gaye, the auditor-general, branding the GAC “incompetent and unprofessional”. Its response, peppered with name-calling, mirrored the president’s.

“Madam Auditor-General, so urgent were the interventions, then required and undertaken, that it was often just simply not practicable, indeed, not even sensible at all, to insist on contracts, tax clearances and the like, without which, you appear to believe, that everything else that was done even under those circumstances, just simply do not matter at all,” it said.

“The perspective of yours is unfortunate and regrettable coming as it does from the Auditor-General of the Republic of Liberia, the Supreme Audit authority of this country….

“You have also NOT even as much considered all relevant pros and cons and different perspectives BEFORE drawing the conclusions indicated in your report. For that reason your report reads as if the author lives in and has written, not about Liberia but an entirely different country; or, for that matter, an entirely different planet. You have irresponsibly damaged the hard-earned reputation of members of the senior leadership of the NETF…”

NETF ended by threatening a lawsuit against GAC if the report wasn’t withdrawn from public domain within 24 hours. It is now three months since that threat was issued. The report is still on the GAC website – and there has been no lawsuit yet!

Add a comment