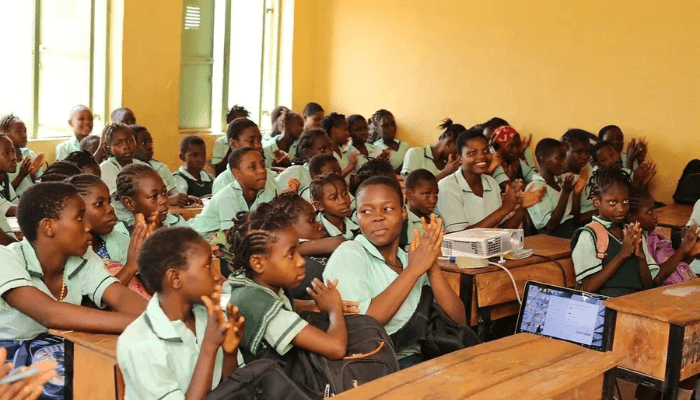

There are weightier matters in the nation’s pre-tertiary schooling than its current system.

The other day, the Minister of Education, Dr Tunji Alausa, took the stage at the 2025 Extraordinary National Council of Education conference, the nation’s highest policy-making body, in Abuja, and sounded like a declaration to adopt a straight 12-4 system of education for the country. It was promptly reported by a chunk of the mass media as a decision already made by the government. One online newspaper was categorical in its headline and opening sentence: “FG Abolishes Junior and Senior Secondary Schools, Introduces 12-year Basic Education… The federal government has announced the scrapping of the Junior Secondary School (JSS) and Senior Secondary School (SSS) systems in Nigeria, introducing a compulsory 12-year uninterrupted basic education model.” This turned out to represent the bandwagon news reporting of that event.

In less than 24 hours after, what had been reported as an official announcement was recast by the ministry as only a proposal meant to elicit some informed responses from the minister’s audience populated mainly by high-profile education professionals and technocrats. Whatever the effects of the teaser, the ripples are not likely to fade into oblivion anytime soon.

But first, a necessary digression. For some time now, the Federal Ministry of Education has been a theatre of some sort, a source of poorly-prepared policy pronouncements that get to the knowledge of Nigerian citizens who are left to figure out their authenticity and workability all by themselves. To mention just two instances. At the twilight of the administration of President Muhammadu Buhari, it was announced to the praises from many quarters that the subject of history would be returned to the secondary schools’ curriculum. Sincere concerns and questions were raised about some aspects of that move. Government grandstanding was recorded here and there. Today, it’s difficult to speak confidently on its implementation.

Advertisement

Two, the immediate past Minister of Education, Professor Tahir Mamman, woke up one morning and declared that only prospective candidates who were 18 years and above would be admitted into higher institutions of learning. All hell broke loose. People with either credible or phoney arguments jumped into the fray. The man received blows he never anticipated. The most bizarre opinion I read that period came from a certain commentator whose name I had no reason to wish to remember. He held up Mamman’s pronouncement as a ready evidence for his conviction that a particular region of the country simply can’t produce a quality head of this all-important segment of our national life. Yes, the atmosphere produced by that ill-thought decision became that obscene.

The former minister did reverse himself eventually and the episode was believed to be his major undoing when President Bola Tinubu reshuffled his cabinet last year. But as soon as the current education helmsman took office, it was also reported that he rescinded the age limit resolution of his predecessor to the chagrin of those who thought that the matter had already been laid to rest. Like some others before it within the same ministry, that debacle raised issues of impropriety, inconsistency and communicative summersault.

The more recent subject of which structure to adopt for the nation’s pre-tertiary education schooling should be promptly and expertly handled before it’s added to the burdens that are conspiring to further jeopardise a sector which was once vibrant and globally competitive. That day, Dr Alausa expressed his views pointedly: “It is important to acknowledge that while the 9-3-4 system of education has its merits, it also has drawbacks, such as the need for students to work to further their education… It is therefore prudent to transition from the 9-3-4 to the 12-4 system of education. By doing so, Nigeria will align with global standards in preparing students for better tertiary education.

Advertisement

“A 12-year basic education model will ensure a continuous, uninterrupted curriculum, promoting better standardisation and fostering quality assurance in the education system…. I am sure many of you have heard about the challenges we face as a nation with talented, bright students being disenfranchised from pursuing tertiary education. In any society, it is crucial to standardise the education of highly functional and exceptionally gifted students. We are now preventing these students, after finishing secondary education at the age of 16, from attending university until they are 18. This delays their development and harms their futures. These students are capable and brave. If we leave them idle, we risk exacerbating mental health issues.” Well-crafted argument, maybe. But so also was the rhetoric that preceded the previous shifts in our educational models.

Meaning, the real problems may not be with any particular model but with factors like conceptualisation, human, financial and material resources, mobilisation and execution. I recall that when the 6-3-3-4 was inaugurated in the 1980s, the loudest selling point was the need to promote vocational learning early enough. The assumption then, rightly or wrongly, was that adolescents and teenagers were naturally positioned to embrace and run with jobs that were outside the white-collar bracket but were beneficial and profitable. All they needed was early exposure, it was vehemently argued. That thinking surely wasn’t off-track. But where did all that lead us? The proverbial baby was thrown away with the bath water, of course.

Now, the education ministry is saddling itself with what might not even be an issue in the first place. And it isn’t peculiar to it. At different layers of government in Nigeria, there are numerous cases of ill-conceived or abandoned mental, social, economic, political and physical projects, the last type being the most noticeable. In a bid to achieve so-called legacy programmes, all sorts of ideas are rushed through the mills at the expense of huge monies, energy and time.

It’s interesting that the minister has put forward as one of his premises the age-limit question. Has he critically thought of the factors responsible for parents pushing their kids into creche, kindergarten and nursery earlier than what obtained in previous generations? Six years of age used to be the benchmark for primary school entry in those day. That was when parents led quieter and more organised – not necessarily richer – lives, when socio-economic realities had not become this vicious, and certainly when it was a well-received norm within Nigerian communities to send children to elementary schools not earlier than the stipulated age. And rat race hadn’t become common.

Advertisement

There is every indication that we need to spend less time arguing about which formula suits the country better than the weightier matters that have undermined our educational planning for too long. This is particularly painful because the nation has been swinging between giant strides and underachievement since 1955 when the Universal Primary Education (UPE) made its debut in the western region. Lagos, the then federal capital, and eastern Nigeria followed two years later. The launching of the Universal Free Primary Education scheme in 1976 and the ratification of the National Policy on Education in 1977 both signified the desire of government to prioritise basic learning.

Yet, setbacks, many of which ought to have since been tackled frontally, have continued to beg to be taken a bit more seriously. Teacher and child welfare. Quantity and quality of educational personnel, facilities and materials. Teacher training and retraining. Seamless, realistic, adequate funding. Overall optimal sectoral administration. None of these variables is rocket science. It’s okay if the honourable minister wishes to make a mark. And he actually has the very tasks that can help him accomplish that already cut out for him. Concentrating on one or two or three of these areas would win him the hearts of Nigerians instead of tinkering with a policy that may appear exceptional but could end up being only symbolic and peripheral.

Ekpe, PhD, is a member of THISDAY Editorial Board.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment