Paul Umuche, a 26-year-old Nigerian student, heard a huge explosion from his apartment in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city. He peeked through the window but was not sure where the sound was coming from, so he remained in his apartment. Russia invaded Ukraine the same day and the blast Umuche had heard some hours ago, was from bombing and rockets targeted at different parts of the city.

When Umuche read the news and saw that Ukraine was being invaded, he told his roommate, another Nigerian, that they had to leave the city. “The whole building was shaking from the impact of the blast and we became afraid,” he said. “I saw Ukrainians and other people running to different directions and it became clear to me that this has become serious.”

As news of the invasion circulated, frantic evacuation efforts across the country started. Umuche grabbed a backpack, packed a few of his stuff and headed to the train station. At the train station, more than 4,000 people – Ukrainians and foreigners – had swarmed around the premises and were waiting to take the train. The chaos of the invasion had caused delays with some services – airports, train stations and taxis shutting down. Umuche and his friend joined the queue and were hoping to take the next available train leaving the city.

“Everybody was confused and wanted to leave for safety,” he said. After waiting at the train station for some five hours, none arrived. Two hours later, three 22-seater buses arrived and Umuche and his friend struggled to get in. The buses were headed for Lviv, another Ukrainian city which shares a border with Poland.

Advertisement

They arrived at Lviv the next morning after driving for more than 10 hours. With no available means of transportation to the border, Umuche and other refugees had to walk for two days to the Medyka border which has become one of the busiest border crossings between Ukraine and Poland since the war started.

Poland was not the only destination. Thousands of refugees fleeing the war were arriving in Hungary, Slovakia, Moldova and Romania which shares a border with Ukraine. Germany and other European countries also opened their doors to accept the refugees.

“It was a treacherous journey,” Umuche recalls the walk to the border. “You don’t know if you would be attacked on the way or if the bombing or gun fires will hit you.”

Advertisement

Racism and discrimination at the border

Once at the border, Umuche and other foreigners fleeing the war said Ukrainian border guards would not let them pass through. “They asked us to go back and help their army fight the Russians. But this is not our war,” he said. “Why would they ask us to go back and help them fight for something we have nothing to do with?”

Umuche and other refugees refused to go back to Ukraine and instead, decided to fight back. For two days, during the stand-off with the border guards, they slept in the open under freezing temperatures and had no food or water.

On the third day, they decided to break the barricade which had been placed at the border and force their way into the Polish territory. “That was how we were able to get in,” he tells me. “If we had not taken any action, they would have forced us to go back and that was not an option.”

Umuche’s experience is not isolated. Thousands of foreigners, from mostly African or Asian countries who were fleeing the war, have shared their traumatic experiences of racism and discrimination at the border.

Advertisement

“When we wanted to enter the train, they started pushing us out and said it was only for Ukrainians,” said Alexander Orah, another Nigerian student who lived in Kyiv. “I saw that act as racist and discriminating because they were allowing only white people and some of them are not even Ukrainians.”

Orah, who was travelling to the Ukrainian-Polish border through Lviv, said the officials later told them that the train was for women and children only. But when women and children from Africa wanted to get in, they pushed them away. “So, it was obvious that they were discriminatory, so I urged people there to speak up against it because if they don’t talk, the practice will continue.”

As the discrimination continued, Orah started sharing posts about it on Twitter to raise awareness. The tweets sparked outrage and the next day, Orah and other foreigners were allowed to enter the train after spending a night at the station.

But that was not the end: After Orah and other refugees arrived at the border, the guards would not let them in and asked them to go to the Romanian border. “We started shouting again for them to let us pass but they stood their ground,” he said. “We trekked for more than four days to get here and this was what we faced.”

Advertisement

At the border, a barricade separated Ukraine from Poland. Orah said the purpose of the barricade was to separate them according to their skin colour. “They separated the Whites from the Blacks,” he said. “They allowed in 100 white people and only two Africans or two Asians. That was when we started protesting. I’d been there for a day and other people had been there for three or four days. So, we decided to break the barricade.”

When a scuffle ensued at the border, one of the soldiers pulled out his gun and threatened to shoot anyone who dared to move. “We told him that we were students and we were not in their country illegally to be treated this way,” Orah noted. The border guards called for backup who arrived a few minutes later, pulled out their guns and threatened to shoot them if they did not go back. “We knelt down and raised our hands up,” he said.

Advertisement

After the long stand-off, Orah and other refugees decided to break the barricade and started heading toward the Polish border. “They started beating us with batons and shoving us,” he recalls. “As we were running, we started pushing them down. They had to leave us when they saw that we had outnumbered them.”

Orah was at a reception centre in Poland for two weeks before moving to Berlin. “All my friends have been evacuated from Ukraine,” he said. “I abandoned everything.”

Advertisement

Surviving in Europe

Umuche and other refugees who fled the war are stuck in different parts of Europe with no idea of how their lives would turn from there. Umuche says “it’s a battle for survival in a no man’s land” and that “it is better than dying in a foreign war”.

The war, currently in its fourth month, has escalated into one of Europe’s largest refugee and humanitarian crises in recent times. Before the war started, Europe was facing a refugee crisis with millions fleeing the wars in the Middle East and political instability across Africa. However, the ongoing war has exacerbated the refugee problem in Europe. Since the war started, more than 14 million people have fled, according to the United Nations. The International Organization for Migration [IOM] said more than 8 million people have been internally displaced within Ukraine.

Advertisement

In Ukraine’s neighbouring countries, refugees are housed at reception centres where they are provided with temporary shelter, food and medical care. The evacuation efforts have also been overwhelming: Poland, which has taken more than 3 million refugees which represents the highest number, has asked for international support to help fund their efforts.

Less than two weeks into the war, the European Union (EU) activated its temporary protection directive and said the refugees are entitled to social welfare payments and access to housing, medical treatment and schools.

“The situation is precarious and that’s why we have to step in to help where we can,” said Orkan Oezdemir, a member of the Berlin house of representatives. To help their resettlement, the EU has granted Ukrainians the right to stay and work throughout its 27 member nations for up to three years. “What we do is that we move them out of refugee status and put them into standard status so they can live and work here for the next three years.”

Oezdemir said the refugees receive social security grants of €400 per month, housing and health insurance. Foreigners from third countries including Nigeria, who want to go back home, are helped with relocation plans and given €1000 to help in their resettlement.

“We have a lot of African students from Ukraine and what we want to do is to give them visas for three years to complete their studies in Germany,” said Oezdemir who is also the spokesperson for integration and anti-racism. “That’s what we are trying to do at this point in time but we are still negotiating with universities.”

In March, the Nigerian government began the evacuation of Nigerians fleeing the war. However, the evacuation process has come under criticism because of the way it was poorly planned. At the start of the war, there were more than 8,000 Nigerians, including 5,600 students in Ukraine. Only 1,300 have been evacuated as at March 28.

“There was no reason to go back home,” Orah said. “I love Nigeria and want to stay but I will always experience police brutality. That was one of the reasons I left.” He said he was a victim of frequent assault and profiling by the police in Nigeria. After nationwide anti-police brutality protests in October 2020 where more than 20 unarmed protestors were killed and dozens arrested, Orah decided to leave.

Last year, he arrived in Ukraine to study management at the State University of Telecommunication in Kyiv and had just finished the first semester before the war truncated his program. He now intends to enrol in a new university and continue his studies in Germany.

Orah said he has ruled out a return to Ukraine even if the war ends. “My friends are telling me that Ukrainians have threatened to beat me because I left them to fight their war without staying back to help them and that I was speaking against them on Twitter,” he said, referring to his posts about discrimination at the border.

Now in Berlin, Umuche is seeking to start a new life and forget about everything he lost to the war in Ukraine. In 2019, Umuche left Nigeria to seek a better life in Europe. As the first child in a family of five, he told me the situation back at home was not favourable to him and he had to live up to the responsibilities facing him.

“After my bachelor’s program, I knew I had to leave the country to seek better opportunities abroad because the situation at home was bad,” he said. “I have my parents, siblings and other dependents that are looking up to me and I need to take care of them.”

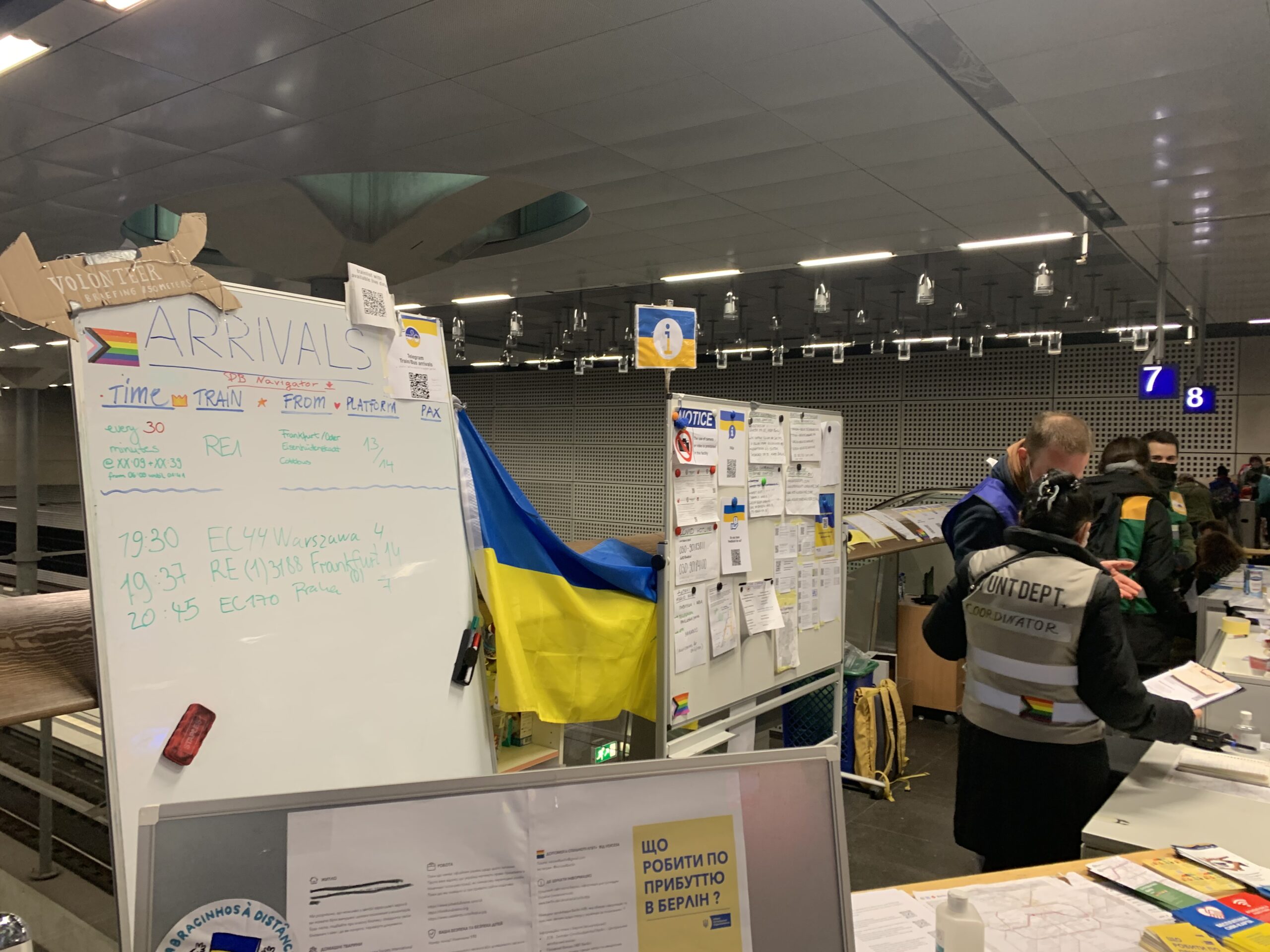

At the Union Station in Berlin where thousands of refugees from Ukraine arrive each day, Umuche is currently staying in a temporary shelter provided at the station. “War is bad,” he fumed. “A lot of people have been displaced and put in difficult situations while many more have died because of this. I hope this ends soon.”

Add a comment