BY AHMAD SAJOH

In many ways, the Anambra election presents a lot of lessons for our democracy, especially as we move towards the 2023 elections circle. Undoubtedly the build-up to the elections was filled with a lot of apprehension and sometimes fear. Drums of war beaten by separatist groups, the weaponisation of fake news on social media on the streets of Anambra created fear and confusion in the minds of the Ndi Anambra and other Nigerians.

The heavy deployment of security personnel over 50,000 in number was meant to reassure the citizens of their safety, but it also had the opposite effect of creating a scare. During the occasional exercises called ‘show of force’ in the state capital Awka, a resident was heard lamenting that an imminent clash between the separatists and security forces was sure to result in huge fatalities.

But by the time returning officer Professor Florence Obi declared results for the 21 local government areas after the Ihiala supplementary elections, the fears, apprehensions, and confusions of the build-up to the elections have become the celebration of a near successful exercise. The elections held on November 6 were to a large extent peaceful and conducted within the requirements of the electoral act. As they say in the law courts, there appeared to have been substantial compliance with the requirements of a successful election.

Advertisement

Indeed, there are many positives recorded in the Anambra elections. The most important of these positives is the reported professional conduct exhibited by the security agencies. Expectations from security personnel in the conduct of elections should be protective of voters, officials and materials, respect for human rights of all concerned and maintenance of non-partisan disposition throughout the process. According to most observer reports, the security agencies acted to a large extent within these realms. This is quite commendable.

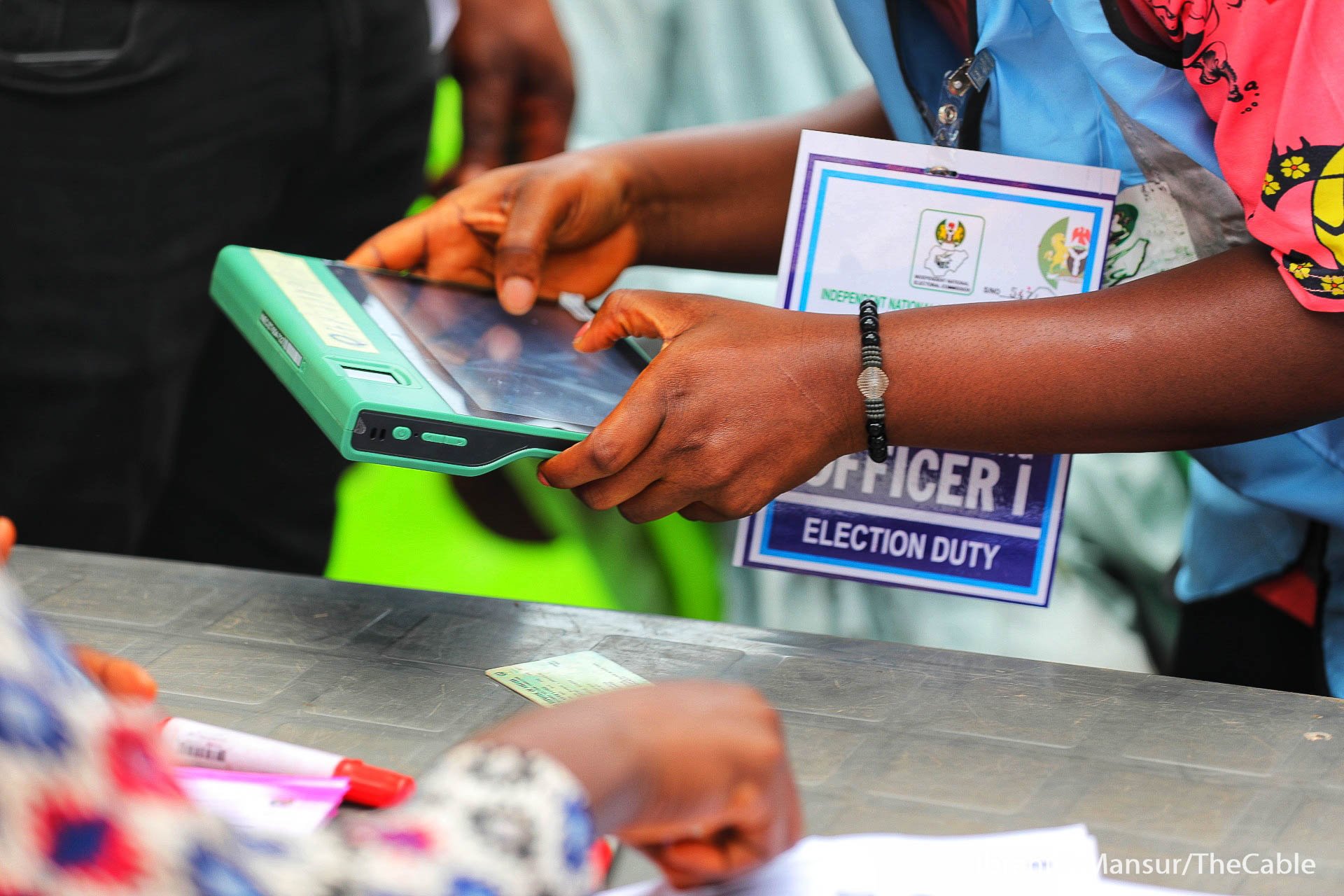

Another positive is the deployment of the bimodal voters accreditation system (BVAS). This is a welcome innovation in the electoral process. The BVAS goes a notch higher than the card reader because it authenticates voters’ fingerprints, pictures and voter details. Granted that there were glitches in a few places with respect to the effective functioning of the BVAS, it is gratifying to note that these glitches were corrected, and the process went on successfully. It must be acknowledged that the use of the BVAS indeed is a very positive development and positive step towards creating an electoral system that is credible.

INEC had also used the Anambra elections to test-run the possibility of electronic transmission of results. There was even an active results portal that could be accessed by journalists and observers during the election period. But the electronic transmission is still far from eliminating the manual transmission that requires signatures of returning officers as a legal requirement and of party agents as proofs of acceptance that the results represent voter preferences or accurate computations of the results at the collation centre.

Advertisement

The main purpose of this write-up is to speak to the numbers as expressed after the results of all 21 local governments were declared. But before interrogating the numbers, it may be expedient to try and attempt to situate it within the context of the credibility of the polls. According to YIAGA Africa, one of the observer groups that deployed over 500 observers one indication of the credibility of the polls is the confidence the contesting political parties have expressed towards the elections.

One way to gauge political party acceptance that outcomes reflect conduct at the polling unit and collection centres is by the acceptance of their agents to append their signatures to the result sheets. YIAGA Africa did a study of the numbers of party agents who signed form E.C 8A. The result shows that 86% of APC agents did sign the forms and 98% of APGA agents did the same. For the PDP, the figure is 96% and for YPP it is 79%. These are truly high figures because one returning officer for Orumba North had alleged that he signed a result sheet under duress. It wasn’t practically possible to put all the party agents under some kind of duress for this high number to sign the documents.

Talking to the numbers gives a very serious cause for concern. According to INEC, voter turnout overall was 10.12%. This is based on the fact that of the 2,466,638 registered voters in the 21 LGAs, 249,631 votes were cast in all. This is even less than the 258,334 voters accredited by 8,703 and about 10.47% of the registered voters. Even out of the 249,631 votes cast only 241,523 were valid votes. A huge chunk of 8,108 votes was invalidated. This according to INEC represents 3.3% of the total registered voters in the state. In some of the local governments, the voter turn-out was so dismally below the state average of 10.12%. Awka North had a voter turnout of 6.17%. Onitsha South is 5.99%, Idemili North is also 5.99 while Idemili South is 5.87%. The list is Ogbaru with 5.39%.

Simply put, in a state of 5,527,809 only 249,631 determined who the governor should be. Of this number, the APGA candidate polled a total of 112,229 votes, or 44.96% of the total votes cast. What percentage of the total registered voters took that decision on behalf of the rest? I cringe. A near negligible 4.55% of the registered voters took part in the decision as to who governs Anambra from 2022. For a population of 5, 527, 809, the votes received by the winner of the election simply represent 2.03%. What? So less than 3% of the population decided for everybody? Is this really democracy? Is this the rule of the majority?

Advertisement

What of the number of those who were accredited but didn’t vote? They number 8,703 or 3.49 of the total accredited voters. Although this is just 0.35% of the total registered voters, it is still instructive that even at the point of voting after being accredited over 8,000 citizens felt the whole process was not worth their while. They simply worked away. Perhaps they only went to test their voter accreditation status and no more. But all of these represent some red signals in our democracy. It speaks to the fact that the democracy project is not aligned with citizens’ interests and expectations. This is truly worrisome for the survival of our democracy even after 22 years of uninterrupted democratic practice.

There must be conscious conversations around voter apathy and voter turnout. Democracy is about the numbers and if the numbers are becoming thin by the day, then definitely something needs to do to show up these numbers. The assumption that any number that comes out to vote would validate the process just because the law says so, is totally wrong. We should be concerned. We must be concerned because of the waning confidence in the process. We must also be concerned because of the waste it creates. Imagine the wastage on the part of INEC, wasted ballot papers, wasted result sheets, and waste in many other associated materials. My brother Jide Ojo will say what happened is akin to a man who prepares dinner for 100 people and only 10 people showed up.

Are citizens passing a vote of no confidence on the whole electoral process or indeed the democracy project? If so, what could be the reason? It is very easy to dismiss the low turnout in the Anambra elections as a product of the confusion and uncertainties that preceded the vote. But that will be too simplistic. A lot more needs to be properly interrogated. And certainly, one is the increasing perception among citizens that the democratic process is not meeting citizens’ expectations. There is this growing feeling that elected officials both at the executive branch and even the legislative branch (that hinges its existence on the concept of representation) simply represent themselves and their self-centred interests rather than those of the people who constitute the reservoir from where their legitimacy flows.

The traditional definition of democracy as government of the people, by the people and for the people is mostly seen as not applicable to the Nigerian democratic situation. What many citizens I interacted with told me is that ours is a government of the few, by the few and for the few. So, it is hard to expect citizens to have confidence in the system and to actively participate in it. There is a huge trust deficit in the system and the governments that come to being consequent upon the system are seen as not representative of the aspirations of the citizens. If we do not restore trust and confidence in the system, we risk a total boycott of elections by citizens in the future.

Advertisement

Some people have argued that Nigeria should introduce compulsory voting as is the case in Australia where voting is seen as a civic responsibility rather than a civic right. Promoters of these arguments believe that voter apathy is an act of irresponsibility rather than a manifestation of mistrust in the system. But in truth, compulsory voting is an infringement of the rights of citizens. The arguments against compulsory voting include religious beliefs which is something very volatile in a country like Nigeria.

There are those who argue that in Australia, voter turnout went from 47% to 96% in 1924 when compulsory voting was introduced. It is also instructive that in a country like Bolivia where compulsory voting is enforced, civil servants are unable to receive their salaries from their banks for three months following an election unless they show proof of voting. But many countries have either repealed the compulsory voting option or left it unenforced, in Nigeria it cannot be enforced. We do not need to go this far to raise the voter turnout figures in Nigeria.

Advertisement

The only thing that can ensure adequate voter turnout is a restoration of confidence in the democratic project which includes the electoral system. One other way is to expand the latitude of the voting process through legal frameworks that allow for early voting, proxy voting and diaspora voting. Social commentators who advocate for these measures are patriots who are genuinely concerned about our elections and inclusion in our democratic process. But the game-changer is indeed the restoration of confidence in the democracy project and the elimination of the trust deficit in the governance process.

Ahmad Sajoh is the executive director/CEO FutureNow Initiative and writes from Wuse Zone 1, Abuja. Sajoh can be reached through [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment