BY OLUWASEYI OSO

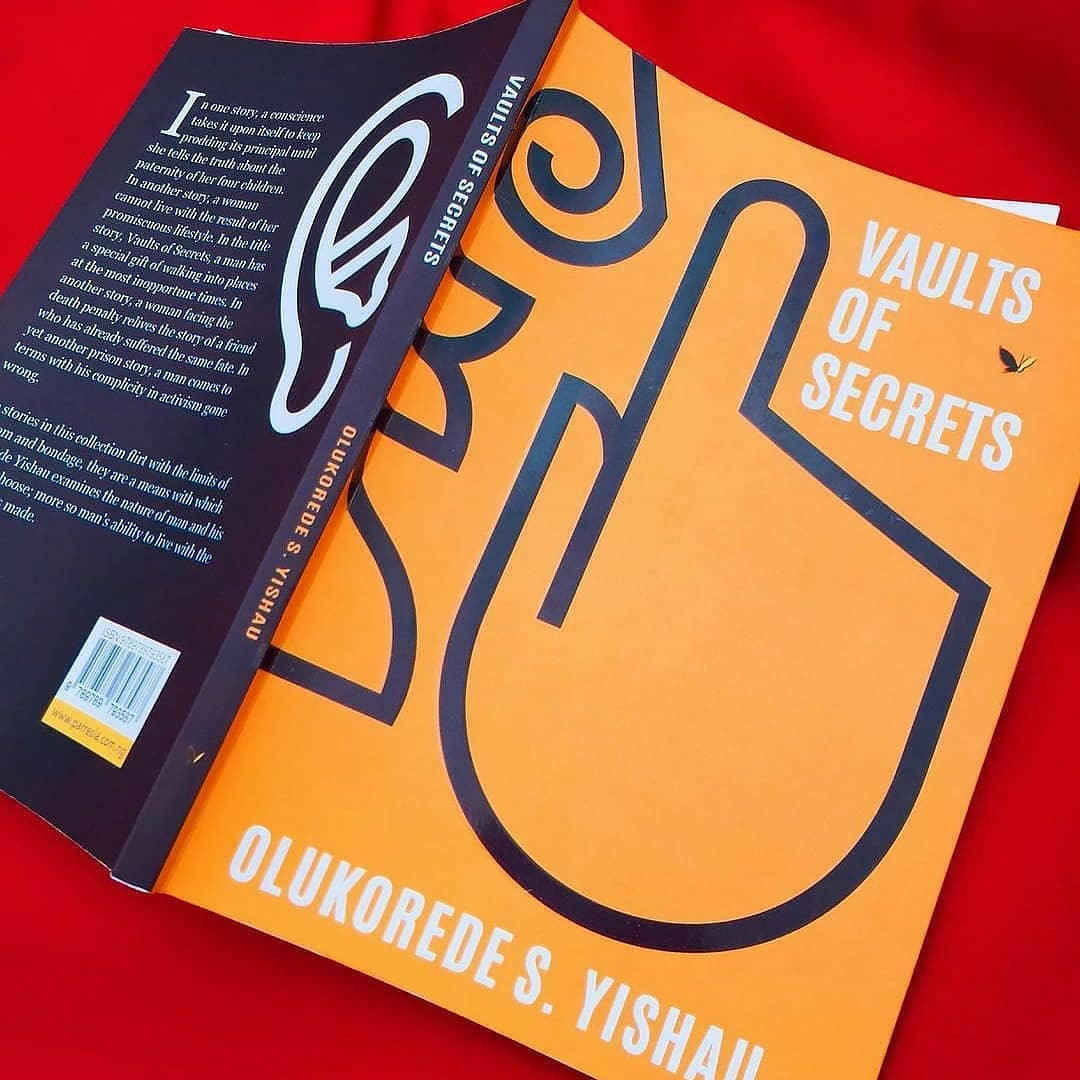

To infer that secrets are secreted from actions that societal and/or cultural constitutions do not embrace, is a fact brilliantly portrayed in Olukorede Yishau’s ‘Vaults of Secrets’.

Through the characters we fortunately meet in this collection of ten short stories, the author boldly and tellingly reintroduces the “individual as a dual being” — a dual being with two-sided identity: a private identity and the one s/he intrepidly presents before society or, say, his/her innate culture—which, at times, is not yet experienced by the individual—and the conventional culture.

It is important, as the stories apprise us, to assert that there is always a psychic drive in every human being to do what the society reprehends. Why? Every individual has an underlying evil behaviour, generated unconsciously. This is why, for instance, a fragmented society (family) creates “laws” to subjugate these underlying behaviours from pulverising the accepted modus vivendi of a society.

Advertisement

But despite the constraints of these laws, the human mind still nonconforms. And it is this weight of nonconformity that becomes the secrets—infidelity; incest; corruption; human trafficking; and more—that Yishau espouses to us through the experiential wisdom of his characters.

Religion and Politics, therefore, serve as forces that contribute to the psychosocial development of the individual. Why is this necessary—one might ask? Conjecturably, law births fate; without law there is no fate—there is no sin. Juxtaposing this ideation with the story of Oedipus Rex, a familiar reader would decipher that Oedipus would not be fated if there is no law against his action.

Insofar as growth is continual, the society always expects the individual to outgrow socially reprehensible habits and if these habits are not traduced, the society becomes a father-figure who is unwaveringly ready to punish an incorrigible son. Perhaps, this is what Freud means when he portends the theory of oedipal complex in that a male child attempts to sleep with his mother. We can suppose that the mother is the law and the society is the father that holds the law against lawbreakers.

Advertisement

Structurally, the author evidences diversity of style through distinctive use of narratologies—first person, second person, third person, epistolary, diary—just as he exposes the relativity of the human behaviour, as it were.

The narrative hook of “Till we meet to part no more” allures us to some seemly unresolved conflicts of the human nature: sexual assault, sex trafficking; domestic violence; familial dysfunction; domestic violence.

The character, Oluwakemi, whose secret and otherness is being expressed in a manner that appears like “regression therapy,” battles neurotic experiences clustered around, first and foremost, the objectification of an opposite sex by a sexually hungry 89-year-old man “in the habit of saying awful things…to touch his penis”. But her refusal does not resist his urge; and like a stubborn buyer before an enticing commodity, he offers her a hundred dollars.

We soon find out that the male nurse who rescues her—almost like Cinderella and Prince Charming—from the old man’s libido also becomes violent after she marries him. Thereafter, the persistent violence leads Oluwakemi into “akrasia” (lack of self-control) as she did something she rarely did, “I fought back” in self-defence but the society’s unwillingness to hear her truth sends her, with her fermented secrets, to prison.

Perhaps, the author opposes the Cinderellan belief of a man as a woman’s rescuer. We are also intrigued by the horrors of sex trafficking of which Oluwakemi is a victim. She is coaxed, alongside her psychically blind parents, to fall prey to Madam Koikoi’s beautiful trap. We also realise that her father abandons her mother through the drive of his crude wealth. What strikes us, nevertheless, is that the dual identity of this character is exposed in the prison as though the outside world is the real prison (of unexpressed emotions, will, ideas). The narrator of this story also gives an exposé on her otherness as she is readily ready to meet and part with death for “…causing many deaths” through manufacturing fake drugs.

Advertisement

What is more, Yishau connotes “chance” as a gift in “The Special Gift.” But this kind of gift is one which the narrator finds uneasy to gift the society. At first, the narrator burst into his neighbour’s apartment where “Idato, the house help, and Mr Essien were naked. Idato was doing reverse cowgirl and she saw me immediately I entered and shouted ‘Jesus!’”. But instead of accepting his action, he engages in what, in pschoanalysis, is termed “displacement,” which, as Tyson puts it, is the psychoanalytic name for transferring our anger with one person onto another person (usually one who won’t fight back or can’t hurt us as badly as the person with whom we are really angry) when he blames his house help and the devil. The devil is symbolic of evil in a society; thus, Essien finds a sign to justify his dual action.

One would realise that the act of infidelity is unconstitutional in a society. But despite an individual’s psychosocial construction, it is as though s/he always attempts the socially unacceptable. In this narration, we’re drawn into the secret of the narrator’s cheating brother who pleads for concealment. We are also enthralled by the sexual waywardness of Nonso, a newspaper publisher, with whom the narrator advertently finds his friend’s wife. She also pleadingly strives for secrecy but truth always has its season of triumph as Ozolua, the narrator’s friend, deciphers it for himself.

The preceding paragraph reminds us of the lubricity of life. How? Life is like a lubricant; and this is why the individual easily slips, falls; the individual plans this but does that; the individual wants this but gets the opposite. What we experience in “My mother’s father is my father” attunes our minds to the underlying nature of incest. Through a diary, William, the narrator reveals his psychically aching secret of accidentally truthing his grandfather as his father.

His unresolved conflicts come to him as dreams, typifying Jung’s supposition on—Dreams. Jung saw dreams as the psyche’s attempt to communicate important things to the individual, and he valued them highly, perhaps above all else, as a way of knowing what was really going on. William’s masked duality continues in marriage and finally, he “wonders if it’s time to reveal a part of me unknown to others.” One can suppose that William’s regression puts him into progression. Maybe the author tries to say that you need to look back to go forward.

Advertisement

Progress therapy is also evidenced as a force of salvation in “Letters From the Basement” where Nelson, a former governor, precisely jailed for corruption, indirectly extends his gloom to his family and especially his daughter who engages with a man, sixteen years older than her who “instead of telling her that he did not want the baby, deceived her that he would come to us and do the right thing. But he was secretly poisoning her to terminate the pregnancy”.

The search for solution inundates Nelson’s mind with regret while his wife’s search for solution almost puts her in a false prophet’s snare. Nelson repeatedly persuades her to get rid of the idea of freedom through a money-thirsty prophet. Ultimately, Nelson sees progression as the key to freedom from his revealed dual identity: “What mattered was that my progeny would live on, and tomorrow would be better for them. My life, I thought, would have ended well.”

Advertisement

‘Youing’ the reader in “This Thing Called Love”—where a formerly devoted father and lover abandons his family for another woman, secretly; whereas the narrator, also with a secret, is innocently jailed—convinces the reader to see love as a portal of salvation and resuscitation. Here, “your emotions oscillated between pity for a father on the wheelchair, and anger for a father who left the familiarity and security of your home for the novelty of a strange woman’s thighs (50).”

A reader is convinced of the war between the two forces of human nature—love and strife—as an individual battles endlessly with these forces. Conversely, the author prescribes an antidote to the reader for self-healing and reconnection—love; loving again. Also, in this story, we discover that the untold hidden truth of the narrator, Jacinta, finally sets her free from her unheard truth and unverified imprisonment.

Advertisement

“Open Wound,” “Better than the devil” and “Otapiapia” give an insight into the phenomenology of conscience as an indefinite side of the human being. The conscience can be manipulated to do right or wrong; to seek and to hate what you find. In, “Otapiapia,” an exposed cheating wife commits suicide because she cannot live with AIDS. In “Better than the devil” the narrator decides to end the evils attached to cultism but his mind is still persuaded to see the socially wrong as right. These crystallise the unstable duality of the individual.

Every human being is a pursuer of a lost other. Why? We are not complete until we get want we want in time. But, at times, it is impossible to find one’s truth. This is what Yishau does with “When Truth Dies” and “Lydia’s world,” as one character struggles to unfurl her supposedly dead husband whilst another character, Lydia, realises that her switched-at-birth true child is now dead. The writer creates the image of the “will o’ the wisp here—a delusionary or otherwise unachievable goal that one feels compelled to pursue. What you desire may not desire you.

Advertisement

In conclusion, acceptably, your personal constitution of right and wrong evaluates and judges a person’s behaviour; but unless you can see yourself experiencing the same, you might not understand the evasiveness of the human nature.

Once a secret is hatched, the society—like the illustration at the rear of this book—is quick to hear without, sometimes, digesting. Whereas, many among the audiences of this open secrets or open wounds have their secrets, too. Yishau entrusts, through this book, the secret and duality of individuality to his reader(s); and this review, therefore, is a contribution to the idea of the human complexity as it has been characterised in this book.