Army chief, Lt. Gen. Ibrahim Attahiru, has said that the Nigerian Army “will remain resolute in dealing with the prevailing security threats across the country in line with President Muhammadu Buhari’s directive.” Attahiru emphatically said that the army is committed to implementing Mr Buhari’s marching orders to decisively deal with all security challenges facing the country.

Most Nigerians would respond in one of two ways: a thumbs up or to go into “siddon look” mode. But that should not be. The army chief’s statement not just speaks to the kind of training our military officers have been receiving, but also to the institutional rot that has led to a lack of direction in this country.

Once a precedent has been set, it is very difficult to break. Deploying the military in 1962 to quell what the Balewa government referred to as the “Tiv Riots” was a terrible idea and successive governments have continued this pattern, eschewing conventional conflict resolution mechanisms that involve dialogue and coalition building, necessities in a multinational state like Nigeria. The army does not–for important emphasis–have any business other than border and territorial defence. But Nigerians have so been imbued with the culture of brute force such that we see military deployments in internal security crises as normal.

But it is very much understandable that General Attahiru needs to show workings–verbally and otherwise.

Advertisement

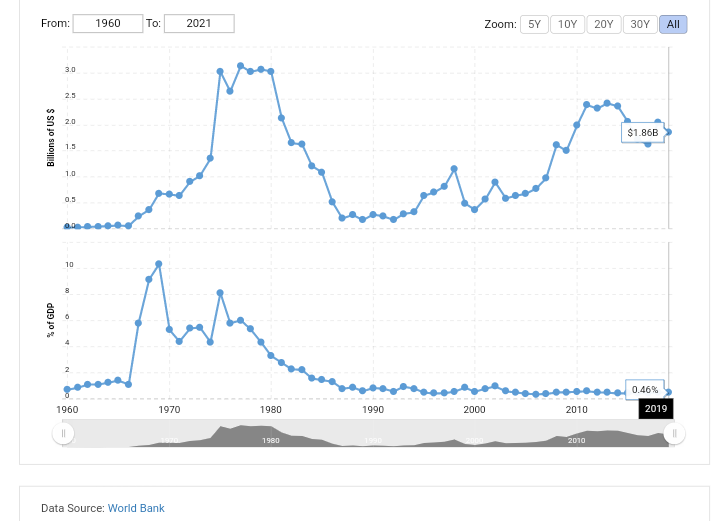

This chart shows Nigeria’s defence budgets since 1960 and you can see how much it has spiked since the Boko Haram insurgency intensified. The only other country in Africa who outspends Nigeria in that category, is Egypt with at least $3 billion budgeted annually for defence, as against Nigeria’s $1.6 billion budgeted for the defence ministry in 2020. In the midst of an allegation of missing funds by the NSA after a jump in defence spending, the primary focus should be on how to account for those funds. Not try to justify them by chasing red herrings.

The marching orders by both the president and the army chief are reckless, as they basically give the army carte blanche to use brute force to deal with security threats that require minimal application of force. Turf wars and clashes between various youth gangs are a national headache. That’s a given. What the solution should be, is not the deployment of the military to arrest “cult boys” after every clash.

Advertisement

How many cult boys can the military actually arrest.

To buttress this point further, I will draw on the vicious cycle that was my experience during my time as an undergraduate in the University of Benin. The university is notorious for being a centre of youth gang-related violence that often spills into Benin City. An uprising would happen in the dreaded Ekosodin community–the spiritual headquarters of such brawls–the university management would get agitated from calls by the community leaders, threatening to throw out students residing there. The university would call on the government to intervene. The state security service (or DSS) would deploy some of its field operatives to keep the peace, ensuring calm at the sight of stern looking agents with big guns. After a few days, the operatives would leave and the violence would return. Rinse, repeat. I graduated a few years ago and nothing has changed till date.

The story is virtually the same in other places. Force has been applied to quell the spate of protests in Abuja by the Islamic Movement of Nigeria looking to get the government to release its leader Ibrahim El Zakzakky who has been in detention for years. Almost every time the Shiites protest in Abuja, the police resort to the use of force which has only emboldened the protesters after a large number of their members have been killed.

Advertisement

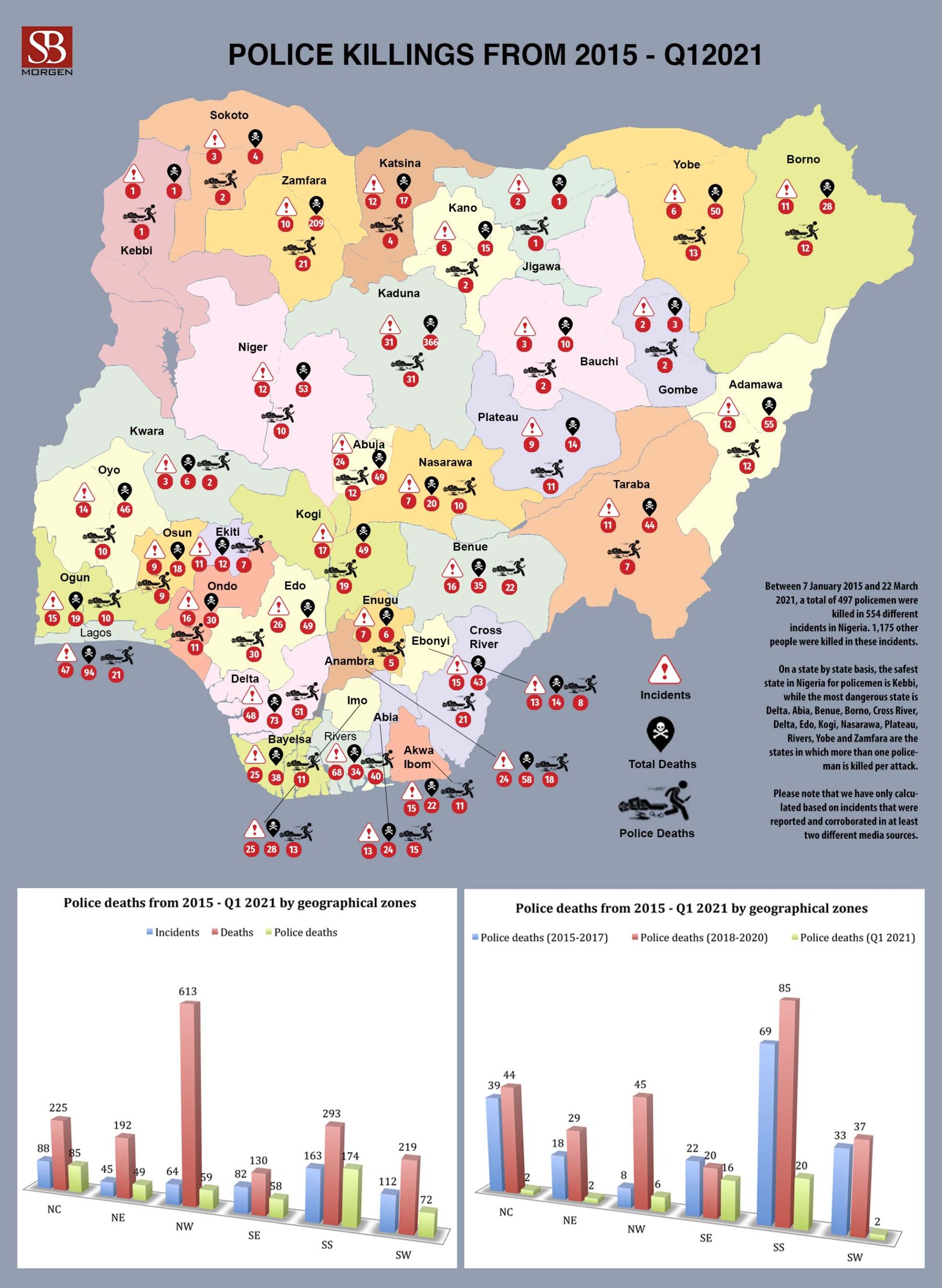

Simply put, the militarisation of security is fuelling insecurity in Nigeria, especially because resentment over unpunished state sponsored abuse is hardening sentiments against the state, making its security agents the victims of its own mistakes. It is also a partial explanation for an increase in the number of incidents targeting police officers across the country, especially in the South South and South East regions.

There is a pressing need to reinvigorate other branches of law enforcement and security in Nigeria . Too often, political leaders authorise the deployment of military force as quick fixes to problems better solved by the long term application of legal, political, and social interventions, or other avenues of conflict resolution. These military deployments have lacked oversight and often resulted in human rights violations against Nigerians living in the crisis areas, as exemplified by the fact that the number of Nigerians killed at the hands of security agencies at the beginning of the pandemic induced lockdown in 2020 was greater than the number of people killed by the coronavirus itself as of middle of April.

The army needs to set its priorities straight. It is not the ministry of interior charged with internal security. It is not the police force. It is not a policy making agency tasked with making political statements that border on campaign promises. It’s focus should be on prosecuting the insurgency in the North East, the welfare of its officers in the war theatre protesting for not being paid salaries, as well as finding ways to reduce corruption within its administrative departments. We need to be serious in this country.

Macharry is an analyst at SBM Intelligence

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment