BY OLAYIWOLA ADENIJI

Permit me to start by congratulating our celebrant of today; not just because he has hit the milestone year of 50 in a country where life has become such a cheap commodity. What is significant for me is the manner in which he has decided to mark the day – a conversation to address some of the issues that confront our nation and also a public presentation of this collection of short stories aptly titled; The Law is an Ass. For those of us who know the author so well, and I dare say, I do, this does not come as a surprise. He takes Nigeria too seriously (apologies to Odia Ofeimun!)

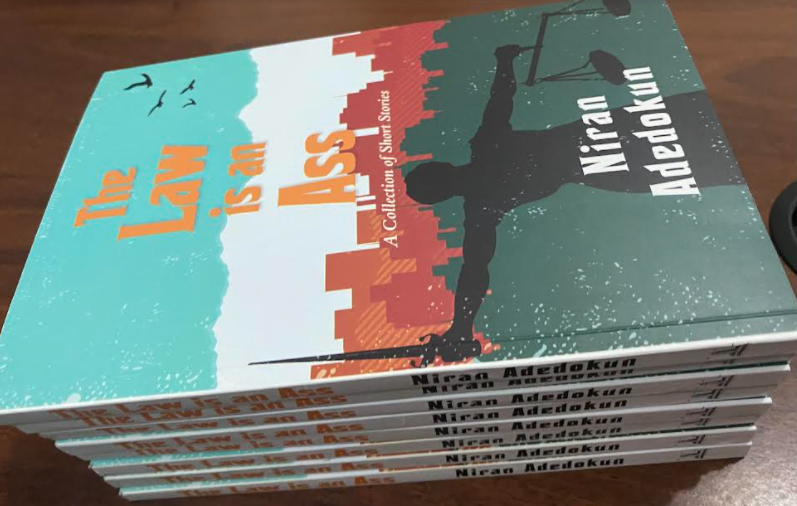

My task is simple – to interrogate this collection of nine (9) short stories and either convince you to buy it or use your hard-earned naira on something more profitable. By inclination though, the former will be my preference. After all, I have spent a good part of my adult life canvassing the position that a writer should be able to live off his craft. I hope by the end of this exercise, I would have whetted your appetite enough to buy the book not only for yourselves but also for your friends. Let me make a confession though. I admire authors of short stories because of the discipline required to make the stories concise and compelling in not too many words. I also love reading short stories because they have a way of imparting knowledge in a structured and predictable way but I struggle in reviewing short stories because you have to deal with varied themes, and style in a ‘structured’ narrative, therefore, suffering as much pain as the author yet the reviewer or critic as the case may be, only gets a footnote mention in the life of the book. But then, all of these are my own pains. Niran called and I had to answer.

As stated earlier, this collection deals with varied themes from the rather mundane to the serious, hope and deferred expectations, love and hate and other conflicts and absurdities in our society. In each of the stories, the reader finds someone to cheer on or someone to hate as the author navigates the labyrinth of life and living in urban Nigeria. Though an easy-to-read collection, the stories are thought-provoking and engrossing. In his own unique way, the author is able to hold the interest of the reader. In terms of craft, some of the stories are more accomplished than others. This should be expected. No two works can be adjudged to be of the same quality or standard.

Advertisement

In Dubai with Love, started out like the proverbial grass to grace story as everything points to Ladi overcoming the pains of an indigent childhood to become a successful and happily married banker until the dramatic twist when he loses his job. Ladi might have failed to make hay when his sun shone- to parody the popular idiomatic expression, there is no explanation for the unkindest cut by the closest people to him. Unfortunately, like all good stories, the author leaves the rest for the imagination of the reader.

In terms of thematic preoccupation, Right from the Cradle is not too different from Dubai with Love. It is also about the betrayal of trust as Daniel exploits his economic advantage over the family of Engr. Oyide. Thinking that Oyide will seek justice for his daughter and protect the dignity of his family, he does the unimaginable. Clearly, demand for ransom is not the exclusive preserve of kidnappers or bandits as it has become convenient for us to refer to these criminals.

One of the stories in the collection that I could be caught reading, again and again, is Just like a Flash, set in the fictive Olokoode (this is not accented so difficult to know what the right pronunciation is) community, one of the many shanties in cosmopolitan Lagos, which Toni Kan aptly describes as the Carnivorous City. Predictably, this community is all about crime, prostitution, sorrows, tears, and blood as seen through the experiences of the two major characters who as a result of contrasting fortunes, find themselves in the ‘dungeon’. In the end, Benita, who finds herself in Olokoode as part of a survival strategy having lost her dad and is determined to complete her university education, is able to fulfill her dream. The story of Halima, the archetypal ghetto girl, is however different. She runs to Lagos for fear that she had killed her brother who had caught her trying to steal their father’s money to help an indigent friend at school. The omniscient narrator skillfully drops that for the reader to make his judgement.

Advertisement

The police will again be the focus in The Money or the Child where the author addresses not just the issue of corruption but a soulless society where human lives become inconsequential because of the craze for wealth. The once innocent and brilliant Kehinde joins the police and immediately sells his heart to the devil. Even the irredeemably corrupt senior police officer is shocked when the ‘innocent Kehinde’ suggests that they should leave an accident scene. This same theme is echoed in The Drive except that in this instance, the perpetrators are the notorious Area Boys who are more concerned with whatever they can get from the misfortune of other people.

The Fourth Estate will not escape the creative and critical lens of the author. The story aptly titled Devil’s Table captures a growing concern by watchers of the Nigerian media especially as members of the political class continue to devise creative means of compromising some critical section of the media under the guise of helping to facilitate their work. It is a call for the members of the Fourth Estate to maintain a sense of vulnerability in their dealings and engagements with the political class. The relationship starts with mere acquaintance or ‘consultancy’ and then grows into arranged project tours and finally, political appointments and the attendant sweet smell of lucre. The highly critical Stanley thinks he is beyond reproach. He honors a ‘harmless’ invitation from the governor. Soon he is trapped. The governor knows he needs money to take care of himself and his ailing mother, “the only meaningful thing in his life apart from his job which didn’t even pay well…” The rest, as they say, is history.

Recently, I read Michael Prodger’s review of “Keeping an Eye Open: Essays on Art” by Julian Barnes and Michael Craig Martin’s “On Being an Artist” in a 2015 edition of the UK edition of New Statesman. His preoccupation was on how art rarely floats free of biography -or autobiography for that matter. And this age-long contention in literary theory and practice comes to mind when reading The Law is an Ass, which is the title story of this collection. Being a legal practitioner (in his spare time?), the contention here is between the radical school of thought and the liberal school of thought in legal practice. How much of this reflects where the author stands on the divide? The more I read this story, the more I asked the question and this is largely due to his treatment of the radical Barrister Alade who from the beginning faces a headwind- an unwinnable case. Though described as brilliant, he is said to have two tragic flaws – “an uncompromising spirit premised on self-confidence and an obstinate lack of empathy”. Nothing wrong with being self-confident, but a lawyer without empathy is in the wrong profession. The author leaves Alade with no redeeming quality, even the so-called brilliance is absent in all his submissions. Is this normal in legal practice or even normal life? Couldn’t he smell the coffee? Why create a near-static character in your protagonist when the story does not seem driven by the plot?

In terms of craft, the most accomplished of the collection is Once Upon a Night. In this story, the author deploys the use of flashback, reverie, and suspense to a hilt. It is one story with the “Oh My God” reaction. This has all the ingredients of a good story in terms of characterisation, setting plot, conflict, and resolution to keep the story and action to develop in a logical way that the reader can follow. Phillips, the protagonist, is struggling with his marriage to Ada because he feels that his wife isn’t showing him enough affection and at the prompting of his friends led by Jide, decides to explore having extramarital affairs.

Advertisement

The Voice is deep (in the symbolic sense) and it can be analysed from different perspectives. It deceptively reads like a simple story but raises so many questions. It will be interesting to hear from the author the inspiration behind this tragic story of young Azeza Usman who loses her soldier-father in an accident. As a result, she loses the zest for life. She fails out of school and the relationship with her mum becomes very complicated as it is difficult for the reader to understand why she will not outgrow the pains of loss and move on with life. The story raises more questions than answers. Isn’t the relationship between Azeza and her dad another implied instance of what is called Electra complex in psychoanalysis? Yes, society probably has its own share of the blame. Why do we spiritualise issues of mental health instead of treating for what it is- a medical condition?

In The Drive, which is the last story in the collection, there is another preoccupation even if subtle, with the issue of mental health. The difference here is that the cabman (Franklin) discharges his passenger before things got out of hand and that is the last we hear of him in the story except for the occasional reference to him by Yemisi. This is more about a love story gone south – no thanks to the ill of ethnic profiling that has bedeviled the society. Young lovers cannot get married because of mundane issues as tribe or religion. The Drive was meant to be a metaphor for what in literature is referred to as a journey motif, an adventure leading to some sort of self-realisation. The reader however gets a shocker at the end.

Without a doubt, Niran Adedokun’s The Law is an Ass makes an interesting reading with stories that capture the imagination of the reader. The stories provide us a mirror, which highlights and interrogates our tensions, fears, and aspirations as a people. Though not overtly prescriptive, he has through the characters and plots in these stories provided a beacon light to guide us to find the right path. The composite influence of a dramatist, social commentator, journalist, and legal practitioner is very apparent in this collection. For a first time out as a fiction writer, he has demonstrated an appreciable mastery of his craft. Of course, there are opportunities for making the language a lot tighter. One area to look at in subsequent editions is in the handling of setting as a vital part of storytelling, which helps to establish the mood, reveal characters and conflicts, and provide clues to the thematic focus. I am sure you will all find this book as interesting as I did. It is highly recommended.

Olayiwola sent this review in from Texas, United States of America

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment