BY UGOJI EGBUJO

The Pandora Papers are out. Startling revelations are seeping out. Some saints have been demystified. The list includes Uhuru Kenyatta and about ten Nigerians. The use of shell companies in tax havens to mask the ownership of offshore companies and hide illicit wealth is troubling. Bagudu, Peter Obi, Stella Oduah, Tinubu, Oyetola are household names on the list. But what about Mohammed Bello-Koko, the acting managing director of the Nigerian Ports Authority (NPA)? How did he get there?

Nigerian politicians call every investigation that affects them a witch hunt. But there are allegations that the power tussle in the NPA has not abated. Yet the work of a consortium of 600 journalists cannot be easily impeached as a vendetta. Since Bello-Koko’s case has generated interest, a comprehensive appraisal of the Premium Times report and testimonies of his former colleagues has become imperative.

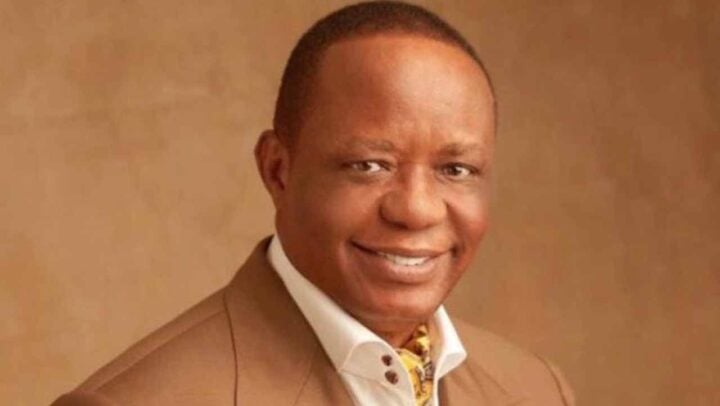

In 2008, Mohammed Bello-Koko was a management staff of Zenith Bank. Young and enterprising. While growing in banking, FSB and Zenith Banks, he invested his earnings into the cement, telecoms and equipment leasing businesses and created jobs. Like many other senior executives of the new generation banks, with blossoming alternative income streams, he saved for the future in real estate assets. Mohammed Bello-Koko had a reputation for being industrious and prudent.

Advertisement

The economy of the United Kingdom, 2008-2012, was comparatively stable. Other Nigerians with means or access to mortgages also bought UK properties. Dependable as UK properties were, the UK property sales and capital gains taxes were prohibitive. Good bankers are shrewd. To facilitate a profitable engagement in UK real estate market, Mohammed Bello-Koko incorporated two companies in the tax-friendly British Virgin Islands (BVI) in 2008. Then, he was neither a governor nor a minister. Then, he was neither a politician nor a public servant.

His motives, evidently, were ease of business and legitimate profit maximisation. The BVI shell companies didn’t trade. So they couldn’t have been conceived to siphon and stash away government treasury funds. The absence of ulterior motive was evident in the fact of his transparency which many of the other implicated persons lacked. He didn’t hide his ownership of the companies. Investigations showed that Marney Ltd. and Coulwood Ltd. were not trading companies. There is not a shred of evidence they were vehicles for money laundering.

So what is Mohammed Bello-Koko’s offence?

Advertisement

Buying an asset through a mortgage in a foreign country with one’s hard-earned money as part contribution offends neither God nor man. The lawful purchase of assets in a foreign land through a shell company registered in a tax-friendly nation is smart business. A savvy British bishop seeking to invest in the Nigerian real estate market would, in all likelihood, seek to pay the least possible taxes. Many respected UK politicians and business leaders own shell companies in offshore tax-friendly countries.

So what exactly is Mohammed Bello-Koko’s sin?

He didn’t hire faceless nominal directors. He wasn’t a politically exposed person in 2008-2013 when he purchased the assets. He didn’t employ a multilayered murky mechanism to obscure his ownership of foreign property. How can the transparent ownership of United Kingdom assets through a legal British virgin island entity by a young hardworking Nigerian not be praiseworthy? With the two BVI vehicles, he retained the easy lawful capacity to maximise his profit and repatriate his wealth. The potential to dispose of the properties by simply selling the shares of the offshore companies couldn’t have breached any ethical, let alone, legal standards.

Nevertheless, the authors of the Pandora Papers must be commended. The over 600 journalists that sifted through millions of papers did a wonder watchdog job. The Pandora Papers, like the Paradise and Panama Papers before it, would help curb secrecy and corruption, especially in Africa. Unfortunately, when such broad-brush investigative jobs are done, a few innocent people could be touched. Perhaps, for this reason, the authors left the caveat that the incorporation of a shell company to transact a business isn’t always wrong. Should they have been a bit more discriminating, more diligent?

Advertisement

Did Mohammed Bello Koko purchase a property in UK after the assumption of office as a public servant?

Mohammed Bello-Koko acquired four of the named UK assets between 2009 and 2012, while he was an ordinary citizen. Those he didn’t fund through mortgages, he bought with hard-earned money. The total amount of about N250 million involved in the purchase of these houses included a mortgage loan from First Bank UK. The fifth property which the Pandora Papers erroneously claimed was purchased in 2017 is an apartment in the decommissioned Battersea power station, London. The Battersea luxury apartments were sold by open bidding. A much sought-after property with an initial completion date of February 2015, whose purchase agreement Bello-Koko had entered into more than three years before assuming public office, in 2016. The completion date was shifted thrice. If there hadn’t been any delays, the balance payment for the purchase would have been completed before Bello-Koko assumed public office. When it was ready in 2017, Mrs Bello-Koko, director of Coulwood, sold one of their properties to raise funds to finance a mortgage for the balance payment of the Battersea property. Were the Bello-Kokos expected to forfeit the property and the part-payment of over a hundred thousand pounds simply because Mohammed Bello-Koko became a director in the NPA? The Premium Times’s assertion that he secretly acquired the fifth property after becoming a public official is a grossly misleading half-truth.

Did Mohammed Bello-Koko breach CCB rules?

The idea that he purchased a house in the UK while a director of NPA might sound tantalising, but the facts speak differently. The suspicion that he remained director of the BVI shell companies while functioning as a public servant is correct. In 2016, before the assumption of office as director of the Nigerian Ports Authority, NPA, Bello-Koko resigned directorships of all companies, including those of Marney Ltd. and Coulwood Ltd. On assumption of public office, he declared his assets including the offshore vehicles and British assets, as required by law. Perhaps if the authors of Pandora Papers had fuller information, their conclusion might have been different.

Advertisement

Mohammed Bello-Koko, former colleagues say, is godfearing and disciplined. In private and public lives, integrity and efficiency have been his motto. Shell companies are frequently used to conceal assets bought with stolen funds, but in Bello-Koko’s case, they were most probably used for legitimate purposes. There is nothing in the Pandora Papers that even suggests he broke any rules. If the authors had paid a little attention to details and dates, they would have avoided the mistake of the inclusion of the name of a nobleman in an ignoble list.

Ugoji Egbujo can be reached via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment