Sachet water factory

Residents of many communities in Lagos state struggle to get potable water. Aside from spending money, the search for water has also led to lifestyle changes as some residents have to wake up at midnight or stay up late to use the wells when others are asleep. All over Lagos, residents are trying to find solutions to water scarcity at different levels, and Lekki, one of the most developed areas in the state, is not exempted. In this second and final part of documenting the state’s water woes, TheCable’s DESMOND OKON and VICTOR EJECHI examine the government’s effort to keep the pipes running amid poor funding.

When it comes to finding good water, residents in Ketu, Ojota, and Ikorodu pretty much share the same horrid experiences. But the situation is worse in places like Irawo, Ikorodu, where there is no sign of a water corporation servicing the area, and also no access to boreholes – not even the ones provided by neighbours or landlords as obtained in other places.

Here, residents rely on rainfall, and meruwa, small-scale vendors, for their water needs.

When these options are not available, they turn to wells, mostly unclean, and water stored in a shallow “well” whose source is the Ogun River when it overflows its bank following the opening of the Oyun dam.

Advertisement

Mujidat, who resides in the area, said it has become very difficult to get potable water as prices have continued to soar. It gets worse during the dry season when the wells get dry.

“For cooking and drinking, we buy water. We don’t have access to boreholes,” Mujidat said.

“It’s always difficult for us to get drinking water sometimes if we don’t buy, unless it rains. 25 litres is N150. During the dry season, it’s always difficult for us to get water.”

Advertisement

An 8.03km drive from Irawo leads to Aruna Bus Stop, a stone’s throw from Nosa Osemwegie’s house. A water corporation outlet exists at this bus stop. But residents do not benefit from it; they rely on wells and boreholes provided by landlords.

Osemwegie, a 28-year-old business analyst, said access to water is easy and he hardly spends on it.

“Accessing water in my environment has been quite seamless because my house has a borehole,” he said.

However, difficulty sets in when there is a prolonged power outage which forces residents to look for water from nearby wells. Osemwegie added that in his four years of stay in Ikorodu, water has never been accessed via public pipelines.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, following a visit to the water corporation in Aruna, TheCable learnt that the facility had stopped producing water for over six months. The security personnel who spoke to the journalists did not give reasons for this, but he referred the team to the corporation’s head office in Ijora.

LEKKI RESIDENTS RELY ON PURIFIERS, SACHET WATER

Unarguably, Lekki houses some of the most influential and affluent Nigerians, and also the Dangote Refinery and the deepsea port — Nigeria’s hope out of a resoundingly struggling economy.

Panache lives here. Babajide Sanwo-Olu, the state governor, once described Lekki as the “highest developed real estate sector in the whole of Africa.”

Advertisement

But judging by basic amenities like potable water supply, Lekki and Agboyi, a downscale community, can be placed on the same pedestal.

“You can only use the water here to clean stuff. For some people, I’ve heard that the water reacts to their skin,” said Israel Ibrahim.

Advertisement

Ibrahim, a creative director in a hospitality firm, had lived in two places in Lekki since he relocated to Lagos from Benue state. In spite of the luxury exuding from his area, he goes home to dirty water as access to potable water still remains a mirage.

Stressing that he does not have access to public water too (that is, from the water corporation), he admitted that the borehole provided by his landlord is manageable, except for cooking.

Advertisement

“So, the alternative for me to cook is to get bags of pure water — six bags — that will be N1,200 in a month,” Ibrahim said.

Tolani Oladesu said in the three years she spent in her former house in Osapa London, “no drop of water came from the tap”.

Advertisement

Oladesu said she bought water for everything: to cook, bathe, wash and flush despite living in a very expensive apartment.

“It was not a cheap apartment. Neither did the owner consider that in his fees,” Oladesu said, recounting her ordeal in three locations in Lekki.

“From there to another on Ado Road. Same amount, but here at least we see brownish water we could use to flush. The caretaker said the other blocks had better water but if you went downstairs, the water was a bit cleaner. We lived on the first floor, so we had to fetch water from downstairs to flush and clean the house. But to cook and wash, we bought water.

“Scenario three, still in Ajah: Another house, water flows from the tap, much cleaner. We use filters for the tank and in the kitchen tap. But we still buy water to cook. We are constantly changing filters here to keep the water clean and also wash the tank in between.”

This is the zeitgeist in Lekki.

TheCable learnt that in most places, homeowners provide boreholes for themselves and tenants. But the real challenge is getting clean and potable water.

From interviews conducted, those who have drilled boreholes for themselves spend money on installing purifiers to get the quality to a reasonably usable standard. Others, who do not have the wherewithal, manually introduce chemical purifiers to their tanks.

For example, nearly every home in Lekki Gardens Phase five has a purifier installed in their water tanks. “If this is not done, the water that comes out from the borehole stinks,” said Tochukwu Chidimma, a Lekki Phase One resident.

“It just smells literally from the tap,” Chidinma added.

But even with the purifiers, it is still not drinkable, and cannot be used for making food. So, residents are, therefore, forced to buy water from various sources, including tankers.

“I use water from the dispenser if I have to cook maybe soup or something that requires significant water,” Chidimma noted.

She said a bottle of dispenser water costs N1,000 and it could last for two weeks. If she uses two bottles every month, that amounts to a N24,000 annual bill for the water dispenser. While spending a lot of money on water has become normal in Lekki, some facility managers are affected more as they have to buy water from tankers at about N2 million for their tenants, a source said.

RAIN, A BLESSING FROM GOD TO AJEGUNLE DWELLERS

For the people of Ajegunle, a community in Ajeromi Ifelodun LGA of Lagos, the rainy season is a huge blessing from God. This is because it is the only time they spend less on water. Describing life in the community without access to good water, Shola Nelson, a 31-year-old man, said it has been challenging having to buy water daily.

Nelson, who said he was born and bred in Ajegunle, spends over N4,200 a week just to have access to good water.

“In a day, my siblings and I need like three kegs of water, and that cost about N600. It has been telling on me because it’s not every time I have enough money to buy water. We even have to literally ration water because of the cost.”

“The rainy season is the most exciting season for most of us living in this community, especially those that sell food and go to work. When it rains, we fetch water and make sure we have every single bucket in the house filled with water. We even have tanks to store rainwater.”

REGRETS IN FESTAC, SLEEPLESS NIGHTS IN SURULERE

Elsewhere in Festac, some residents are wallowing in regret for relocating to the town owing to the poor quality of water in the area. Juris Chukwudi’s life began to quickly ebb away when he arrived at Ago Palace (Festac) in Oshodi Isolo LGA and found himself using dirty water.

After some time, Chukwudi, 27, developed a dermatological problem which he claimed was due to constant usage of unclean water. This marked the beginning of his daily spending on alternative water supply. An auto mechanic, Chukwudi told TheCable that the amount he now spends on water has wreaked havoc on his finances.

“Not only was the water causing damage to my skin, but when it was used for laundry, the clothes literally started fading. To avoid such an issue, we have to buy water. This is the community I have been living in for the past four years and the issue has always been the same — no clean water,” he said.

“We resorted to buying water from meruwa guys. I pay N2,000 for 10 kegs of water which will only last me for a week. That’s if I’m lucky. Financially, it is not working for me. There are periods when the business will be slow and there is little cash at hand. I will just use the available water because I don’t have a choice.”

Anita Philips, who also lives in the community, said she agreed to a monthly water supply package with a meruwa operator to enjoy a discount. Instead of spending N8,000 a month for 40 kegs of water, she pays N7,000.

“Generally, most houses in Ago Palace and some parts of Festac don’t have access to clean water,” she said.

Meanwhile, in some parts of Aguda in Surulere, the search for water is leading to poor sleep patterns for residents. TheCable learnt that if you wake up around 6 am, the chances of getting water on time to enable you to prepare for work are slim.

Biola Afolabi said residents wake up very early to look for water. When they find a source, they would queue up immediately. This is because water is generally unavailable in the area.

“Anyone that wakes up late will probably wait till evening again when water might be available from the suppliers. Sometimes, with your money, you won’t still have water,” Afolabi said.

A REFLECTION OF NIGERIA’S WATER CRISIS

What is being witnessed in Lagos mirrors the inefficiencies in Nigeria’s water sector. Peter Hawkins, UNICEF representative in Nigeria, said Nigeria is going backward on access to clean water. From a health perspective, Hawkins said only six percent of primary healthcare centres across the country have access to clean water.

He argues that Nigeria has to look at different ways of capturing water, and making water available, especially in the urban areas — but that will require considerable investment.

“The level of investment I think, if I remember correctly, is between the region of N3 billion a year if Nigeria were to catch up with any sort of reasonable level of access to clean water and good sanitation,” Hawkins said.

“If it doesn’t take place, I am afraid, over the next 20, 30 years, Nigeria will be faced with serious consequences.”

Meanwhile, data from BudgIT, a civil society organisation, shows that Nigeria’s allocation to water resources for 2022 stood at N174.24 billion. Of this amount, the federal ministry of water resources headquarters got the highest allocation of N77.53 billion, while the lowest — N1.09 billion — was earmarked to the Nigeria Hydrological Service Agency.

GOVERNMENT UNDERFUNDING WATER PROJECTS… WHAT NEXT?

The Lagos state water supply master plan puts the daily water demand in the city at 540 million gallons per day (MGD) but production by the Lagos Water Corporation (LWC) stands at 210 MGD. By implication, there is a deficit of over 300 MGD, which translates to around 40 percent access to clean, and safe water, according to the state government.

Nonetheless, the government through the Lagos State Water Regulatory Commission (LASWARCO) plans to regulate water providers in the state.

“The commission is also statutorily empowered to regulate activities relating to abstraction, provision, consumption, production, supply, distribution, sale and use of water, the quality of service and the tariff payable to ensure the financial stability of the water sector and regulate allowable returns to the operators, be it public or private water service provision,” Funke Adepoju, executive secretary of LASWARCO, said.

The first sign that easy access to water in Lagos may be a hopeless venture for a long time is the lifeless fountain at the entrance of the water corporation’s headquarters in Ijora. The dry fountain gives a broader view of the water crisis in the city.

Muminu Badmus, the managing director of LWC, told TheCable that the water crisis in some parts of the state is a result of some uncompleted projects that the corporation is currently working on, but stalled due to funding setbacks.

Checks by TheCable Index show that in the last six years, the Lagos government has sustained its budgetary allocation to the corporation in huge sums.

In the state’s 2017 budget, LWC got N1.606 billion. It received N1.958 billion in 2018 and N3.208 billion in 2019.

LWC got N2.754 billion, N1.764 billion, and N940.0 billion in 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively – totalling about N12.223 billion.

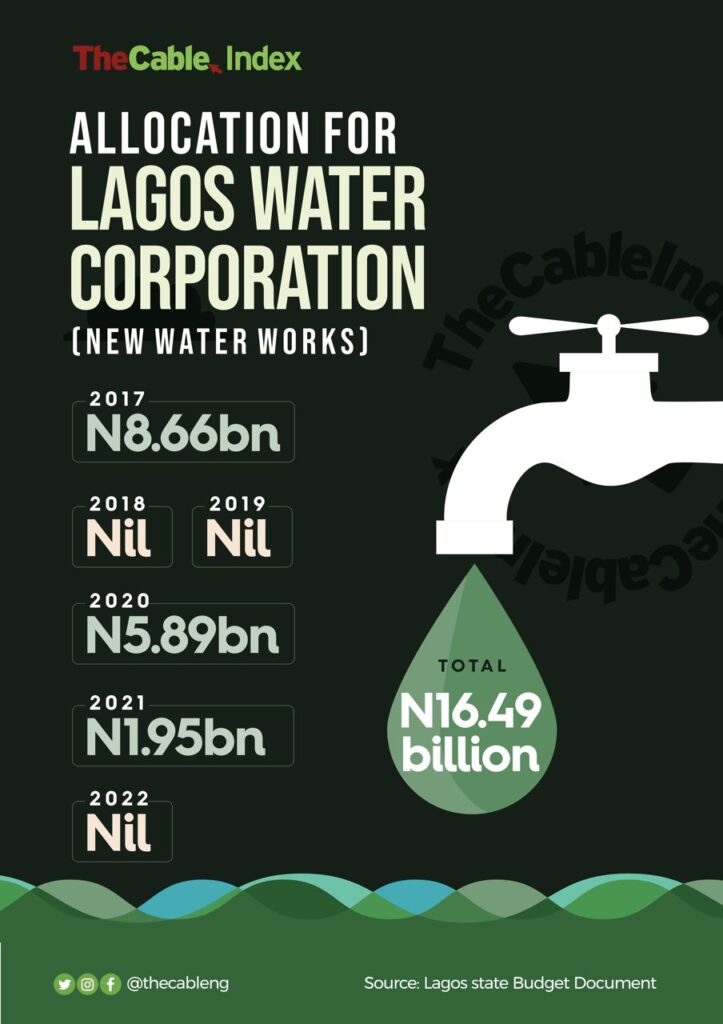

Also, further checks on the state’s budget to the organisation in the six years under review showed a total of N16,498 billion was earmarked for an item tagged, ‘LWC (new water works)’, implying that the state had planned on building new waterworks.

TheCable Index also observed that Lagos only made this allocation in three years out of the six years reviewed: 2017 (N8,656 billion), 2020 (N5,891 billion), and 2021 (N1,950 billion).

But in spite of the allocations, Badmus insisted that projects were underfunded. By implication, allocations were made, but only a paltry of the fund was released.

“It is true that we said we were working on the mini and macro water works at that time. At that time, we had about 48 mini and macro waterworks that we are supposed to rehabilitate. The estimate at the time was supposed to be about N5 billion or thereabout for the mini and micro waterworks alone, not the large waterworks,” Badmus said.

“We received less than N800 million. I think you understand. So, how much would that do? But we were able to manage it with the little revenue that is coming in to really run it. Now we are back to the same thing and I believe the governor is also looking into how and when we’re going to rehabilitate those structures after he finishes with the large waterworks. The large waterworks supply the major parts of our water here.

“The government is doing its best based on the availability of funds which has to be shared among different agencies. So, the little that we get, we are spending it on rehabilitation. It may not be enough because these things are not coming cheaper.”

Badmus said the 70mgd Adiyan water treatment plant phase II project, which started in 2013 has also suffered delays like others. The water plant was supposed to be an 18-month project, but poor funding has stifled its timely delivery. However, he said the plant, now at 83 percent, would be completed in about 14 months.

“The problem with that, again, is because of intermittent non-availability of funding. The contractor will stop and go and each time they stop, it takes a while before we can get them back to work again. The government is aware of this and that is why they are also working on funding it. We only have about a year to finish that project.”

Water is a fundamental part of all aspects of life. It is inextricably linked to the three pillars of sustainable development, and it integrates social, cultural, economic and political values.

Mayokun Iyaomolere, an environmentalist at Aqua Planet Nigeria Limited, said the water crisis in Lagos could impede efforts toward achieving the sustainable development goals (SGDs) by 2030 or even erode the gains made so far.

Iyaomolere said one of the SDGs that deals with water is goal six — clean water and sanitation.

“There’s no way water does not affect many of the goals even good health and well-being which is goal three because if we don’t have quality water, if you don’t have water in good-enough quantity it could also affect your health,” Iyaomolere said.

“So, if many people or most people in the states still do not have access to public water facilities at this time or if they do not have access to it by 2030 then that goal is not achieved. So, we are not doing well yet in Lagos and Nigeria in this regard because most people have to hustle for their own water to drink.”

As things stand, most Lagos residents will continue to depend on unsafe water sources until the state is ready to fund and complete ongoing projects.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment