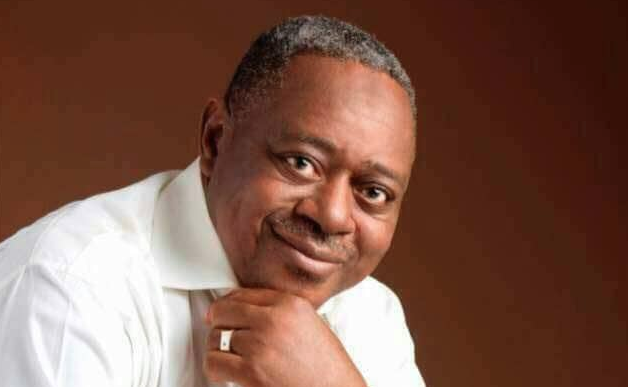

MINISTER OF AVIATION SEN SIRIKA BRIEFS PRESS ON MORE INTERNATIONAL FLIGHT BAN. 1&1A. The Minister of Aviation Senator Hadi Sirika briefs State House Media on the needs to ban international flight from two more Countries making it a total of 15 Countries from coming into Nigeria as a result of Coronavirus pandemic durig a chat at the State House Abuja. PHOTO; SUNDAY AGHAEZE. MARCH 20TH 2020

BY OYIN’ KOMOLAFE

On March 18, 2020, the Nigerian government finally heeded the calls of several concerned Nigerians and placed a ban on travels from thirteen “high risk” countries which had recorded more than 1000 cases of the coronavirus pandemic. Those countries include, inter alia: China, Italy, Iran, Germany, and the United Kingdom. But, Nigeria was not the first country to adopt such a measure in order to contain the coronavirus pandemic.

Kenya recently adopted an even more stringent measure by banning all travels from any country with confirmed coronavirus cases. However, Nigeria’s travel ban has raised several legal questions, ranging from whether Nigeria is under an obligation to evacuate its citizens from high-risk countries to whether Nigeria can legally turn down travels from its own citizens, even if such travels are from high-risk countries.

SCOPE OF THE FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT

Generally, freedom of movement, as enshrined in section 41(1) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999(as amended), constitutes three arms:

- The right to move freely around Nigeria and to reside in any part thereof.

- The right to leave Nigeria.

- The right to be granted entry into Nigeria.

However, the focus of this discourse is the right to entry. The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999(as amended), states: “… No citizen of Nigeria shall be expelled from Nigeria or refused entry thereby or denied exit therefrom”.

Advertisement

The use of the expression “citizen of Nigeria”, connotes that the freedom of movement is seemingly restricted to citizens of Nigeria. No doubt, non-citizens may enjoy some measure of freedom of movement, it is, however, subject to the provisions of Nigerian laws.

In the same vein, chapter 12(1) of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (Enforcement and Ratification) Act, states that: “Every individual has the right to leave any country including his own and to return to his country”. This provision is especially cardinal to the Nigerian legal system by virtue of the fact that the Act has gained the force of Law in Nigeria, pursuant to Section 1 of the Act.

CAN NIGERIA LEGALLY TURN DOWN ITS OWN CITIZENS TRAVELLING FROM HIGH-RISK COUNTRIES?

There is no gainsaying the fact that Nigerian citizens who do not hastily make their way to Nigeria before the travel ban may be officially imposed, may find themselves stuck in foreign high-risk countries. This may raise questions on the violation of the freedom of movement, and Nigeria’s obligation to adequately protect its citizens. No doubt, Nigeria has an obligation to protect its citizens, and most importantly, ensure the protection of their fundamental human rights as enshrined in Chapter IV of the Constitution.

Advertisement

However, the right to entry, like every other human right, is not an absolute right. Section 41(2) of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), indicates instances where a citizen may be deprived of the freedom of movement. The provision provides that a law may be reasonably justifiable in a democratic society, where it imposes a restriction on the movement of any person:

- Who has committed or is reasonably suspected to have committed a criminal offence, in order to prevent him from leaving Nigeria.

- In order to provide the removal of such a person from Nigeria, for trial outside Nigeria or to serve a term of imprisonment outside Nigeria, provided that there is a reciprocal agreement between Nigeria and such other country with respect to such a matter.

The exceptions provided by this section do not, however, cover instances of derogation which may be justified by reasons of public health or safety.

As stated by the court in the case of Okafor v Lagos State Governor & Anor(2016) LPELR-41066(CA), the provision of Section 41(2) “is not a carte blanche for a law that is reasonably justifiable in a democratic society. It is qualified by what such law that impinges on the right to freedom of movement should dwell on”(emphasis is mine). What this means is that Section 41(2) does not provide an expansive exception for the derogation of the freedom of movement.

It merely restricts the justifiability of any law which may be relied on to deprive a citizen of the freedom of movement, to the two exceptions given in subsections a and b, as well as the proviso thereunder. The implication of this interpretation is that any such conditions which do not fall within the ambits of the exceptions provided by Section 41(2), would not be admitted as being a legally recognisable exception to the freedom of movement.

Advertisement

However, section 45 of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), provides a leeway. The provision states that nothing in Section 41 shall invalidate any law that is reasonably justifiable in a democratic society; in the interest of defence, public safety, public health and public order or for the purpose of protecting the rights and freedoms of other persons.

The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights(Enforcement and Ratification) Act, reaffirms this provision, as Chapter 12(2) of the Act states that the right(freedom of movement) may only be subject to restrictions provided for by law, for the protection of national security, law and order, public health or morality.

The implication of these provisions is that should the Nigerian government decide to, it can legally deprive a citizen of the freedom of movement, and by extension, the right to enter into Nigeria, as long as such reasons which may be given for such actions, fall within the ambits of the provisions of section 41(2) and section 45(1)(2) of the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (amended).

IS NIGERIA UNDER AN OBLIGATION TO EVACUATE ITS CITIZENS FROM HIGH-RISK COUNTRIES?

It is pertinent to note that the rights enshrined in Chapter IV of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), are negative rights. What this means is that such rights only oblige inaction and non-interference, and this is where it stops.

Advertisement

They do not compel the government to adopt special measures to either evacuate its citizens from countries with high risk of coronavirus, or to assist persons who might be stuck in other countries due to the coronavirus pandemic. This played out with the recent agitations of the Nigerian students who were stuck in Wuhan and implored the Nigerian government to order their evacuation.

Although Section 14(2)(b) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), provides that the security and welfare of the people shall be the primary purpose of the government, the provision is, however, non-justiciable. That is, it cannot be enforced in a court of law. This is because Section 6(6)(c) of the 1999 Constitution(as amended), ousts the jurisdiction of the courts to entertain any case which borders on any issue related to Chapter II of the Constitution, under which Section 14 appears.

Advertisement

However, as much as the provision of Chapter 14(2)(b) stands as being non-justiciable, it is not a dormant provision and as such, it should guide the actions of the government. In essence, this author argues that the Nigerian government is indeed, under an obligation to protect the welfare of its citizens by evacuating them from high-risk countries.

However, it is submitted that it goes against the primary purpose of the government to leave Nigerian citizens stuck in high-risk countries without providing measures for them to be evacuated, as this could potentially affect the welfare of such citizens for which the government is under an obligation to protect.

Advertisement

CAN NIGERIA REFUSE TO ADMIT DEPORTED NATIONALS FROM HIGH-RISK COUNTRIES?

A rather interesting issue as regards Nigeria’s travel ban, also borders on whether Nigeria can, by reason of the need to ensure public health, legally refuse to admit nationals who may have been deported from high-risk countries.

Currently, there is no international convention, to the knowledge of the author, that expressly compels state parties to “admit” nationals who may have been deported by other countries. At most, sanctions for such refusal may be imposed on such a country by the host countries.

Advertisement

For example, the United States battled with deportation issues for many years due to the refusal of a number of countries to accept the nationals who had been issued deportation orders by the United States government. These persistent refusals led to the imposition of visa restrictions on four countries–Cambodia, Eritrea, Guinea and Sierra Leone– by the Trump government in 2017 for the sole reason that these countries had either denied or delayed admission of their deported nationals.

For some countries, there are express domestic provisions for such situations. Section 44(1)(g) of the Immigration Act of Trinidad and Tobago, provides that the Minister might make regulations on prohibiting or limiting admission of persons who are citizens of a country which refuses to re-admit any of its nationals who are ordered deported. In the celebrated American case of United States ex rel. Hudak v. UHL & Ors, where the court conceded that sovereign countries possessed the power to deport an alien to his/her country of origin, but further stated that the power was limited only by the power of the “native sovereignty” (that is, the country of origin of the deported person) to refuse to receive the deported person, if it so chooses. The court also stated that the power of the native country to refuse the admission of its deported national, is absolute– in the absence of a treaty which provides otherwise.

Flowing from this, Nigeria may refuse to admit its deported citizens on the ground of public health, especially by virtue of the leeway provided by section 45(1)(a) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended). This would, however, not render such persons as stateless persons because statelessness connotes the lack of nationality.

The mere refusal to accept a deported Nigerian citizen due to the coronavirus pandemic, does not strip such a deportee of his/her citizenship. It only puts a temporary hold on the right of entry of such a citizen.

In conclusion, the Nigerian government can legally prevent its own citizens from entering into Nigeria where such citizens are found to be travelling from high-risk countries. In the same vein, the law neither compels the Nigerian government to evacuate its citizens from high-risk countries, nor to admit deported citizens in the face of a global pandemic.

However, it is submitted that it goes against the primary purpose of the government to leave Nigerian citizens stuck in high-risk countries without providing measures for them to be evacuated, as this could potentially affect the welfare of such citizens for which the government is under an obligation to protect.

Oyin’ Komolafe is the prosecutor of the faculty of law, University of Ibadan and editor at the Ibadan Review. She can be reached via [email protected].