The Babcock Model United Nations invited the immediate past president of the United Nations General Assembly, Tijjani Mohammed Bande, to a live virtual session on August 5th this year. In the event tagged “reaffirming collective commitment to multilateralism”, one of the participants asked the diplomat an important question: “Is the United Nations aware of the genocide and ethnic cleansing going on in Southern Kaduna, and if it is, why is it not speaking up?”

“It would be a stain on the conscience of the UN to allow a Rohingya type situation in Nigeria,” the commenter added.

When Mr Bande finally attended to the question, he responded with consternation, making problems with the choice of labels used, namely “big words” such as “genocide” and “ethnic cleansing”.

After dancing around the issue, he offered a vague answer that hardly touched the issue raised, and, while ending with a terse rebuke of his transducer, he added that he has a personal stake in the matter.

Advertisement

Mr Bande played his diplomatic game quite well, saying so much while saying so little and ending up not saying anything at all, and that is the problem. The United Nations, which was set up in 1945, turns 75 this week, and as tradition has necessitated over the years, the annual general assembly is currently taking place. It is virtual this year, however, because of the novel coronavirus pandemic.

When the founding members of the UN created it as a replacement for the League of Nations which failed to prevent the Second World War, the idea and focus was a global body to prevent future outbreaks of war through diplomacy. That the UN has existed 75 years is a remarkable feat. The League of Nations died an ignoble death just after 20 years of existence on account of its inability to prevent the outbreak of another global war. How the UN has fared since 1945 has been the subject of a lot of debate, but while its major purpose of preventing the outbreak of a third global conflict (through the efforts of the Security Council), its record of preventing civil wars and genocide is a question mark on its record.

The Spanish Civil War that began (1936-1939) 1939 is a stark reminder for the international and geopolitical schemings that permeated the Rwandan Genocide of 1994. In both instances, the global body was caught flat footed as thousands of people were murdered. But what is even more fitting in this example is the Armenian Genocide that lasted nine years between 1914 and 1923. In both the Spanish and Armenian cases, politics between the major powers (Britain, France, and sometimes the Soviet Union) about their diverse interests took centre stage as both countries burned.

Advertisement

The international powerplay and game of interests between Belgium, France and the East African countries and leaders reared its head again in 1994 in Rwanda as 800 000 people were killed between April and June. Five years later, United Nations Security Council resolution 1244, adopted on 10 June 1999, after recalling resolutions 1160, 1199, 1203 and 1239, authorised an international civil and military presence in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and established the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo. This came right after its dilly-dallying has allowed ethnic Serbs Slobodan Milosevic and Ratko Mladic to run riot and kill thousands during the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Kosovo.

One can concede to Stewart Patrick (James Binger senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations) that multilateral bodies do not spring magically to life in crises, nor are they immune from geopolitics. The problem is that the UN has allowed geopolitics and too many competing interests to tie its hands from nipping a problem in a bud before it threatens international security. The Syrian civil war was a textbook example of how the UN has refused to learn from its well documented 20th century gaffes, thus surrendering the Security Council chambers to a place of competing narratives occasioned by the many accounts of the use of chemical weapons in Homs (2012), Aleppo and Damascus (2013) and Idlib (2017), in direct violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention. Even with the concession that the UN cannot intervene without the permission of sovereign states, its record in speaking out before the situation gets out of hand is dismal.

An honest appraisal would concede that multilateral institutions reflect the preferences of their major members. This has largely been the case with the story of Uighur Muslims under persecution from the Chinese government in its Xinjiang province. That the existence of such “reeducation camps” exist without being raised as an issue of gross human rights violations, by the General Assembly or the Security Council, is a pointer to the fact that the United Nations is being sabotaged from within and by itself. The rise of China and its frequent use of its veto in the Security Council (to likely shoot down any mention of the Uighurs) is a prime example of how problematic the system has become, leading to important calls for institutional reforms. But even before that is done, the Muslim world’s tacit silence and aloofness over the plight of the Uighurs, in comparison with its response to Myanmar during the Rohingya refugee crisis of 2017 is symptomatic of how its priorities take a shift especially when it is faced with cheap loans and infrastructure. In the Rohingya case, asides the Muslim world making its case, the response of the generality of the United Nations and its leading members was slow enough to let Myanmar’s military displace the Rohinhgya from Rakhine. When the secretary general Antonio Guterres finally decided to (or was allowed to act), it was not so much as calling the actions of the Burmese “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing” as much as it paying lip service and letting Bangladesh choke under the weight of caring for refugees without help.

Just like the Rohingya, the situation in Southern Kaduna in North West Nigeria is following the same established patterns: killings and displacement of ethnic minorities by a much stronger or sometimes state sponsored group; denial of such asymmetric and semi low intensity conflict by the national government; and like the Yugoslavia situation, silence from the United Nations until shit hits the roof.

Advertisement

The international community’s willingness to take the submissions of the Nigerian federal government which has labelled the conflict a “clash” between herdsmen and farmers is a direct is a case of living in wanton lethargy, which in turn is providing a space for the conflict to spread to previously unaffected areas of the region.

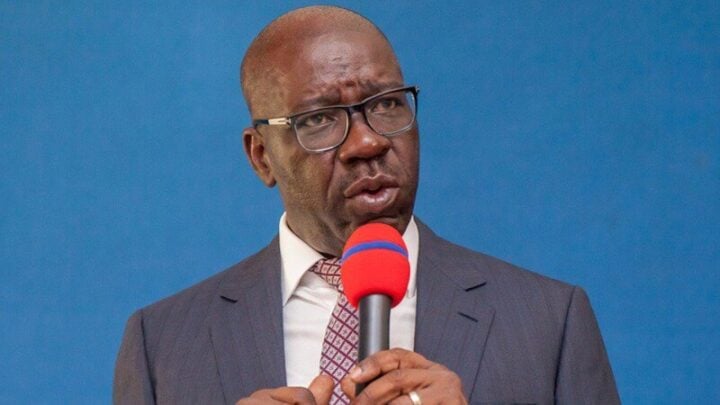

There is no place this lethargy is more epitomised than in Mr Bande’s response. When he said he has personal stakes in the matter, it is important to contextualize his cryptic message. Amb. Bande is an ethnic Fulani from Kebbi state in the same North West dominated by Fulanis. Most of the killings in the larger region–which, to concede, have been taken over by criminal elements exploiting the poor security network–have been attributed to the Fulani. He was appointed Nigeria’s permanent representative to the United Nations by President Muhammadu Buhari, another ethnic Fulani, but from Katsina state in the same North West region. Being a Muslim like almost every other Fulani out there puts Bande in a precarious position to 1) call out his kinsmen on their actions on a Christian minority; 2) speak out and incur the wrath of his principal the president.

It is this dilemma–the dilemma of silence and personal interests–that has come to define the response of the United Nations in issues it does not consider worthy of kickstarting a third world war, compared with the international and UN response to the assassination of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani by the United States in January this year.

In every internal conflict listed above, one thing is clear: the failure to condemn, and not just condemn, but also act, has robbed the UN of its ability to prevent internal issues becoming an international nightmare. If the migration crisis that began in 2015 taught, and is teaching us any lesson, it is that the United Nations’ reactionary nature and organizational inertia are fuelling more crises than it has had any will to solve, and that any institutional reform would largely fall flat if it does not change its approach to budding conflicts that have, and may turn out to be threats to the international system.

Advertisement

Macharry is a security analyst at SBM Intelligence

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment