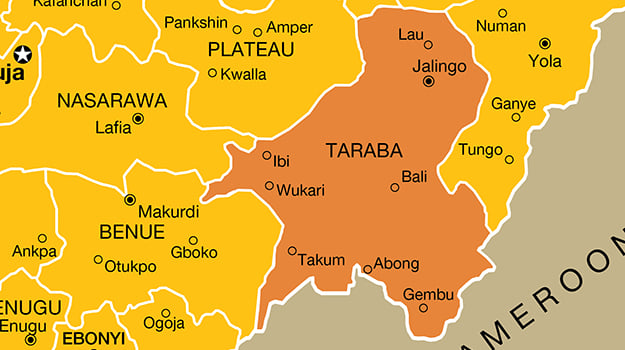

A typical rickety vehicle using to transport petrol product in jerrycans into Konni town in Niger Republic

The inscription on his shirt was glaringly ironic: ‘Say no to crime’. But Officer Monday and the caption were worlds apart. “Fuel business is easy,” the police officer told TheCable during visits to Seme and Owode-Apa, two of Nigeria’s border towns with the Benin Republic, where fuel smuggling thrives and sustains the local economy.

“I did it for more than a year before I decided to concentrate more on transporting people (smugglers),” Officer Monday continued as he provided insight into the fuel smuggling business costing Nigeria billions of naira annually.

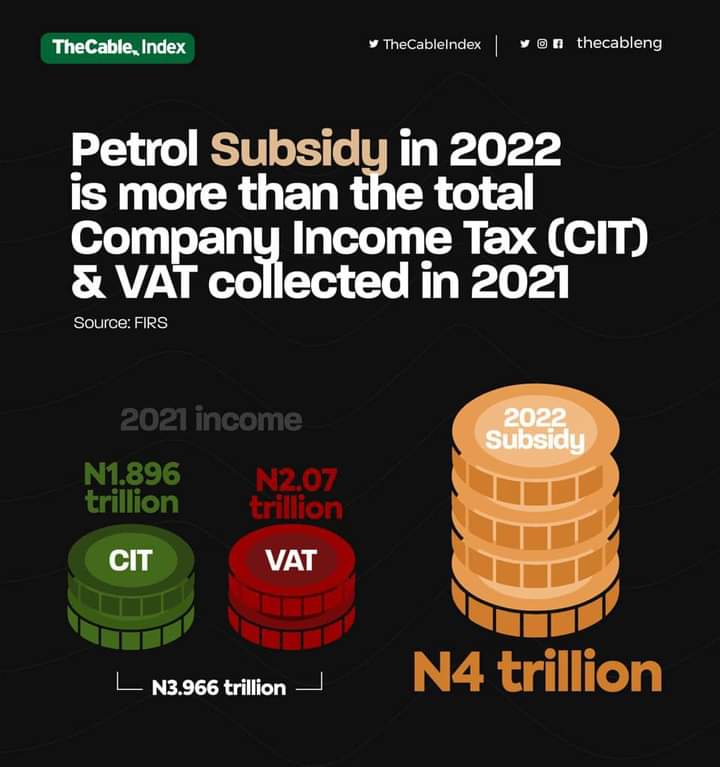

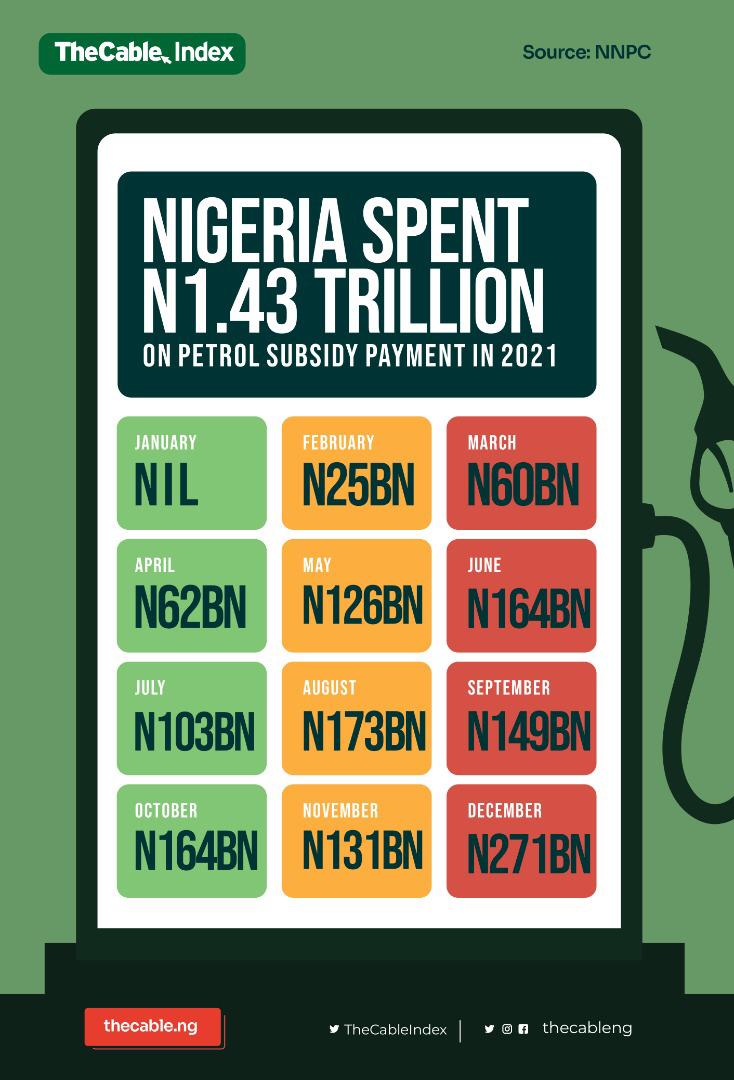

Daily, at least 42 million litres of petrol are smuggled out of Nigeria at a resultant cost of about N2 billion, according to the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). With millions of Nigerians grappling with periodic fuel shortages and amid the clamour for the removal of fuel subsidy which is said to gulp N150 billion monthly, investigations by TheCable reveal a black market of subsidies; one in which individuals smuggle thousands of gallons of fuel to Nigeria’s neighbours in well-coordinated operations with support from security operatives.

Advertisement

From Benin Republic to Niger and Cameroon, TheCable documented how security operatives like Officer Monday pave the way for the lucrative fuel smuggling business or, in the least, turn a blind eye for the crime to continue unabated.

In Ikom, Cross River state, where Nigeria’s border with Cameroon lies, the business of smuggling fuel into the neighbouring country is controlled by an “elected government” made up of a chairman and other members of an executive council. Their key responsibility, according to some members, residents, and as TheCable observed, is to coordinate the illegal business and pay “settlement” fees running into millions of naira to security operatives to look the other way.

“If I buy fuel of N5,000 (per gallon) from Nigeria, which I usually load inside a sack, I’ll make something close to that amount as profit after selling it in Benin Republic,” said Officer Monday, who said he is attached to the Badagry division of the Nigerian police.

Advertisement

THE BENIN REPUBLIC ROUTE

The Seme/Owode-Apa axis of Lagos state is smugglers’ choice route for illicit trade despite the heavily-armed security personnel and checkpoints that dot the road.

“With your car, no one will disturb you and even if they do, N500 is all you need to pay,” said Monday King, a smuggler based in Seme. “Just fill your tank and cross to Benin where you will sell it.”

Smugglers moving fuel through this and other routes are on the safe side only if they know a security officer, according to a police personnel identified as Sir K, who, like Monday, is also involved in fuel smuggling and transporting smugglers. “You have to know the police, customs, army and others if you want to do the business successfully on this route (Badagry/Seme/Owode-Apa),” he said, his hand spreading out towards the dusty path.

Advertisement

His account turned out to be true when TheCable’s reporter transported fuel in a 10-litre gallon along the route in the company of one Paul, an ex-soldier who’s an acquaintance of Officer Monday.

And despite carrying the fuel and not having a passport, there was no confrontation from any of the personnel in the nearly 20 security checkpoints counted from Badagry to the Owode-Apa border.

“Here, anything goes,” said Paul who is known in the area as Bishop. “You can transport guns to Ghana, Togo if you work with the right person,” he continued, before adding that “they didn’t disturb us because you’re with me”.

At Kpoguidi, which is about 50 kilometres from Badagry, the 10-litre gallon of fuel was sold at N220 per litre – more than the N165 it was bought, leaving a profit of N55 for each litre. But there is even a bigger deal for the Beninese: a litre of petrol in the country is sold for XOF 520 ($0.899 and N368.45), according to data from the tracking platform, Globalpetrolprices.com, which means that for each litre bought in Nigeria, there is a gain of at least N200 to be made if the smuggler sells directly to the Beninese market.

Advertisement

In Owode, a border town in Ogun state, TheCable found that all one needs to move petrol with ease to Benin Republic is to pay N67,000 for a ‘pass’ issued by unidentified officials of Nigeria Customs Service (NCS), according to smugglers who ply the route.

It is a “very lucrative” business and often done at night, said one Akeem who works as both a smuggler and a motorcyclist.

Advertisement

Plying one of the many routes through which fuel is smuggled into Benin Republic, TheCable reporter paid N800 at four checkpoints manned by Nigerian security officials — including the immigration, police, soldiers, and customs.

“The customs officials on the road, they’re not there to catch (arrest) smugglers,” said Saheed, who said he has been smuggling fuel along the route since 2017. “As you’re looking for money, they are also doing the same.”

Advertisement

Atiku Samuel, a public policy analyst, told TheCable that the trend of fuel smuggling shows that agencies such as the customs “have failed” because “they fixate on how much revenue is being generated, while their core mandate — which is to protect our borders — have been jettisoned”.

Advertisement

THE BUSINESS OF ILLEGALITY

Fuel smuggling has become the mainstay of several inhabitants of border communities and security operatives, some of who are directly involved, while it has created indirect employment for many others.

“If you have the money and understand the business very well, you’ll make up to N200,000 to N400,000 per week,” said Iya Ibo, also known as Psalm 91.

Iya Ibo is among those who have made fortunes from the illicit business. She has reportedly bought two cars with proceeds from fuel smuggling.

In various border communities, an obvious trend was how residents, particularly youths, appeared to have found succour in the business.

In Benin Republic, TheCable found that buying and reselling fuel from Nigeria is a major occupation for residents in various towns including Seme Krate, Kpoguidi, Hovidokpo, and Igolo where trucks and other private vehicles from Cotonou were stationed at various points to buy smuggled fuel from Nigeria.

Apart from directly running the business as a manager and transporting fuel along the various routes, there is almost an opportunity for everyone interested: There are those who sell the gallons and sacks used; some who load the fuel while others provide cover and act as informants for the smugglers.

There are even artisans who construct additional tanks for vehicles used for smuggling petrol, often at the cost of between N40,000 to N80,000 for a tank that could take 300 litres of petrol.

But while the direct and indirect players are thriving as a result of the illicit trade, Nigeria’s petroleum sector continues to bleed, with a system that appears to be rewarding the most fraudulent despite the government subsidy in place.

CROSS RIVER-CAMEROON: THE NITRATE UNION

In Ikom LGA in Cross River state, Nigeria’s border with Cameroon, it is a widely-held belief that some fuel smugglers are “far richer” than most senior government officials.

“Nitrate chairman is richer than the local government chairman because of the money they make,” said former fuel smuggler Joshua Obaji, in reference to the Nitrate Union, a body of fuel smugglers in Cross River state which demands about N1 million as registration fee from screened and “well-connected” members.

“If you are the chairman of the Nitrate Union and business is moving very well, in a week, you are entitled to N20 million,” added Obaji, who is currently out of business.

Smugglers moving fuel from Cross River to Cameroon operate under the organised cartel known as Nitrate Union, a branch of the United Border Across, the umbrella union that oversees the smuggling of all kinds of commodities across the Cameroon border.

“They supervise the carrying of fuel from here to Cameroon, they also have a body in Cameroon. The head of the union is rotated between Ekpache Ekome in Ikom, Ajaso in Etung and Ekok in Cameroon,” said Obaji whose house is just a stone’s throw from Ikom River from where the fuel is transported to Cameroon.

Here, smuggling to Cameroon is through road by night and river by day, mostly with the support of security agencies — according to smugglers, union leaders, residents and local authorities.

“Some J5 (cars used to transport the fuel) carry as many as 250 twenty-five litres (gallons) and we pumped 2,000 gallons the last time,” said one member of the male-dominated union who refused to disclose his name.

At N180 per litre, the gain for each gallon – bought during his last sale at N4,500 and sold for N7,500 – is around N3,000. With 2,000 gallons, that would yield N6 million, leaving a profit of around N3.5 million for each sale when transportation and settlement fees of about N2.5 million put together are subtracted.

It is a simple but secretive process, explained a business manager of a Nitrate Union member who simply identified himself as Odey. “If you have 1,000 rubber (jerrycans), we have what is called declaration; you will declare with the chairman – one rubber is N800, so you will calculate N800 by 1,000,” he said.

“That money na for Ghana Must Go, you go drop am for petrol chairman table, he go now give you pass to pump. When you pay, chairman is in charge to go and see customs, see immigration; all the forces; they have an amount they will collect and share within themselves.”

“Seizing (of gallons of fuel when smugglers are caught) is only when you don’t settle them (the security personnel) or when they do not permit you to go and pump and you are pumping. It is only after the security agencies give go-ahead to the chairman that he can declare with his people,” Odey continued.

“They already have an understanding and they have collected the money they are to collect, so people can then pump (fuel),” he said, noting that the operation is carried out between four to seven times a month and that smugglers still settle security personnel while transporting the petrol from the filling stations to Ikom River — and onto the warm embrace of large canoes.

Bribes paid to security agencies for such transportation can vary “from N2 million, N5 million or N1.5 million,” said a driver who helps the smugglers to transport their product. Popularly known as Safi, he said “we normally start our business (transporting fuel to the river from the filling stations) by 1am in the night. When it is 6am in the morning, we stop it. When you settle the police, you do your business and find your way out”.

Whenever pumping is “declared” for members of the union, they go in batches, mostly at night, and across the span of three days, with wealthier ones buying at least 1,500 to 2,000 twenty-five-litre gallons, according to Odey and several fuel attendants.

Filling stations turn out to be the engine of the smuggling business. Within Ikom town, smugglers identified at least five where fuel is being pumped steadily to be illegally transported to Cameroon.

“Before they come to do pumping at the filling station, we see their receipt used to declare,” said one fuel attendant at Bodagri Nigeria Limited, a station along Ikom-Ogoja road. “If you don’t have receipts, that means you didn’t declare and you want to be doing it secretly.”

The Nitrate Union system ensures there is compensation for members who run into any trouble while transporting fuel just as there are penalties for those who buy fuel outside of approved days or above the “declared” quantity.

“We have task force both for water and land… if you pump more than … (or) if you don’t show your pass, they will seize it,” Odey added.

From local government areas like Ikom and Obubra, smugglers buy fuel in 25-litre gallons and transport them to Ajaso and Mfom communities from where they are loaded into canoes heading to Ekok, a bustling Cameroonian town situated less than five kilometres from the border.

Once the gallons of petrol are offloaded from the canoes in Ekok, they are taken to the point of sale referred to as Petrol Market.

Over the course of two days in the town, TheCable observed that the economy is largely driven by smuggling; from the youths carrying gallons to and fro the river to transporters, informants as well as traders selling gallons of petrol.

Apart from members of the smuggling cartel who deal in thousands of gallons, young boys often smuggle one or two gallons along the Ikom border.

Underneath tree shades, inside uncompleted structures, and around the bushes along the border, TheCable found gallons tucked away, some of which were filled with petrol.

To escape security operatives and the union task force within Ikom, the young smugglers go to Obubra LGA, about 90 kilometres away, where they are able to pump as many gallons as they want, but face a higher risk transporting them to the river.

For such persons who don’t belong to the union, the penalty is stiffer, said Odey. “If they seize your fuel, they auction it…customs can auction each gallon N3,000 and people will be rushing. Some of the officers buy and resell.”

Tengi George-Ikoli, a petroleum public policy expert, said to end fuel smuggling, Nigeria must strengthen process reforms to accurately track end-to-end transportation of fuel products within the country, ensure stronger border controls and adopt a whistleblower policy.

Tengi, who is the program coordinator at Nigeria Natural Resource Charter (NNRC), added that “implementation of the deregulation policy declared in 2020 and the legal framework incorporated in the Petroleum Industry Act 2021 to aid deregulation will go a long way towards eradicating the price distortions that make it attractive to smugglers”.

THE DUSTY, DANGEROUS ROUTE TO NIGER

For four days, TheCable monitored the smuggling of fuel and other contraband through Nigeria’s poorly-policed border with the Niger Republic.

As previously reported, the Niger border is grossly under-policed, such that large swathes of land exist with no single security operative on sight as the personnel in charge, including a joint security team known as border patrol, are overstretched.

Smugglers described how jerrycans are transported in large quantities with the aid of woven sacks. This helps in carrying “a large number of jerrycans on a trip” through the porous border, said 30-year-old Jamiu Ali.

Ali added that while weekends and nights are suitable for rickety vehicles with extra tanks, motorcycles and tricycles are used during the daytime, adding that “there is no presence of law enforcement” along notorious routes such as Gidan Kamin, Bakin Dutse, Geti, Babadede, and Gidan Ketsu.

At Illela, a border community in the northern part of Sokoto state, Kabiru Dan-Ilela is so popular that he needs no introduction to any of the travellers and drivers plying the route between Nigeria and Niger.

“I started this business long ago when I decided not to continue with my studies,” said Dan-Ilela, 25, before adding that he earns good money moving contraband across Nigeria’s border with Konni in Niger.

“I dropped out (of school) and joined others selling fuel in gallons at the roadside before I started using a car,” he added.

Shuaibu Mohammed, a resident in Sokoto, said he has been witnessing the smuggling of fuel into Niger for years. “Most of these boys learn the illicit trade at a tender age,” said Mohammed. “They see the idea of going to school at the elementary level as a waste of time.”

To assist the TheCable reporter in transporting petrol along the Illela route, Dan-Ilela broke down the process: “We package our products in woven sacks if they are transported by motorcycle. If you want to sell to me, I will buy twenty litres of jerrycan at N5,200 but if you have someone in Konni, I will tell my boys to collect N600 each for transporting a jerry can of fuel to Konni.”

The “boys” he spoke of, TheCable would later learn, are among dozens of 20-year-olds who run all sorts of errands for smugglers.

Dan-Ilela’s house serves as his depot, with not less than 150 jerrycans filled with petroleum products packed in woven sacks and ready for transportation.

Apart from the smugglers who transport fuel in their cars, motorcyclists are also key beneficiaries of the illegal trade. Posing as a stranded truck driver, the reporter got one Dahiru Sani, a motorcyclist, to transport three jerrycans of fuel from Illela in Sokoto to Konni.

It is a brisk business in which the motorcyclists charge as much as N600 to transport a 20-litre jerrycan.

“On a motorcycle trip, we can load between 17 and 20 jerry cans with fuel depending on the rider,” Sani said.

“Any vehicle like 504 or Toyota Carina can load between 80 to 90 jerrycans depending on the vehicle and its extra tank. Even a bicycle can load three jerrycans.”

According to residents, security operatives are endangered species along the route, with some sharing stories of how they are often overpowered by smugglers, leading them to stay away.

While travelling with Sani to Konni, TheCable came across two vehicles belonging to the Nigerian customs which had been set ablaze. Some residents said the customs officials had stopped a vehicle carrying some contraband, infuriating youths and motorcyclists plying the road.

“It is a regular occurrence,” said a co-traveller. “The smugglers always have the upper hand against any law enforcement agencies that come their way because villagers will always support them.”

‘WE ARE HELPLESS‘

In November 2021, the Sokoto government signed an executive order prohibiting the sale of petroleum products in jerrycans in a bid to tackle the menace of insecurity.

But despite the fact that the order is still in place, TheCable found that it is being breached on a daily basis, particularly in border communities.

Ibrahim Magaji Gusau, chairman, Sokoto State Petroleum Monitoring Committee, said the smuggling of fuel across the Illela border is not unknown to the state government and security agencies.

“We are aware that petroleum products are being smuggled at the border but we are helpless. Our committee always ensures that there is no hoarding of fuel and ensures its dispels at official price to the public,” he said.

“But, the Illela scenario is not part of our mandate. The security agencies are in the best position to answer such enquiry.”

Ibrahim said while other local government areas adhered to the directive against the sale of petrol in jerrycans, border communities refused to comply.

“Some politicians who are owners of the affected filling station lobbied the APC federal lawmaker representing the area who secured the federal government permit for them to be excluded from the governor’s order,” Ibrahim alleged.

Abdullahi Balarabe Salame, the APC lawmaker representing Illela/Gwadabawa federal constituency, admitted that he assisted in reopening some petrol stations due to the “hardship faced” by the owners, but he queried the efforts of the security agencies who he says should be responsible for preventing the smuggling of petrol.

“I assisted some of the stations to be reopened due to the hardship faced by the farmers, motorists, etc, to alleviate their suffering,” he said.

“But no good citizen will give a helping hand to smugglers, talk less of myself who is representing both the government and the people in the area.”

When contacted by TheCable, Onyema Nwachukwu, army spokesman, said an investigation would be carried out to determine the involvement of its officials in the aiding of smuggling, adding that it is an “illegitimate and a punishable infraction”.

Joseph Attah, Nigeria customs spokesperson, said the agency “will not deal kindly with any operative found remotely connected with petroleum smuggling”, noting that the service has been “recording high volume seizures of petroleum products in recent times while strictly enforcing the 20km radius of the border for petroleum stations”.

On his part, Olumuyiwa Adejobi, police spokesperson, requested the names of officers involved in the “act of economic sabotage” to enable the force to investigate the matter.

“You will need to mention names or teams being caught in such act of economic sabotage, then we know how to channel our investigations. I am not so sure that any policeman will descend so low to have been involved in such,” he said.

“However, in case we have some of them who are deviants, kindly do us good by availing us more information about them, and their modus operandi.”

Reporting by James Ojo, Chinedu Asadu and Tunde Omolehin

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment