After altering his looks and taking psychiatric lessons every day for one week, investigative journalist ‘FISAYO SOYOMBO went undercover for three weeks in November, including 10 straight days on ward admission, as a patient of the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Yaba, Lagos, one of the nation’s most historic mental rehabilitation centres. His report unveils the decrepit state of hospital facilities, gross understaffing of critical staff despite a bloated workforce widely believed to be populated by ghost workers, low quality of service delivery, arbitrary charges on patients — all stemming from personal and institutional corruption and the hospital’s implicit stigmatizing of its very own patients.

...continued from Part I

‘THIS FOOD IS CLEARLY FOR MAD PEOPLE’

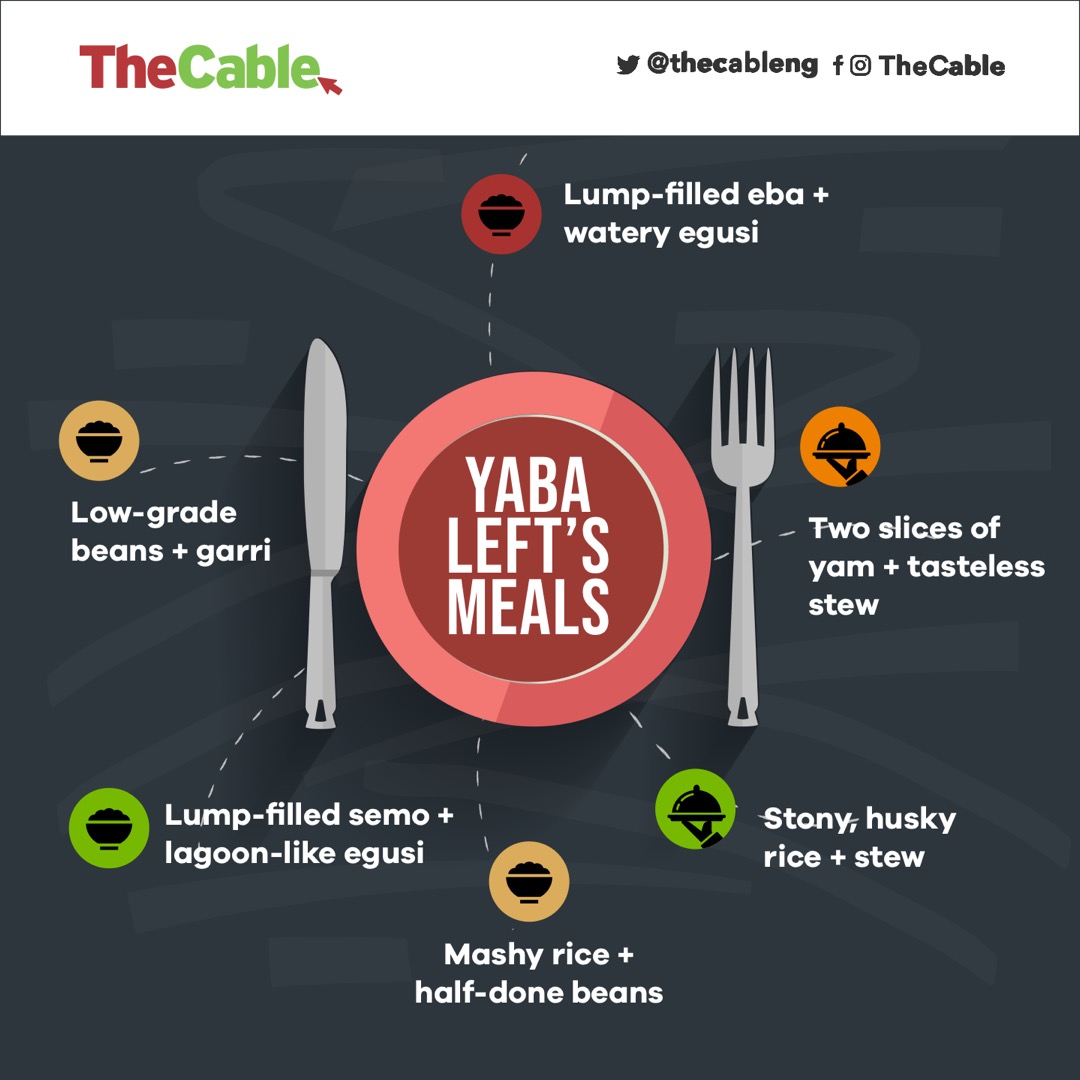

Thursday morning was pap and two pieces of bean cake. The general complaint was that the pap lacked the sugar that the servers claimed to have added. Afternoon was low-grade beans plus garri. Evening was lump-filled semolina and bland ewedu stew containing a pebble-size meat. Hard as I tried to eat, I couldn’t. That Thursday night, I lodged a verbal complaint with the male nurse on duty. “This is not fair,” I told him in an impassioned tone, personally pained because I was truly hungry. “It’s not like the hospital is rendering us a favour; we paid for this service.”

Advertisement

Friday morning was yam and stew; it ought to contain fish or meat but it didn’t. Afternoon was jollof rice, which, to be honest, was perhaps the only meal that tasted good of the 28 I ate at the hospital — a success rate of 3.6%. Dinner sucked away all the good of lunch; the eba was so lump-filled my appetite instantly went numb; the egusi was watery as usual and therefore tasteless. I threw it away and went to bed on empty stomach.

Saturday morning was pap and bean cakes; it was manageable. Afternoon was stony and husky white rice with stew. Dinner was irritating; the amala was so horrible I wondered if the lumps were deliberately introduced in it. I couldn’t believe that someone indeed cooked that and was proud enough to serve it to anyone.

“Look, the hospital management and the cooks in the kitchen prepare these meals like they’re meant for mad people,” one patient told me that night while I threw the food away for the umpteenth time. “Nobody in his right senses would serve this kind of food to a normal human being. No hospital will give this to regular patients. In their heads, we’ve run mad and our taste buds can’t spot ill-prepared food.”

Advertisement

A ONE-MAN PROTEST DEALT WITH ‘THE YABA LEFT WAY’

Breakfast on Sunday, November 24, was bread, tea and egg. Lunch was jollof made from low-grade rice. The eba served for dinner was well-done this time; however, the vegetable stew was so watery and stony it rendered the eba inedible. I managed to eat it without complaints but one patient who claimed to have studied Theology at a UK school couldn’t. It was the Sunday Sheffield United’s Olivier McBurnie scored a last-gasp 3-3 equaliser to deny Manchester United victory at Bramall Lane.

Marcus Rashford had just put United 3-2 ahead when the theologian abruptly switched off the television in the paved courtyard to the consternation of viewers. “This hospital is taking us for a ride and you all are here watching football,” he barked. “This food is sh*t. They do it all the time, and now it must stop.”

Advertisement

Many liked his anti-bad-food campaign but only a few supported his methods; they wanted to continue watching their TV, but he wouldn’t budge. A patient— let’s call him Yellow — stood up to him. There was uproar. Had they not been separated, Yellow and the theologian might have come to blows. During the melee, one patient kept warning the protester: “Looks like you don’t know where you are. This is Yaba Left o. The nurses will just change your drugs.”

“Changing of drugs,” as I was made to understand, is the practice of adding sleeping pills to the drug list of patients deemed troublesome by the hospital. I personally doubted the credulity of this claim, but by Monday the theologian was sleeping like a pregnant woman. He’d borrowed Dr. Olayinka Egbokare’s ‘Dazzling Mirage’ from me the previous day but hadn’t read beyond the opening pages. When I saw he’d spent more than half of Tuesday sleeping again, I approached him shortly before 5pm: “You’ve been sleeping all day like someone bitten by tsetse fly, man. What’s wrong with you?”

“Nothing, bro,” he replied. “I told the nurses the hospital food was making me purge, so they gave me new drugs.”

“Are you sure they didn’t ‘change your drugs’ because of your Sunday protest?”

Advertisement

“No, bro. Just drugs to stop the purging.”

I could tell he was living in denial. I almost believed him, in fact. But when I went looking for him half an hour later, he was back in bed, sleeping and snoring away, oblivious of my presence.”

Advertisement

This wasn’t the effervescent man I’d come to know for almost a week; he had become, as Darey would say, a “shadow of himself”.

FULL-BLOWN PROTEST

Advertisement

Monday morning was pap and bean cakes, afternoon was beans and yam, evening was another lump-filled yam flour with okra. I went into the nursing office not just to complain but to show the male nurse on duty. “You know that even if we were hopelessly mentally deranged, we don’t deserve this kind of food,” I told him. “You cannot continue doing this just because you think nobody is watching you.”

Advertisement

Truly, nobody was watching them. And if any drug patient dared report to his parents/guardian, they wouldn’t be believed for obvious reasons. Many of the drug patients, even those who weren’t psychotic, landed at Yaba Left in the first place because they had started to misbehave at home. The substances they were abusing had given them such false sense of confidence that they could insult anyone. The psychotic ones among them often hallucinated, felt persecuted, felt being gossiped about, saw ghosts, felt families and friends were ganging up against them and felt the entire world was against them. Therefore, if any of them complained about the hospital’s food, no one would believe. Such complaints would be viewed as one of the many manifestations of psychosis.

Breakfast on Tuesday was yam and stew, lunch mashy rice plus half-done beans, and dinner garri with stony egusi. Wednesday morning was sugarless pap with bean cakes, while lunch was mashy rice and egg with water melon. One patient who couldn’t take it anymore raised his voice against a nurse. “Please, hold your breath!” the woman exclaimed. “The people who served you the food were here minutes ago; you didn’t shout at them. Now that they’ve gone, you want to shout at me?”

The patients felt they’d directed their protest at the wrong quarters; they resolved to correct it. A protest was starting to brew. By the time the servers returned with dinner, the patients had seethed with rage for hours. Some of them had lined up with their plates but they were crowded out by the dissenting voices. Soon, they unanimously insisted they weren’t going to eat the food.

Stunned, the servers scampered to the nursing office for help. One elderly patient was impressed by the steam the nonviolent protest was gathering. I had picked out his face from the food queue the previous week when he politely asked a lady server if the yam flour to be served that day was not lump-filled. “Can you enter the kitchen?” the lady, clearly offended, had fired back.

“Don’t you have a father at home?” the man responded.

“Which father?” she snapped. “He’s in heaven!”

One nurse came to plead with the patients, promising that the food would improve, but her pleas were drowned by the angry voices of the patients. I couldn’t witness it to the end because my team had come to discharge me against medical advice, as laid out in the plan. I’d in fact been discharged an hour earlier but I managed to delay my exit by spending idle time in the toilet just to witness the protest.

“We will not eat this food… we cannot take this anymore,” I could still hear some patients shouting as I slipped through the gates of Tolani Asuni into the general space of Yaba Left.

I may not have witnessed the outcome of the protests but I really could tell, based on precedent. Five months back, in June, patients had staged a stiffer protest against the servers, insisting there wouldn’t be peace unless the CMD came forward to address them. A patient who was on admission at the time said the group went as far as insisting they would no longer take their drugs. “The CMD indeed came,” the patient said of the incident. “However, to the disappointment of everyone, when she tasted the food, she claimed nothing was wrong with it.”

‘PRINCIPALITIES AND POWERS IN THE KITCHEN’

The horrible food eaten by patients of the hospital is the end result of a complex mix of corruption and desperate office politicking. So said an employee of the hospital who asked not to be named for fear of retribution.

“There are certain people who have been in charge of the kitchen for a long time now; they are the ones who buy foodstuffs from the market,” said the source. “When the present CMD came in, part of what she did was to get those people out of the way. And it was quite messy — because there were accusations that their purchases were rarely commensurate with the released funds.”

The responsibility of buying foodstuffs and verifying the prices was then transferred to another committee. However, in terms of the cooking, the original set of people in charge of preparing the food remained in charge. Repeated complaints by patients prompted a decision to employ a dietician to oversee the kitchen.

“The dietician was frustrated out of the system by every means possible,” the source said. “And since her exit, nobody has been brought in for that purpose.”

The failure to replace the former dietician has meant a lack of professional input into the goings-on in the kitchen. For instance, when patients request special meals, the kitchen staff don’t seem to know what should be prepared. What the patients get, instead, is the same set of food served to all the patients.

“The complaints about the quality of food persist but the reasons are not clear,” the source concluded. “It is hard to say whether some of the foodstuffs are being kept back or not, but the final food output that we see is not palatable at all. And this has been going on for years.”

THE PATIENTS’ BATHROOM IS AN EYESORE

The first time I entered the toilet serving Tolani Asuni Ward, the scenery was so nauseating I wanted to puke. I ran straight back out! The tiles were either irredeemably stained or unrestrainedly peeling off the walls. Parts of the floor were somewhat waterlogged, helped by burst pipes that shelled out water in place of regular taps. The water closets had all lost their lids and, just like the pint-sized bathrooms, had become permanently discoloured by filth. Professor Asuni would be turning in his grave at the sight of the bathroom in the ward named after him!

One consequence of the shabby state of the Asuni toilet is the pressure it puts on Adeoye Lambo’s, still relatively new. A philanthropist — not the hospital management — renovated the Adeoye Lambo bathroom recently. This was a bathroom built for a small group, the 30 patients of Lambo, but it now serves no less than 20 more patients from Asuni. I was a late bloomer in this regard — until my sixth day at the ward, when, seeing that I was holding myself back from using the toilet, a patient asked me to “try Lambo like almost everyone else”.

‘CORRUPTION AND ALL THAT STUFF’

Someday during my first week of admission, there was almost an outbreak of fisticuffs between the theologian and another patient who is the son of a pastor, over the rights to the television remote in the lobby. Each wanted to see something on TV that the other didn’t want to. In truth, the pastor’s son was part of a small clique that controlled the TV remote; the theologian was indeed right to protest. As resentment welled up in both parties, the pastor’s son, clearly ego-battered at being knock off his perch, barked out to the theologian: “Look, I paid the same amount as you did to be in this ward, therefore I have the same rights as you do to watch whatever I want.”

Irritated by the raised voices, the nurse on duty intervened. “Please, you people should stop all this noise about how much you paid,” she cut in. “You think it is your money that was used to fund this DStv subscription? Look, most the of things you see around here are not from the management; you know this is Nigeria and there is corruption and all that stuff. Most of the social services you enjoy here were put in place by public-spirited individuals.”

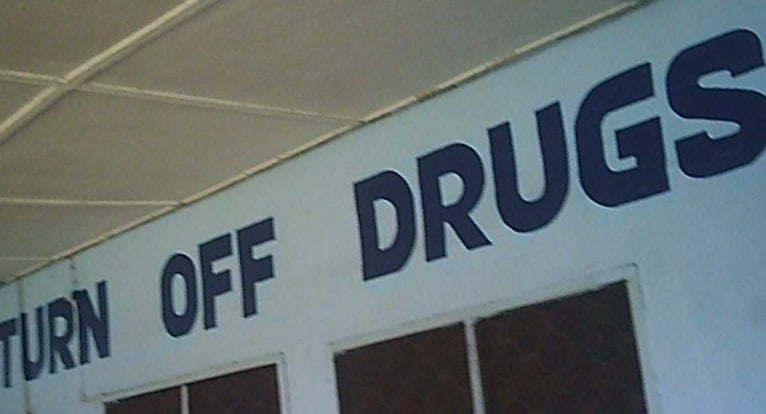

She hadn’t lied. I would later discover that the monthly DStv subscription was paid for by a doctor. The bathroom at Adeoye Lambo was renovated by an Egba chief. The hospital had sold him the idea of renovating Tolani Asuni as well, but he didn’t buy it, insisting he would only renovate Lambo because the late psychiatrist hailed from his town. The painting of the exterior of Tolani Asuni Ward, plus an inscription that reads ‘Turn off drugs, turn on the music’, was the idea of an arts-endowed ex-drug patient. Even the materials used for the painting were donated; they weren’t from the hospital.

‘WHO SHOULD MISBEHAVE IF NOT A MAD MAN?’

Not long after I got to the ward, I started to notice a thin, dark boy at Adeoye Lambo. He was restless and desperate to get out of the hospital. He must have been aged somewhere between 17 and 20; he had a few open sores as well. The first time I saw him, it was so early in the morning yet he was shedding tears profusely. Two problems. He wanted to leave the ward; and if he couldn’t, he wanted access to Mali Kush and Colorado, two of the many drugs he abused. In his first few days, he was pretty unstable, crying, howling, scratching his body, sometimes screaming incoherently and acting irrationally. For these, he often earned himself cheap slaps and whips from the nurses, much to the chagrin of one of the two elderly patients in the ward — a dark-skinned sexagenarian who always spotted a black pair of spotty boxer shorts. While he sometimes changed his vests, his black briefs were ever-present, leaving me wondering if he had so many pairs or he wore just one over and over again.

“You’ve started beating him again!” the man screamed one day. “Why?”

We were soon told he took some keys that weren’t his. I’m not sure if the keys belonged to a fellow patient or a nurse, but I remember the nurses were clearly displeased, and they beat him for it.

“He took keys belonging to a nurse and he wasn’t supposed to, and so?” the man queried no one in particular. “We say someone is mad, you say he is misbehaving? Who should misbehave if not a mad man?”

The elderly patient motioned the boy to come over, and to the surprise of everyone, he hearkened. The boy sat beside him, calm and attentive. I witnessed this two more times, that there was uproar and this man was the only one who could still the boy. How come the boy listened to him without a beating? The man blew his own trumpet on the third occasion.

“Without beating him, he listens to me when I talk to him,” he boasted. “No nurse should beat him. He may be mad but all he needs is love. He’ll do whatever you ask him to if you ask nicely.”

When asked to comment, a psychiatric doctor, who didn’t want to be named for fear of being seen as helping to plan the undercover work, condemned the act.

“It is a matter on two levels,” he says.

“I do not support beating a patient under any guise. But if a patient is violent — kicks at a doctor/nurse, bites someone and so on — maybe I can understand the beating, even though it still doesn’t make it right.

“However, if a patient exhibits stubbornness prompted by mental illness, such as the boy taking possession of keys that aren’t his, it’s not right to beat him. He wasn’t violent, why should he be rewarded with violence?”

Had the boy been beaten up at a hospital in the UK, the nurses in question would have been investigated and dismissed if found guilty. So said a Nigerian psychiatric nurse based in Camden, a district of northwest London, England.

“Even if a patient is violent, a nurse has no right to respond with physical assault,” she said.

“By policy here in the UK, if the patient hits you, you are not allowed to hit back. Mentally-ill patients are vulnerable people; they are vulnerable, that’s why they are in the hospital. If you hit back and there is a complaint, you will be investigated; if found guilty, you will be suspended or sacked, depending on the weight of your guilt. There are cameras everywhere so there’s always evidence.

“What that nurse can do is to restrain the patient. And it may interest you to know that the nurse cannot do it solitarily. You alone cannot; you have to involve a minimum of two staff. And then the extent of strength you invest into restraining the patient has to be commensurate with the scale of violence perpetrated by the patient. By the way, restraining has to be the last resort. The first step is to call for help by pressing the alarm button attached to your body.”

10 DAYS, NO TREATMENT — 10 DAYS OF NOTHING

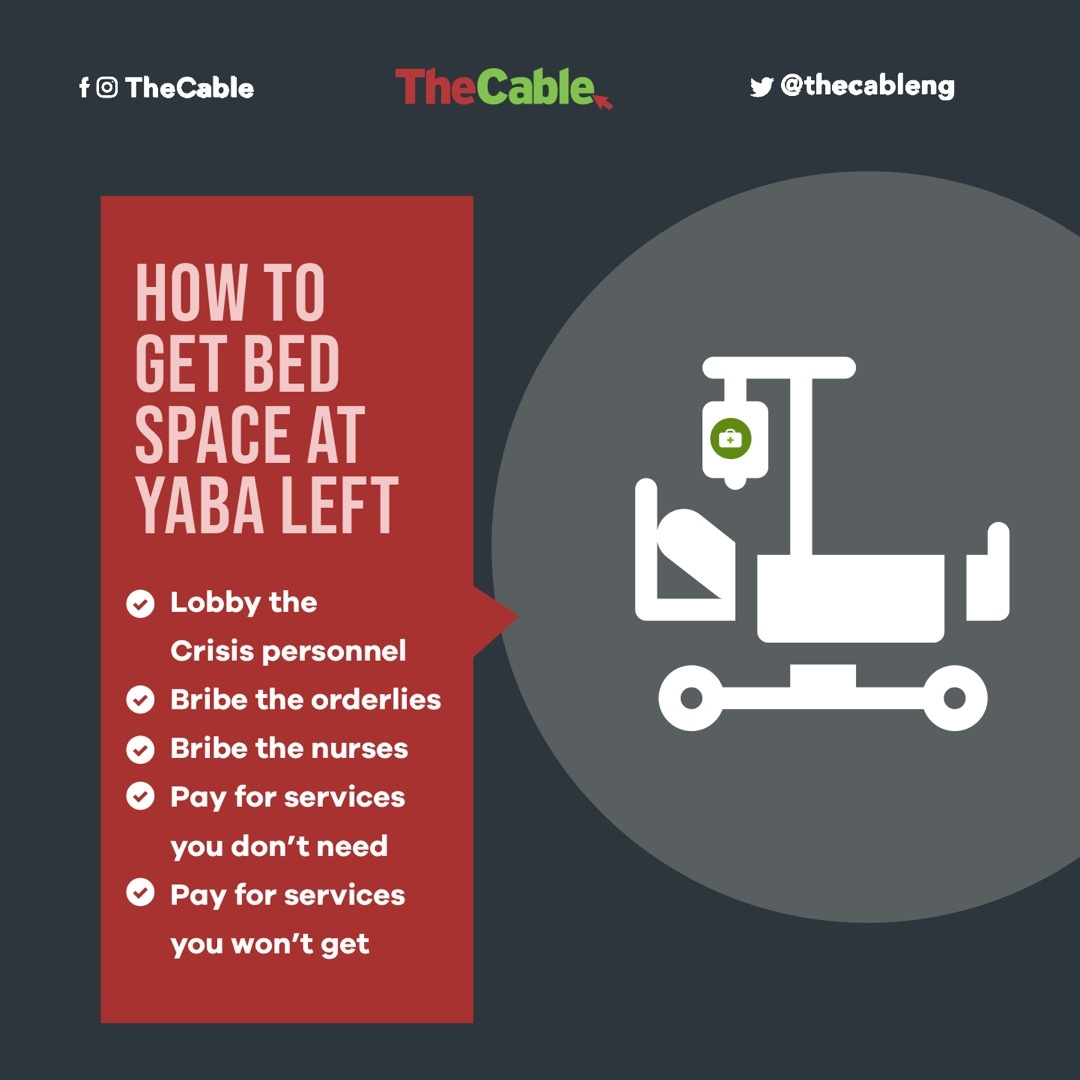

On the day I arrived Tolani Asuni, before I slipped into the hospital-approved pyjamas and I was stripped of all my personal possessions, I asked the nurse on duty exactly what kind of treatment to expect since the doctors had exempted me from drugs and injections. “Therapy,” she answered me. “Group Therapy (GT) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).”

Held every working day of the week, the GT allowed all drug inpatients to come together to learn from one another’s mistakes. It was led by a firm but likeable bald-headed male doctor, who is an alumnus of the University of Ibadan, plus a fair-complexioned female psychologist who spoke with a thick Igbo accent and was generally considered by patients as brilliant but puffy. The GT came with the total N120,000 admission package.

But I would need to pay an extra N10,000, the nurse told me. This was separate from the admission fee, and this was regardless of the initial charge of N20,000 for drugs that the hospital knew I wouldn’t need but made me pay for. If I paid the N10,000 early enough, the nurse explained, I would get an early CBT date. So I paid in cash right there — before I stepped into the room allocated to me in the ward.

I would soon find out my CBT had been scheduled for December 31 — six full weeks after the commencement of admission. Effectively, this meant that the hospital was offering me no single condition-specific treatment or therapy. I spent the last five days of my stay pestering the nurses, doctors and psychologist for a readjustment of my CBT date. “My brother, it’s not our fault,” the Igbo-accented psychologist told me one day. “Tell Buhari to employ more people.”

Until my discharge on the 10th day, I hadn’t experienced one single session of CBT. Just before signing the papers for my release as pressed for by my team, Dr. Ojo, the consultant in charge of my case, said: “Let me emphasisie that we have not released him so that you can take him away permanently. He should be coming from home — because we know that we haven’t done anything on him. Up till now, he hasn’t even been attended to at this ward yet.”

For a drug patient that hadn’t entered psychosis, that had never experienced it, that wasn’t placed on drugs or injection, this is inexplicable, actually. Ten full days of “doing nothing” on a patient who already made full payment!

STAFF SHORTAGE, GHOST WORKERS, LOPSIDED RECRUITMENT

In truth, the hospital was experiencing an acute shortage of nurses, doctors and psychologists. Only two psychologists served a patient population that often hovered around 535 inpatients and approximately 800 outpatients. Working in shifts, the nurses number just under 200, but they were evidently overworked. Ideally, two of them ought to be on duty in the morning, and another two at night. This seldom happened. Oftentimes, two worked in the morning and one in the evening, or one in the morning and two in the evening.

In addition to the general shortage of nurses, there is also a shortfall between the number of nurses on the hospital’s books and those actually operating the shifts. For a number of reasons.

“People retire every year, people get transferred, people die, people travel. If today there’s an opportunity for 50 nurses to travel, they won’t even wait till tomorrow,” a nurse said on phone when asked to explain the inadequacy of nurses.

“All these deplete the workforce. Even I myself, if I get an opportunity to travel for a course for two or three years, I will go. But my name will remain in the employ of the hospital. There are people benefitting from such arrangements, which, of course is their absolute right. It’s in-practice training, and they return to the hospital better equipped for the job.”

Sometimes, nurses are seconded to other institutions to offer stability for a period of time, and they’re not replaced during their absence. One or two staff may even be hospitalised long term, yet no one is employed to fill in for them. Instead, their work is spread among the remaining staff.

“At every point in time, there is avenue for many people not to be on ground,” he added. “And the expectation of the government and the hospital management is on the nominal role. However, statutorily, everyone on the nominal role cannot be on the ground.”

According to the nurse, these challenges are nothing new, not peculiar to the neuropsychiatric hospital, and easily solvable with constant reemployment and futuristic planning.

“Since October this year, a serious administration would have sat down to say, how many people are retiring next year: how many nurses, pharmacists, doctor, cleaners, and so on? How many staff relocated abroad or travelled for trainings?” said the nurse.

“Then you can factor all these information into your recruitment plan for the next year — even if not to expand, at least to maintain the current staff strength. The solution is to employ more and plan ahead.”

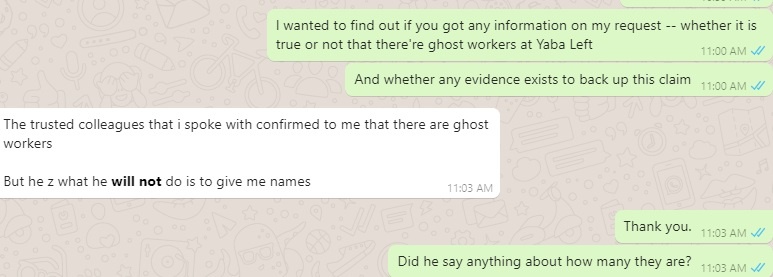

The problem, though, is anything but that simple. Even if nobody wants to talk about it, the scourge of ghost working is an open secret at the hospital. The nurse quoted above admitted that he was “aware that there were ghost workers” at the hospital, but he said would rather not talk about it as he was, by official duty, not in a position to obtain formal evidence.

He was the second Yaba Left nurse contacted during the search for evidence. But unlike the first, who downright turned down a request to speak, he sent us the contact details of a nurse who “certainly can give you evidence”. “I don’t know if she will want to speak with you,” he warned. “But if you’re able to, trust me you’ll get a clear picture of the number of ghost workers in the system.”

At exactly 11:02am on December 23, I called the nurse, a female. She asked that I call back at 4pm. When I did at exactly 4pm, her initially encouraging countenance had become unfriendly “Please I’m still very very busy [sic]; I’m not yet at home.”

Asked what time I could call back or if she didn’t want me to at all, she replied: “You may not bother at all. I’m extremely busy presently.”

A mini-breakthrough came through a fourth nurse based in the South-South, who promised to speak with a colleague of his at Yaba Left. The answer, when it came via Whatsapp chat, read: “The trusted colleague I spoke with confirmed to me that there are ghost workers. But he said what he will not do is give me names.”

Beyond ghost-working, there is a litany of admin issues to be resolved at Yaba Left. The hospital’s consultant-resident doctor ratio is thought to be approximately 2:1; meanwhile, standard practice is 1:4! This anomaly, I understand, has festered this badly because lots of consultants who should have exited the system are being retained on curious grounds. Aside the belief in some quarters that probably as many as 500 nurses are in the hospital’s records while roughly half do the work in practice, it is interesting to note that there are approximately 1,000 admin staff on paper — more than the number of nurses and doctors combined! There are two psychologists on drug ward but about 12 in the entire hospital, which is still grossly inadequate. There are only four occupational therapists even though the hospital runs a school of occupational therapy.

There have also been complaints of deducted but unremitted tax from staff income, plus hushed talks about the nature of ongoing projects, the identity of the contractor and the financial value of the contracts.

‘I DON’T TALK ON PHONE’ — YABA LEFT CMD

On Friday January 17, 2020, I contacted Dr. Oluyemisi Ogun, the Chief Medical Director of the hospital, for her response to my findings. I had only mentioned “the quality of food that patients eat and understaffing, inadequate number of nurses possibly due to…” when she interjected: “Who gave you the statistics? Who is complaining to you? If you have anything, come and see us, please.

“When I see you face-to-face… I don’t talk on phone. If you have any problem, then come and then we see, and then you can see the facts yourself on ground. Thank you.”

MAKING YABA LEFT RIGHT

As with all other government-run hospitals, funding is one of the major impediments to the smooth operations of Yaba Left. Despite joining 20 other member nations of the African Union to sign the 2001 Abuja Declaration agreeing on the allocation of 15 percent of federal budgets to healthcare, Nigeria has never met the target, and has in fact always fallen short of even the halfway mark. Only 3.95 per cent of the 2018 budget was reserved for the Ministry of Health; it was less than 2 per cent in 2019 and 4.14 per cent in 2020. The highest percentage since the declaration was the 5.95 per cent of 2012. Meanwhile, seven countries — Rwanda, Botswana, Niger, Zambia, Malawi, Burkina Faso and Togo — have all met the Abuja target.

The neuropsychiatric hospital at Yaba — and indeed other government-managed hospitals — can’t offer quality healthcare to the people with continued underfunding, especially with an ever-increasing patient population that rose by 51 per cent from 40,502 outpatients and inpatients in 2018 to 61,154 in 2019. However, the finance-induced problems of tertiary hospitals nationwide are always complicated by “corruption and all that stuff”.

In the 2017 budget, for example, N9 billion was specifically allotted to the purchase of radiotherapy machines for some teaching hospitals (and another N117 million was also budgeted for cancer-related issues). At that time, the most expensive linac radiotherapy machines cost between of $750,000 and $1.5million (between N228 million and N456million, at the then CBN rate), excluding associated costs such as the vault that will house the system, treatment planning and oncology information system software, lasers, and other accessories. Still, the government bought only one RT machine — for the National Hospital! And this is despite knowing there were only four functioning radiotherapy machines all over the country at the time to serve an estimated 200million Nigerians, The question, then, is: where is the rest of the N8bn?

One big strength of the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital Yaba is the sheer passion of majority of its workforce. There are many Dr. Ogunlowos and Dr. Akingbolas at the hospital — medical staff who are incredibly committed to the profession but are becoming increasingly pessimistic about the Nigeria project.

“Many of us love this job to bits but our frustrations with the system pushed us out of the country,” said a former staff of the hospital who now practices in the Canada. “I hope the government addresses Yaba Left’s problems because the more the doctors get frustrated by the system, the more they leave and the more the number of untreated or shabbily-treated mentally-ill patients walking the streets. That can’t be good for Nigeria.”

Those sentiments were shared by the UK-based Nigerian nurse. “I probably would have beaten that boy myself if I was still in Nigeria,” she said.

“Over there in Nigeria, it isn’t that professionals are inherently civil. But here in the UK, we have a system in place that punishes unprofessional behaviour. That way, civility is inculcated by sheer force of discipline. Look at the idea of CCTV camera, for instance! We can do it in Nigeria, too, if we really want to.”

Editor’s Note: This is the second and final of a two-part series. You may read Part I here.

This investigation was published with collaborative support from Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation and Business Day.

Add a comment