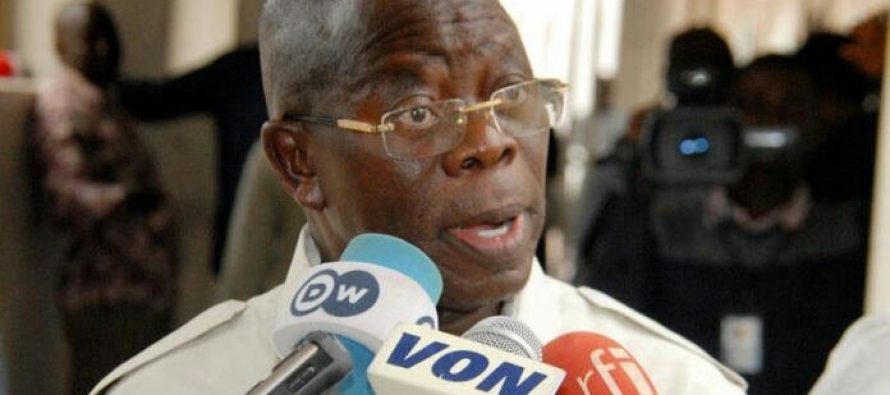

PIC 1. From left: Senate President Bukola Saraki; Acting President Yemi Osinbajo; Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN), Justice Walter Onnoghen and his wife Nkoyo at the Swearing-in of the CJN at the Presidential Villa in Abuja on Tuesday (7/3/17)

01858/6//7/3/2017/Callistus Ewelike/NAN

Nigeria’s laws, institutions and processes are, for the most part and with some exception, defined by two inherent flaws. One is the flaw of the time warp and the other is the flaw of institutional cross-dressing.

Let’s begin with the time warp. Many of the essential norms and institutions that still govern the country that now exists as a democracy have their origins in Victorian England and were transported to Nigeria on the backs of either unaccountable colonialists or the bayonets of unelected soldiers. With colonialists, we were subjects incapable of being citizens; with soldiers, we became citizens without a country to call our own. Colonialists treated us as morons; soldiers presided over a Republic of Zombies. Yet, these norms and institutions designed to govern morons and zombies for the most part continue to regulate much of our affairs around the country.

These origins organically lead to a second flaw – the problem of normative and institutional cross-dressing in which laws made for non-deliberative, autocratic systems continue to be applied to govern the essential processes of deliberative democracy. Nearly always, this cross-dressing is an ill-fit but the reflex that has survived martial rule learns how to “obey the last order.”

The underlying sclerosis that afflicts the administration of justice in Nigeria owes its origins to these two flaws. In our federation of 36 states, however, one state has led the process of weaning itself of this illness and in persuading the rest of the country to discover virtue in doing so. That state is Lagos. In the period since the country returned to elective government 20 years ago, it has under the professional leadership of its Ministry of Justice, orchestrated a set of carefully calibrated reforms to re-configure the normative and institutional foundations of its governance for the challenges of deliberative democracy. In this spirit, Lagos has pioneered many reforms including the Administration of Criminal Justice Law 2007, amended and re-enacted in 2011 (Nigeria copied this in the Administration of Criminal Justice Act, 2015); the Coroners Law 2007; the Criminal Law of Lagos State 2011; and the Lagos Court of Arbitration, launched in 2012.

Advertisement

Ministering Justice,

In Ministering Justice: Administration of the Justice Sector in Nigeria, Olasupo Shasore, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), and Akeem Bello, a legal scholar, narrate how Lagos undertook and achieved these and many more path-breaking legal and institutional reforms

The setting and the authors are hardly surprising. With over 11% of Nigeria’s population, Lagos is the most populous State in Nigeria. But with a mere 3,577 km², Lagos is also by far the state with the smallest land-mass in Nigeria. Lagos is the site of the former colony (the rest of the country was “protected territory”). The oldest and first institutions of modern law enforcement and dispute resolution began in Lagos and the first lawyers in Nigeria also practiced in its territory. Lagos also harbours over 60% of Nigeria’s industrial investment and about two-thirds of its commerce. In simple terms, institutional innovation and adaptation are existential imperatives for Lagos State.

Advertisement

The authors are well qualified to tell this unique story. For four years beginning in 2007, Mr. Shasore was the Honorable Attorney-General (HAG) of Lagos State and Commissioner for Justice. He was preceded in this office by Oluyemi Osinbajo, another Senior Advocate and law professor, who currently serves as Nigeria’s Vice-President. As Attorney-General, Mr. Shasore worked closely with his co-author, Dr. Akeem Bello, who was assigned to the Attorney-General’s office as the Senior Special Assistant to the Governor of Lagos State on Public and Constitutional Law. The Governor during this period was Babatunde Raji Fashola, another Senior Advocate and currently a Minister in Nigeria’s federal government. After their combined time at the office of the HAG, Mr. Shasore and Dr. Bello went on to serve until 2015 as Chairman and Commissioner, respectively in the Lagos State Law Reform Commission. Back at the office of the HAG, they were succeeded by Ade Ipaye, another distinguished law teacher, who currently also serves as the Deputy Chief of Staff to Nigeria’s President.

In a narrative that unfolds as both memoir and manual, the authors of Ministering Justice tell a story of two decades of innovation, experimentation and continuity in engineering the institutional adaptations required by a mega-city state. It is organized into twelve chapters that address several challenges aspects of the transformation of laws and institutions of Lagos State, including the reforms of magistrate’s court system, criminal procedure, the coroner’s system, criminal law, governance of law and order, and commercial dispute resolution. It also illustrates other less well known aspects of the brief of the HAG as adviser to government, member of cabinet, public officer, manager, strategist for government, litigator and protector of the public interest.

In Ministering Justice, the authors, showcase the stories of the emergence and operation of tools like the Criminal Case Tracking System (CCTS); the Crime Data Register (CDS); the Forensic Centre for Criminal Justice, and the Multi-Sector Working Group (MSWG) on Pre-Trial Detention. In doing so, they demonstrate the enormous value adding possibilities of a capable HAG in a consequential cocktail of re-imagined norms, institutions, processes, management tools and partnerships that make the incremental progress and protection of our communities possible.

Ministering Justice is a narrative of multiple cadences. Its highlights are subliminal. First, the authors demonstrate the significance of the office of the Attorney-General in guaranteeing public good and envisioning the institutional arrangements required to secure it. One clear highlight of the book is the story of how the office of the HAG was tasked to lead arguably the most radical and far reaching urban renewal project undertaken by Lagos State in the past twenty years – the Oshodi Market renewal project which began in 2010.

Advertisement

This leads to the second major highpoint of the narrative: it powerfully makes the point that effective public service and leadership requires not just capable minds but also a thoughtful team. Many will be struck by the fact that the onset of the Oshodi Market renewal project was preceded by nine months of reconnaissance and preparation at the end of which the most critical decision was the choice of what time in the year to begin it. The government thoughtfully settled for the 4th of January, a time when “economic activities are usually at the lowest ebb…. with many businesses just about to open after the Christmas and New Year holiday.” The pivotal decision here was the strategic call by the Governor, Raji Fashola, to define Oshodi as a law and order problem not as a contract waiting to be parceled off. Once that call was made, it’s easy to see why and how the HAG had to lead it.

Thirdly, underlying the narrative of Ministering Justice is a lesson about professionalism that every legal professional and public officer should take to heart.

When Justice is in Crisis

The release of Ministering Justice coincides with a moment of considerable crisis for Nigeria’s politics and institutions of the law. The decision of President Buhari to suspend the Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN) within the immediate horizon of an election season naturally divides opinion. It also calls into sharp relief the role of an Attorney-General, which is itself the theme of Ministering Justice.

Advertisement

The known facts do not allow for much speculation: A petition dated 7 January was addressed to the Chairman of Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB) complaining about what appeared to be allegations of substantial omissions or discrepancies in the asset declaration of the Chief Justice. The Chairman’s office stamped receipt of the petition on 9 January. On the same date, 9 January, the Attorney-General apparently addressed an ex-parte application to the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT) asking it to order the Chief Justice to vacate office and for the President to swear in the next senior-most Justice of the Supreme Court in his stead to act. With this time-line, there was no question of verification of the assets forms in issue or investigation of the petition received on 9 January before a referral to the CCT. There was just no time for that.

A charge was only preferred against the CJN on 10 January. Things moved very quickly thereafter. On 23 January, the CCT sat in open session and upon being informed that there was an order of the Court of Appeal requiring it to preserve the status quo, appeared to adjourn. Two days later, it appeared, however, that sometime after adjourning on 23 January and on the same day, the same CCT somehow granted the ex parte application of 9 January on its terms. The only problem is that the application was not moved, the underlying petition was not investigated and the charges framed upon it were yet to even be taken on arraignment. Those who support the steps taken by the President dismiss this narration as of no consequence. But these facts do in fact matter.

Advertisement

The fall out of is that a free-for-all political argument has broken out, naturally garlanded, as is our wont in Nigeria, with choice epithets and inspired invective. In this trade in abuse, many things have been lost. There should be no argument over whether or not a Chief Justice should be investigated for alleged infractions of public integrity standards. S/he is not above the law. But that is a non-sequitur. The issue is what happens when that is the situation.

It should go without saying that any allegations along those lines should be investigated and if infractions are found, the law should be applied firmly. The problem is that in this case, an investigation has not taken place and the law has been abused by the most powerful politician in the country in circumstances that make it impossible not to ascribe partisan political animus to him. That is damaging. Many people argue that the Nigerian judiciary is corrupt. Complaints of rampant judicial corruption are in fact older than post-colonial Nigeria. In the immediate decade after the Amalgamation, Sir Kitoyi Ajasa, one of Nigeria’s earliest judges, was said to have been preferred to the bench as an act of craven, colonial cronyism. The way to deal with these allegations is not to appropriate the low ground in high political season.

Advertisement

There are many objections to what the President has done and to how he did it. For one, judicial appointments, like removals, involve all three branches of government and demonstrate the coherence of the basic structure of the constitution in separation of powers. The CCT and CCB are Executive organs. By relying on them exclusively in this process, the President violated this basic structure of the Constitution. Second, he procured this violation through the deployment of sovereign vigilantism. It is a basic canon of dispute resolution that parties having subjected themselves to a process cannot return and take the laws into their hands just to guarantee outcomes that they want or like. That is exactly what President Buhari did. By so doing, the government loses the high ground in a country with serious rule of law crises, to tell citizens to respect laws or honour institutions that it treats with unconcealed disdain. Third, the President compromised the integrity and independence of the CCB and the CCT. Many say the allegations against the CJN are grave. Indeed, they are. And precisely because they are, they deserve to be disposed of through due process for without that, we will never know the facts or be assured that the allegations have weight. The question will surely be posed: if the government was so sure of its allegations, why was it in a haste to end-run the process? This leads to the fourth point, which is the moral burden of claiming to fight corruption through mechanisms of hypocrisy that selectively use laws only when they are deemed favorable.

Above all, however, the argument is that the National Judicial Council (NJC) headed by the Chief Justice could never be trusted to discharge its burdens in investigating him. This is an insult to all Nigerians – including people like the co-authors of Ministering Justice and the impeccable public servants who have led the Lagos State Ministry of Justice since 1999 – who show in their own modest examples recounted in the book, how much of a fallacy this is. In any case, even assuming this to be the case, would it not have made sense to allow the NJC to show itself a failure before resorting to sovereign vigilantism?

Advertisement

Even after procuring the ex-parte order from the CCT, the President had the option of notifying the NJC about the development in order to trigger the exercise of its constitutional role. He chose not to. Rather he exercised non-existent powers to summon a Vice-Chair of the NJC to assume the role of the Chief Justice without the knowledge of the NJC. The Justice tapped, himself a judicial veteran, allowed his ambition to outstrip his experience, intellect and ethics, a terminal vice that hardly qualifies him for consideration as Chief Justice.

Casual Locusts

Unsurprisingly, the authors of Ministering Justice devote their final chapter to address wider challenges of Nigeria’s justice system, which they elegantly describe as “locusts, clogs and fetters”. Ministering Justice is a tale of how they set about undoing all these in Lagos. It’s also a manual for how the rest of Nigeria can do the same. They argue a compelling case for a reform of judicial appointments and a return to professionalism and ethics. At any other time, their undoubted expertise should ordinarily afford ample authority to their suggestions. The current climate elevates their suggestions to the status of prescription.

In this case of the crisis caused by the suspension of the CJN, the real damage has been caused by the appearance of unprofessionalism on nearly all sides. The worst case is the casual and unpardonable perfunctoriness of the Honorable Attorney-General of the Federation (HAGF). In approaching the matter the way he did, he assures that his principal will be dogged long after he has left office of by undeniable accusations of abuse of power. The underlying message of the memoir in Ministering Justice is that a HAG cannot afford to expose his or her principal to the damage of such toxic legacy. In the manual in the book, the authors show how this can be done. It’s a companion for everyone interested in how the law can serve the public interest in and beyond Nigeria. Many more who have verifiable outcomes to show for their time in public service should follow the combined examples of Supo Shasore and Akeem Bello and document their records for posterity.