BY ELIZABETH CHISOROM CHUKWU

Discrimination is a construct woven into society through ideas, stories, language, and environments—but children are not born into the world with these biases. Their early perspectives are open, accepting, and unfiltered. For a child, differences in skin colour, age, and social background are simply part of the world, as intriguing and benign as differences in flowers in a garden.

Yet as they grow, many become aware of invisible boundaries around these differences, influenced subtly or overtly by their surroundings. The concept of “us vs. them” is absorbed through experience, observations, and, more significantly, through what they are taught by the adults who raise them, the communities surrounding them, and the institutions they grow up in. The gradual internalisation of discrimination is a learned process, not an inherent trait.

Upon interaction with them, many young children show no innate prejudice; these tendencies are imprinted as they learn to distinguish social boundaries that define “in-groups” and “out-groups.”

Advertisement

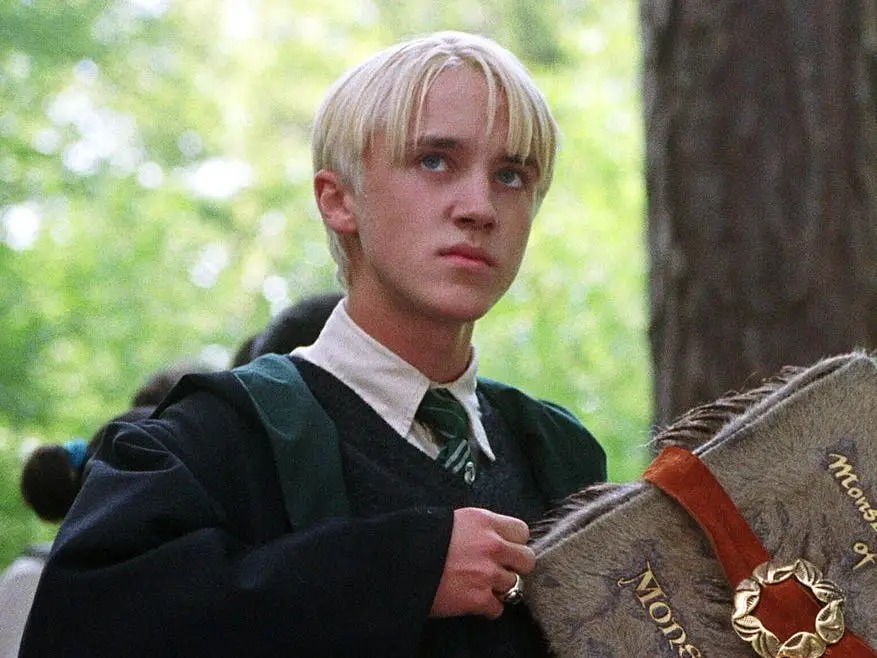

In J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, we encounter a stark fictional example of this phenomenon in the character Draco Malfoy. Draco’s worldview, moulded by his pureblood family’s deep-seated belief in their superiority, mirrors how learned discrimination operates in real life.

His family’s views on blood purity, equating it with intrinsic worth, guide every part of his world: Draco learns early on to view muggles and muggle-born witches and wizards with disdain, to feel justified in his prejudice, and to think of those outside his bloodline as lesser.

This ingrained ideology becomes part of Draco’s identity, not because he critically examined it or came to it by independent thought, but because it was simply the reality he inherited. This makes him a product of his environment—a reflection of what he has been taught rather than an innately prejudiced person.

Advertisement

From his first introduction, Draco’s antagonism toward Harry Potter is complicated. Draco initially admires Harry, who is, after all, a celebrated figure in the wizarding world. Their first meeting on the train to Hogwarts sets up the potential for an alliance; however, Draco’s casual comments about blood purity make it clear that his values and beliefs are already deeply entrenched, ones he assumes Harry, as another magical “elite,” might share. What Draco doesn’t anticipate is Harry’s inherent distaste for such prejudice, especially having been raised in an abusive environment.

Harry, however, is far from a blank slate himself. He has been warned by Hagrid, a trusted figure, about the house of Slytherin and those who belong to it, which includes Draco. “There’s not a single witch or wizard who went bad who wasn’t in Slytherin,” Hagrid tells him, instilling in Harry a wariness that becomes immediately relevant as Draco introduces himself with his casually prejudiced remarks. The instant tension between Harry and Draco, built on misperceptions and warnings from authority figures on both sides, reveals how initial impressions and prejudice can block the chance for understanding.

Reflecting on this tension, one can’t help but wonder how different things might have been if Harry had been sorted into Slytherin, as the Sorting Hat initially suggested. What would have happened if Harry and Draco, united by their house identity, had learned to understand each other’s backgrounds and worldviews before their differences solidified into unshakeable antagonism? Instead, they are sorted into opposing houses, and their interactions from that point on are laced with conflict and distrust, even as circumstances occasionally force them to work toward common goals.

This “what if” scenario illustrates a most basic truth about discrimination: much of it is sustained not by open conflict but by a lack of communication, where people are confined within echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs. Even Harry, a protagonist who fights for equality and justice, is guilty of harbouring his bias against Draco and Slytherin, largely because he has been primed to see them as an “enemy.”

Advertisement

The psychology of discrimination is further complicated by the understanding that once a belief becomes part of a person’s identity, it resists change. Humans tend to cling to their perspectives; it is uncomfortable and threatening to acknowledge that something we have believed, perhaps our whole lives, might be fundamentally wrong. Changing these beliefs requires humility and openness, often in short supply. This resistance is mostly driven by ego—the psychological armour that protects our identity and convinces us we are “right.”

Draco’s behaviour toward Harry is often rooted in this need to assert his superiority, and each time Harry reacts with hostility, Draco’s views become more ingrained. This dynamic is common in real-world conflicts: as each side becomes more entrenched in its position, the gap between them widens, and the potential for genuine dialogue diminishes.

In these situations, many believe bridging the gap should be the responsibility of the more privileged party, rather than the oppressed. It is not, for example, the responsibility of people of colour to educate those who discriminate against them, nor should women bear the burden of explaining why sexism is harmful.

Such dialogues, if they are to happen, ideally involve allies or individuals who are similar enough to avoid triggering the defensive barriers that often arise in debates. In the case of Draco, perhaps a different Slytherin peer—one who was sympathetic to muggle-borns—might have been more successful at opening his mind than Harry could ever be. When facing discrimination, many of us react with anger, and while this response is valid and justified, it can also be a barrier. A constructive dialogue requires not only courage but also patience. It’s about knowing when and how to engage in a way that doesn’t necessarily compromise one’s beliefs but doesn’t force the other person into an automatic defensive posture.

Advertisement

The tragedy of Draco’s character is that he remains trapped within his family’s worldview for so long, never fully liberated from it even as he begins to question its validity. But despite the bleakness of his situation, there are moments where the potential for change surfaces. By the end of the series, we see glimpses of his internal struggle, especially as he faces the moral consequences of his allegiance to Voldemort.

These hints suggest that unlearning deep-seated prejudice is possible, though it often takes significant, even life-altering events to shake people out of their inherited beliefs. Real-world analogies are easy to draw here: people who grow up in environments filled with prejudice may only begin to question these values when they form close relationships with people from the communities they were taught to despise or encounter moments that force them to recognise the humanity they share.

Advertisement

Achieving a more inclusive society requires both patience and strategy.

While not everyone can or should take on educating those with discriminatory beliefs, each interaction offers a potential—if faint—opportunity for change. This doesn’t mean always accommodating; it means understanding that true, lasting change in people’s beliefs rarely happens through confrontation or shaming. Instead, change is often slow and subtle, emerging over time as individuals have space to question, reflect, and eventually, revise their ideas.

Advertisement

In this, the story of Draco Malfoy offers a cautionary tale but also a glimmer of hope. For if even he—a character whose life was steeped in prejudice from childhood—can find moments of doubt, moments that challenge his worldview, then perhaps there is potential in everyone to unlearn, to grow, and to understand.

Elizabeth Chukwu is a corps member at Nigeria’s Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, Abuja; she writes via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.