BY CESARE ADENIYI-MARTINS

We are living through the last ages of urbanisation. In 2018, the United Nations estimated that 78 million people annually relocate to cities across the globe, 58 million of which are from Africa and India.

MOST POPULOUS CITIES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

With over 17 million inhabitants, Kinshasa is one of the most populous cities in Africa, and its nation-state, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is saddled with inefficient government institutions. It is plagued with civil war and enormous infrastructural deficits. Dar es Salaam in Tanzania also has been hammered with a rapid urbanisation rate, with some estimations predicting a population of 74 million by 2100. Tanzania is one of the poorest nations in the world with low human capital development, poor level of productivity, and high rates of unemployment. Lagos, Nigeria has over 22 million residents with an astounding trajectory towards 90 million residents by 2100. Considering the alarming rate of urbanisation, what is the future of our cities? Do they have the economic and governmental capacity to support these extreme populations?

Advertisement

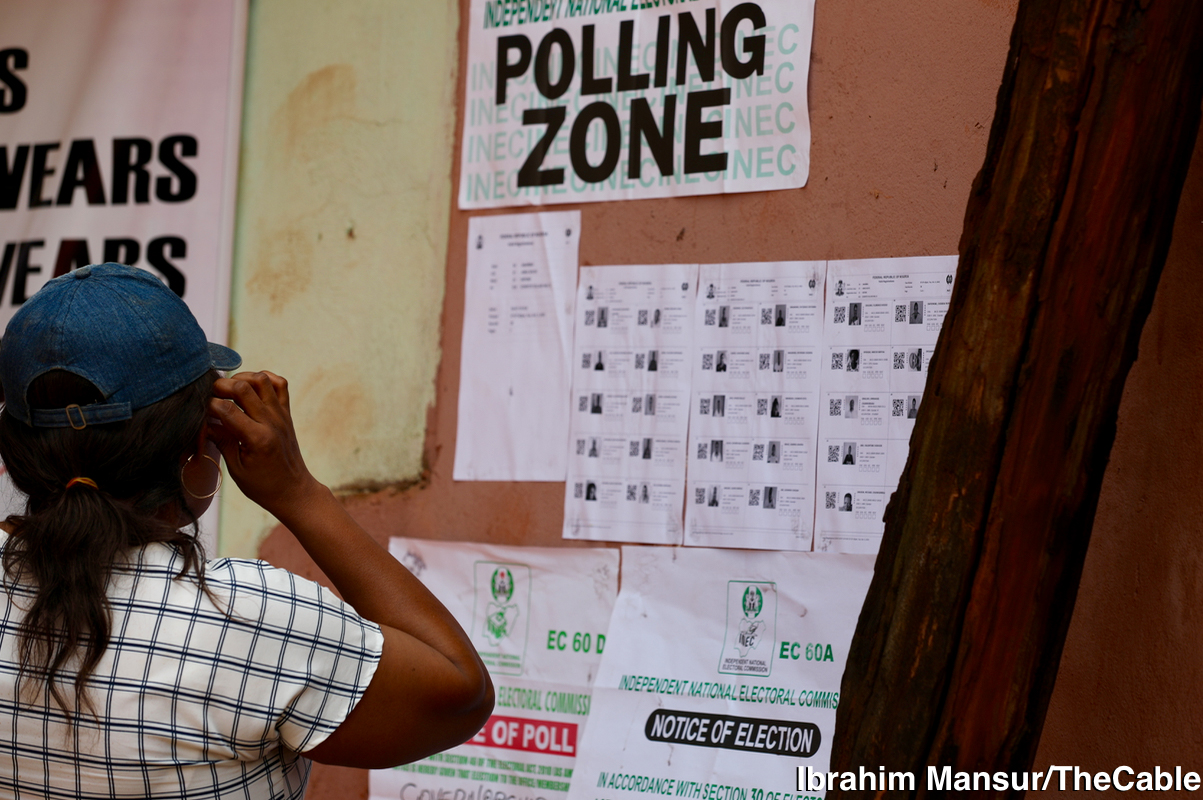

NIGERIA’S HEALTH OF GOVERNANCE

Nigeria is known for its economic potential in SME output, technology solutions and business process outsourcing, but, despite this potential, extreme poverty remains in the country. Dysfunctional governance is a result of the country’s poor business environment caused by gaps in infrastructure, stifling laws, and regulatory constraints. The World Bank’s 2020 ease of doing business index ranks Nigeria as 131st in the world, which places it in the bottom half of ranked countries. This is alarming, as the World Bank in 2006 estimated that the value of institutions, measured by rule of law, comprises 48% of the world’s wealth. There’s a huge indication that emerging markets need to open up their economy to the World through deep governance reform and entrepreneurial initiatives to create revolutionary models to solve critical issues that are inherent in our institutions. Our cities’ futures should be determined through an institutional arrangement that is adaptable to change and innovation, like Shanghai’s, Shenzhen’s and Dubai’s — one that creates inclusive access and competes for the best social infrastructure, legal systems, and economic liberalisation models for sustainable growth.

CHINA ADOPTED ECONOMIC FREEDOM

Advertisement

Shenzhen

An early example of economic freedom ideas is Hong Kong, a city with a sovereign government. It served as a British colony before it was relinquished to China in 1997. Hong Kong was an economic and financial gateway to the western world with trade liberalisation and sophisticated dispute resolution, which, through its economic dynamism, had powerful spillover effects in mainland China. People came to Hong Kong to earn a living and then spread the wealth to other parts of China. China’s then leader, Deng Xiaoping, saw this potential and replicated the model by implementing SEZs in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen. In the 1970s, Shenzhen was known for its agrarian economy with about 310,000 inhabitants. In May 1980, the city of Shenzhen was granted the status of an SEZ – the first in mainland China. Its population grew to about 4.3 million people in 2000, and now has over 12 million residents with economic activity centred around manufacturing, shipping, logistics, technology, and innovation. Shenzhen is one of the most economically active cities in China with 2.1 million people employed in the manufacturing sector alone. The World Bank estimated that China lifted over 800 million people out of poverty since 1978 through economic openness.

THE UAE ON RESILIENT INFRASTRUCTURE AND COMPETITIVE REGULATIONS

Transformational leaders built Dubai into a world-class city by enabling economic freedom. Sheikh Rashid pioneered a movement for the transformation of Dubai from a cluster of villages to a modern city. He was behind some major infrastructure projects like Port Rashid in 1972, the Dubai World Trade Centre in 1978, Port of Jebel Ali, Al Shindagha tunnel in 1975, Dubai Dry Docks, and waterways, among others. The discovery of oil provided a source of revenue to fund these public projects. In 2004, the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) was founded, which became a catalyst for growth. It is a special jurisdiction where financial services thrive. In the zone, there are more fiscal incentives, which increase the ease of doing business. Dubai’s legal system utilises British common law for commercial cases, which provides a solid framework for business litigation. This attracts large corporations and investors, as they can rely on Dubai’s courts to uphold trade and financial contracts. In 2018, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) attracted the highest investment in the entire MENA region for services enabled economy This economic growth has been so significant that it has reduced the UAE’S economic reliance on oil. Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the current Prime Minister of the UAE, is planning on diversifying its power generation primarily towards renewable energy and making the country completely independent of oil by 2050.

ECONOMIC ZONES AND CHARTER CITIES

Advertisement

Various places in the world are establishing special economic zones. According to UNCTAD, there are over 5400 special economic zones in the world. Special economic zones (SEZs), are jurisdictions with reduced regulations and improved fiscal incentives aimed at fostering a sound business environment and attracting foreign investment. SEZs focus on a specific industry with high growth potential and occupy a small landmass.

Charter cities are similar to SEZs, but they expand the concept by creating a blank slate for commercial law where an independent governing body is able to establish a new set of rules separate from those of the host nation. Its attributes include private administration, devolution of authority, and an alternative dispute resolution system. Charter cities focus on large geographical areas with multiple industries and broader economic bases where people can live, work, and play.

ECONOMIC ZONES ARE PRAGMATIC TOOLS FOR BORDER REFORM

Special economic zones provide opportunities for governments to adopt policies to serve as major testbeds for economic growth confined within geographical delimited areas. These procedures can later be implemented at the national level if successful instead of implementing nationwide policies towards sustainable economic growth that have yielded little or no results. One of the economic growth indicators that have often been overlooked is knowledge exchange between foreign businesses and domestic talents. Economic zones can serve as a cluster to improve the technical expertise of local talents which can be passed to their immediate communities. Economic zones can create more employment opportunities thereby reducing the problems of poverty and insecurity in our society. Economic zones can reduce the deficit in social infrastructure, promote regulatory arbitrage and promote competitive governance among cities that are implementing them.

Advertisement

CHARTER CITIES ARE CLOSEST ALTERNATIVES TO DYSFUNCTIONAL GOVERNANCE

In recent years, there has been an advancement in the ideas of charter cities as an economic tool to address these issues. Charter cities are the nearest proof of concept to special economic zones and extend their concept by building a full-fledged city from scratch which solves the problems of the high rate of urbanisation. They provide environments that adopt best practices in commercial laws and regulations which would enable economic activities to thrive. Charter cities address the uncertainties that are inherent in the legal framework of a nation-state by adopting best practices for dispute resolution, creating a legal system based on trust, certainty, and reputation. They have the potential to create agglomeration effects in surrounding local communities which boosts the economic potential of these cities. In 2021, Charter cities were recognised as a tool to solve the sustainable development goals on poverty, economic growth and building resilient cities by the United Nations. If these economic tools can be properly implemented, the right social infrastructure would be in place to manage the rapid rate of urbanisation in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Advertisement

It is becoming necessary for the same entrepreneurial initiatives that are applied to tech to be applied to governance, which is a key determinant to the prosperity of a nation. Two notable entrepreneurs are already taking bold steps to build the value of institutions in their home countries through these ideas. Iyinoluwa Aboyeji is building a Talent city in Lagos, a charter city that is optimised for tech-enabled services, while Mwyiwa Musokotwane is also building Nkwashi, a 3,100 acres mixed-used city in Lusaka.

Political actors can help to build institutions that accommodate the experimentation of innovative ideas to solve society’s complex problems with deep governance reform, which can lead to fulfilling lives. Political actors should bridge the gaps between them and market actors in order to develop the right knowledge and quality policies, and they should engage the local level in policy reforms to achieve customised industrial arrangements for zone-based governance. They should resist the problems of rent-seeking and regulatory capture through public accountability and beneficial methods for their officials.

Advertisement

Cesare Adeniyi-Martins is the lead at Abelar, an organisation dedicated to promoting economic freedom and deep governance reform to create economic prosperity in Nigeria. He can be reached via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.