Suwaiba Abubakar, 25, hands a pack of sweets to two vaccinated children at a community in Sokoto south... Photo by Patrick Egwu.

BY PATRICK EGWU

For more than a decade, armed gangs and insurgents locally known as bandits have been attacking locals and farming communities in Nigeria’s northwestern region. There have been more than 13,000 insurgent-related deaths between 2010 and 2023, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data, a nonprofit which collects conflict data.

Growing attacks in the region are exacerbating health challenges facing local communities and settlements in the region, primarily affecting access to healthcare and responses to epidemics or other health emergencies.

But across Sokoto, one of the states in the region with cases of the circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus, local health officials are adopting a unique and practical solutions approach to reach hard-to-reach communities.

Advertisement

The Reaching Every Settlement (REST), an approach for reaching communities in conflict areas, is mostly adopted to access inaccessible settlements. The approach works by engaging community members from inaccessible communities through phone calls and other points of contact. Health officials invite vaccinators and community leaders from these communities to a safe and central location where they are trained, mobilised, supplied with immunisation materials and dispersed to vaccinate children in the conflict areas.

“Insecurity is a critical issue around polio immunisation in this area,” said Larai Aliyu Tambuwal, the executive secretary of the Sokoto State Primary Healthcare Development Agency, which adopts the REST approach and leads efforts to respond to the disease in the state. “This method has worked well for us in reaching these communities affected by conflicts.”

Tambuwal said members from conflict-affected communities are safer assets to use for immunisation drives than outsiders who may be seen by insurgents as intruders or spies for security agents.

Advertisement

“Most of the communities are totally inaccessible by outsiders. But the locals may be able to move more freely in their community than a visitor from elsewhere because they may be targets for attacks,” she said. She added that while they may not have access to supervise the vaccinations working in conflict areas, they collaborate and engage with traditional leaders in those communities to work as supervisors during immunisation drives.

The REST approach is one of the safest working strategies adopted by local health officials to reach inaccessible communities for immunisation, she said. When vaccinators face logistics challenges such as inaccessible roads to communities for example, Tambuwal said they make a trip to the Niger Republic, Nigeria’s border country to the north, located some 511 kilometres in order to have access to hard-to-reach communities.

“We are trying whatever we can to reach and immunise every child and make sure no one is left behind,” she said. “The insurgents also have children who are prone to contracting the disease.

That is why we are looking at strategies that may allow us to have some kind of interface to allow the children to be vaccinated.”

Advertisement

She noted the agency uses local vigilantes to escort vaccinators during immunisation drives for protection. She said sighting soldiers may have the bandits thinking “you are coming for a fight and you don’t want to escalate things and make it difficult for them (vaccinators).”

Tambuwal’s agency works with eHealth Africa, a leading health nonprofit, to provide vaccine tracking system devices to the vaccinators to help monitor their activities and locations visited. The geospatial tracking system application, which was first used in 2012, is used to monitor vaccination teams and report daily missed settlements based on the daily implementation plans of a campaign.

But the growing insecurity in the region means that vaccinators no longer use it while in the field as a safety measure, according to Tambuwal.

“If they go with that tracker and the bandits see them, they may feel they are coming to spy on them which may lead to violent attacks or abduction for ransom,” she said.

Advertisement

REDUCING VACCINE NON-COMPLIANCE AND HESITANCY

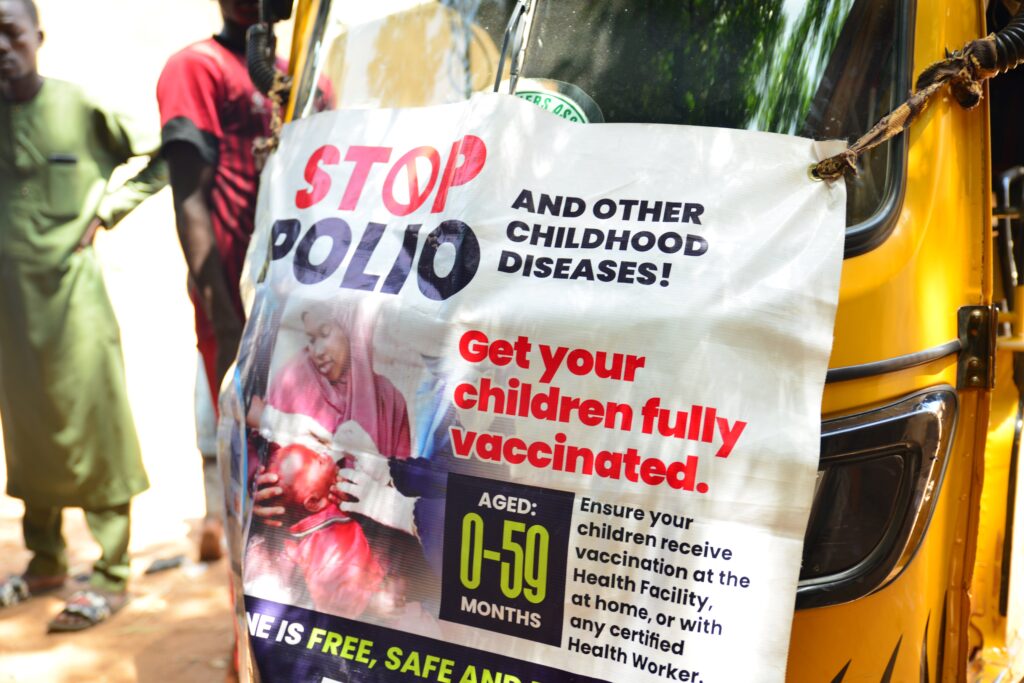

Back in September, Tambuwal’s agency in partnership with the government launched an outbreak response polio vaccination campaign in local communities for children aged 0-59 months old. Some 3000 vaccinators covering 23 local government areas in 24 wards and 1,876 settlements were engaged for the house-to-house vaccination drives.

Advertisement

The state recorded about 70 cases of the new strain of the virus between 2023 and 2024, but some successes have been recorded, Tambuwal said, noting that they have achieved 80 to 85 percent vaccination coverage for all eligible children. More than 1.4 million children have been vaccinated according to official data which is corroborated by partners such as UNICEF.

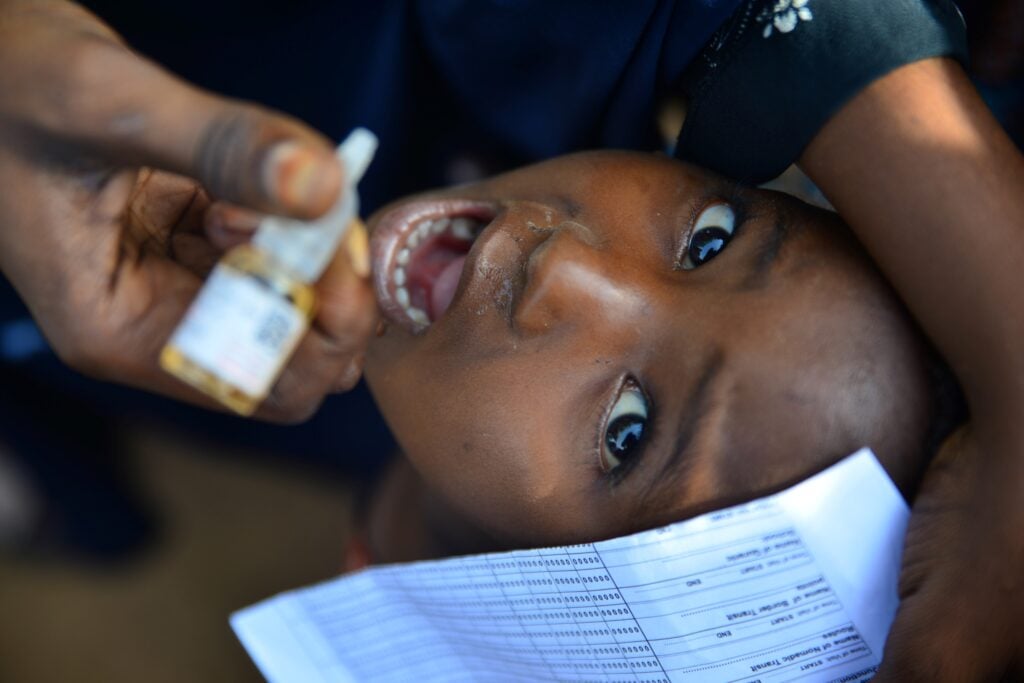

Suwaiba Abubakar, 25, is one of the thousands of vaccinators engaged in the immunisation campaign. She joined the immunisation team about four years ago and this is her third time participating in a polio vaccination drive this year.

Advertisement

During the vaccination campaign, Abubakar wakes up every day at 5 a.m. to get ready for the day’s vaccination activities. At 6:3 a.m. she leaves for the local hospital where she meets with her four-member team to pick up their vaccination materials and head out for the vaccination drives. Each vaccination team is made up of a vaccinator, an announcer, a recorder, and a community leader who is usually a representative of the community and acts as an interface between community members and the team.

Abubakar, who acts as the group’s supervisor, said vaccine non-compliance and hesitancy among community members is one of the common issues they face.

Advertisement

“I try to convince them and tell them (community residents) that the vaccine is safe and the immunisation of their children is important to protect them and their community,” she said, while inking the left finger of a vaccinated child. “I want parents to take part in all of the immunisations because it saves lives.”

During epidemics, vaccine distrust is prevalent in local communities across Nigeria. Previous cases of vaccine mishaps have affected the acceptance rates of vaccination programmes by local communities and residents.

One particular case stands out – a failed unethical clinical drug trial by U.S-based Pfizer in Kano state, another northwestern state some 465 kilometres away. One hundred children were given an experimental oral antibiotic after a meningitis outbreak in 1996 which led to the death of 11 children and a long legal battle for compensation.

Some communities in Sokoto are still skeptical about vaccines. But Tambuwal said they are tackling vaccine non-compliance and hesitancy through a wide range of approaches such as engaging with traditional and religious leaders, and youth groups in communities which show frequent vaccine resistance. She explains that if a Muslim or Christian household rejects a vaccine, a religious leader from that religion is invited to speak and convince them of the benefits of vaccination.

“The biggest challenge is non-compliance,” Tambuwal said. “Some community members and caregivers have their own misconceptions about the vaccination no matter the kind of explanation you give them. Sometimes we use religious leaders to be part of the vaccination team.”

Tambuwal said they usually come up with a long list of people and communities who have been non compliant during every vaccination campaign.

“We found a high number of resistant family members who refused our vaccination adamantly and we can’t punish them because there is no law for compulsory vaccination,” she said.

The September polio vaccination campaign in the state was launched at the residence of a high-ranking traditional ruler who commands respect and a large following among locals in the area. There are high cases of non-compliance and a high number of zero-dose children who have never been reached by routine immunisation services in the community.

Tambuwal said it was a “well-coordinated and thought-out plan” because it’s a centre for the community to “gather and hear their traditional leader speak to them.”

Tambuwal added it was also an opportunity for the people in the area of non-compliance to hear the messages and cooperate with them to carry out our vaccination exercise without any problems.

“We wanted to get their buy-ins and make them (locals) our ambassadors so they can spread the message after we have left the area,” she said.

During the vaccination drives, Abubakar and her team move around with biscuits, candies and chocolates to give to children who receive the vaccine. She said this helps to reduce non-compliance by attracting children and pacifying their parents or guardians to allow for the vaccination to take place.

PARTNERSHIPS TO TACKLE POLIO

International partners and donor organisations work with governments and local nonprofits across Nigeria to tackle the polio virus in regions with recorded cases. For many years, UNICEF, WHO, Rotary International and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have been leading these partnerships in local communities.

Tambuwal attributes the success recorded in the fight against the circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus in the state to partners who are “supporting us in all areas.”

“In respect to polio programming, we focus on advocacy, communication, and social mobilisation,” said Michael Juma, UNICEF’s chief of field office in charge of Sokoto, Kebbi and Zamfara states. “We do this while the government takes the lead role in terms of coordination, leadership and also provision of security at the open level, particularly in conflict areas.”

Juma said they engage traditional leaders, and religious leaders, with a view to “sensitising the community to bring children forward, particularly the zero-dose children and ensure that every single child is vaccinated.”

“We also focus on supply chain management for procurement and distribution of vaccines, particularly for routine immunisation and polio, inclusive of the cold chain management, and this slightly has supported us in increasing vaccination coverage, but also reducing vaccine hesitancy,” he said.

UNICEF also works with polio survivor groups in Sokoto through community mobilisation and football tournaments. Juma said there are 217 polio survivors in the area, noting that “sharing true experiences helps inspire other community members and ensure that women and men bring their children for vaccination.”

On Sept. 26, a football tournament was organised for polio survivors in the state as part of activities to mark World Polio Day on Oct. 24, 2024. More than 100 survivors attended, joined by dozens of community members and local partners who came to witness the event.

Abubakar says she is motivated by her work as a vaccinator because she doesn’t want to lose any child in her community. At the end of each vaccination drive, she and other vaccinators attend a review meeting at 4 p.m. to assess progress and challenges such as no-compliance cases recorded during field trips.

Vaccinators and community volunteers who participated in the outbreak polio response vaccination drives received some financial incentives from UNICEF. Juma said each volunteer and polio survivor receives N20,000 ($13) while supervisors are paid N30,000 ($19). Each vaccination drive lasts between two to four days, plus a final day set aside for catch-up for areas that were missed during the immunisation drives.

Despite the progress made in tackling the new strain of the virus and reaching inaccessible communities with the REST strategy, Sokoto state was included in the Axis of Intractable Transmission (AIT) of the poliovirus alongside Zamfara, Kebbi and Katsina. The AIT states are areas where the virus continues to circulate consistently.

“We are hopeful and optimistic to be delisted from the group by December,” Tambuwal said.

“With all the ongoing efforts and consistency, we shall see the light of the day and achieve a

polio-free status.”

This reporting is supported by the United Nations Foundation Polio Press Fellowship.