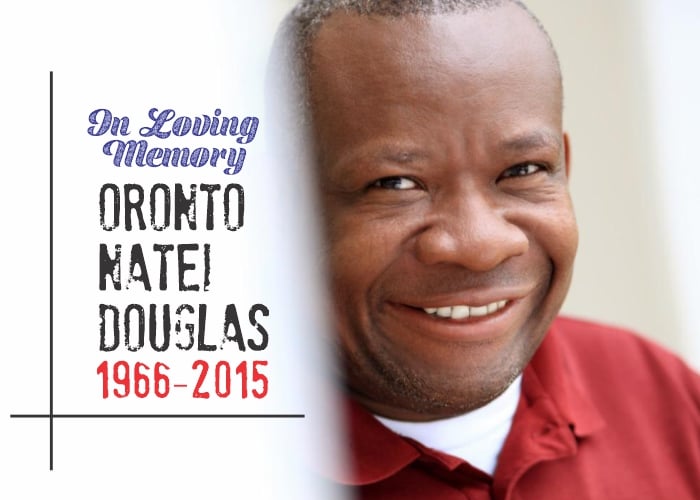

Oronto Natei Douglas, environmentalist and Niger Delta advocate, died 10 years ago after a long battle with cancer. To mark a decade of his passing, TheCable reproduces the transcript of his engagement Interviewed by with Harry Kreisler on May 4, 2001, in which the former special assistant to ex-President Goodluck Jonathan spoke on a wide range of issues on the environment in the ‘Conversations with History’ series at the Institute of International Studies, Berkeley, United States.

Oronto, welcome to Berkeley.

Thank you very much.

Where were you born and raised?

Advertisement

I was born and raised in a village called Okoroba, in the central axis of the Niger Delta, south from Niger in West Africa.

And what year was that?

This was 1966.

Advertisement

Tell us a little about that area.

The region where I come from, the Niger Delta, is a very beautiful place. It is, of course, a tropical belt, rain forest, mango forest, wetlands. A beautiful, really beautiful place – cascading streams, lots of wildlife – the kind of things that make life tick in terms of the unity between nature, humanity, and the totality of the environment. It’s a beautiful place. I urge you to visit.

It sounds quite appealing. Were your growing-up years spent a lot in that environment? Did you go fishing with your father?

Yes, my father is a fisherman and he taught me how to fish. Our house is by the bank of the Niger river. Growing up, it was natural that the first thing you learn to do is to be able to swim and be able to fish because that is our lifestyle, we fish and farm. I enjoyed doing that. I grew up in that kind of an environment before moving off to another part of the country.

Advertisement

You were born to the Ijaw people. Tell us a little about that group.

I am from the Ijaw ethnic nationality, a very ancient ethnic nationality. It is believed by historians to be perhaps one of the oldest nations to inhabit that part of the world. The Ijaws are fishermen, mostly, and farmers. they have been able to conquer the seas by being close to the seas. They go out in waves underwater. So, the Ijaws are essentially fishermen and farmers, and we are very agrarian and rural in our living styles.

How do you think this environment shaped your character and the choices that you later made in your life?

When I was born and when I was growing up, I came to realize the harmony [of nature] and that growing up in that section [of the country] had an impact on me. I grew up not seeing gas flares, at least immediately around me. I noticed the fact that you can just walk to the bank of the river and get fish if you want, for your mother to be able to cook the next meal.

Advertisement

You don’t have to travel four or five hours. You can go into the forest and be able to observe monkeys frolicking in the wild. You could see crocodiles just by the river because the local people, the Ijaw people, don’t kill crocodiles. They don’t kill certain [other] types of animals as well, because they believe that they are deities, they are part of us. Living in that kind of environment, going into the southwestern part of Nigeria, Abeokuta in Ogun state, and returning back to the Delta for my university education, I realized that conditions are no longer what they were. the river had been polluted, the forest desecrated. There had been an assault on the totality of the ecology where I came from. I felt there was a need to stop that, to return back to our pristine [environment], to that tropical [paradise] that it used to be. So, it really shaped one to be able to move beyond what I am seeing today.

Before we talk about what happened to that area, which is a key part of your story, let’s talk a little about your parents. How did they shape your character, do you think?

Advertisement

My father happens to be a fisherman. He is not one who wanted everything, he just wanted to live, he wanted us to go to school, he wanted us to love the environment where we come from, our culture, our tradition. My mom, on the other hand, was a traditional midwife, helping to deliver babies and children. She was one person who everybody knows. She was very active politically, at least in community politics and in the wider regional politics. So, I grew up in that kind of setting, where your parents shape your perspective on life, in terms of nature, your upbringing, and so on. [I was influenced by them] before leaving to go and live with my uncle in Abeokuta, in southwestern Nigeria. He was a soldier.

And along the way, presumably, you were getting educated in schools, and ultimately, a law degree. Any mentors in the course of your education who also shaped your way of thinking about the world?

Advertisement

Yes. When I was at the university, we read a lot about lawyers, like Gani Fawehinmi in Nigeria, Olisa Agbakoba, also in Nigeria; I read about Nelson Mandela, another lawyer who was involved in political activism in South Africa; and other lawyers in other parts of the world, who are taking on the issues that concern the forward march of humanity. And this helped, to be able to say, “Look, I am one that’s not alone. there are people who are out there, who are concerned about changes.” And there is a way to bring a new perspective, perhaps, standing on a different platform.

You know, rather than just human rights, political life, they all dovetail. But I felt that the survival question was important here, the environment upon which we are living, our day-to-day lifestyle, in terms of what we eat, where we go to, what are the other components of our life, the animals, the plants, the trees. These are also very important. And I felt I can also make a contribution along those lines.

Advertisement

You talked about going away and coming back. And the key here is that, in the sixties, the oil companies, especially Shell Oil, came to this area. Let’s talk a little about that. Because on the one hand, you have this rural, agrarian, pristine setting, but on the other hand, there were a lot of resources under the ground that different corporations wanted. Tell us about that, the oil capacity there, and what the consequences were.

Yes. I started getting a feeling that things were not the same when my uncle, who I was living with in Abeokuta, and who regularly traveled home, came back to report to us…

And how far away was that?

I think it’s about 600 kilometers.

You would be how old at this time?

I was in high school then. my uncle came back and was telling us about what was going on at home, that things were no longer the way I used to know, and that when I go back, it is possible that I will not recognize the community, because I left while I was young, shortly after primary school. And he warned me about this. But what I saw when I came back was more dramatic than I could imagine.

This would have been what year?

We are talking here about 1986-87. When I came back, Shell was everywhere. They had taken over the land. They had established kingdoms in all the areas that they operate in. Chevron, as well. Mobil. Exxon. Texaco. Conoco. All the big oil companies, you name them, they have taken possession of our land. And for Shell, Shell came to the Delta in 1937, and after a few explorations had to leave. They returned after the second World War, and they struck oil in a community not too far from mine, called Oloibiri, in 1956. That was the beginning.

They did the thunderous explosion of the boils of planet earth. The exploration activities of Shell led to the realization that underneath was the black gold. And that community of Oloibiri, not too far away from my village, became a rallying point for the extraction of fossil fuel in my community, in the region where I come from. The impact of that first strike was dramatic. There was a huge spill, which according to the old men and women who witnessed that spill, leveled every plant, every animal, took over the whole survival intricacies and mechanisms of nature, and rendered life impossible for months. And it took time. They never had clean-up mechanisms at that time. This was in the fifties, about 1956. And the oil companies continued the attack on nature. Constant spillage and pollution and explosions between 1956 through the nineties. And they still continue now. A few days ago, there was a major explosion in Ogoni, where a lot of oil from Shell, this time again, was spewed into the surrounding environment. The impact is largely on the local people. We are a largely agrarian community. We do not have the industries like the American or the European world depend on. We depend on land; we are from the ground. We plant our crops, we’ve been going to the river to fish and so we depend on nature largely. And when oil is now used as a mechanism to deny us our survival strategies, it is absolutely unjust. And that is what is going on in Niger Delta today.

Let’s explain this for an American audience. Here, in this country, we’re aware of gas stations everywhere. The very companies that you name, they are gas stations everywhere. Here, we’re using the fuel to run our cars, or run our way of life. There’s some pollution associated with that. But you’re at the other end, at the area where the fuel is being extracted from the land, and what you’re suggesting is that it was done in a very uncaring, unthoughtful way. What I want to know is, why did that happen that way? Was the government of Nigeria not protecting the interests of the people there?

I think that we can attribute that to three things. The first is that the oil companies came there with a colonial attitude. We were under British colonialism, and Shell came during that time. At that time, we had no voice. That attitude has not changed. Shell and the other oil companies still feel very strongly that they have a right to our land, and they collaborate with the government.

The second reason is that the government of Nigeria that took over from the colonial government has also not changed their attitude. they felt that they are now the inheritors of colonial power, and they are ruling, governing Nigeria like imperial powers. So this has led us to come to the conclusion that we now have internal colonialists, who collaborate with the oil industry to frustrate our aspiration for freedom, for justice, and for environmental protection.

The third attitude is an attitude of consumers around the world. People are not asking questions about where this oil is coming from. Because the oil that is coming to the united states – and 40 percent of Nigeria’s oil is taken to the united states – that oil is actually tainted, it is bloodied, because in the extraction of the oil, people are killed; human beings are killed; villages are burned down; people, environmentalists are hanged; human rights activists are jailed or arrested or harassed.

In the extraction of oil, what we hold so dear, our culture, our tradition, is desecrated, is destroyed. It is subjected to the most vile of actions. We feel that if people, the consumers who are buying this oil, don’t ask questions, then they are also encouraging the attack on the local communities.

You’re now a lawyer. You’ve come back; you see all that you just described. You start off as a lawyer, and one of your first cases is to be part of the team that defends Ken Saro-Wiwa. Tell us a little about him, what he stood for, and what happened to him.

I was actually a junior counsel in that case. I was called into the case by the senior counsel, who felt that I would be useful because I was from the area, and I knew Ken from 1989, while I was a student union leader. I had gone to see him in his office to profile him on what he’s been doing.

He was a writer and playwright. a writer, a playwright, an activist, an environmentalist, a public commentator, a businessman. I met him. He told us that his vision is for the younger ones to be able not to go through what he and the elders are going through, and that he is currently trying to design a program that will help to bring change. a year later, he started up the movement for the survival of the Ogoni People – that was in 1990 – essentially aimed at mobilizing the Ogoni people. The Ogoni people are 500,000 people, a very small ethnic minority in the Niger Delta, who over the years have been marginalized, like all other ethnic nationalities in the region. the Ijaws, the Ogoni, the Isokos, the Urhobos, and all the other ethnic nationalities have been subjected to all sorts of discrimination and the exploitation of the land. Ken Saro-Wiwa decided to change all that, first starting with the Ogoni people.

But, unfortunately, the government, the military dictatorship at that time, in collaboration with the oil industry, decided that he has to be stopped before he goes beyond Ogoni. And there was a kangaroo court set up. He was brought before that kangaroo military court…

And charged with?

Charged with murder. A very fake charge, a charge that cannot be sustained in any court, any court that is manned by persons of justice. He was charged, and we had to go there to defend him. Unfortunately, the military dictatorship had made up its mind, the oil company was convinced that the best way to resolve the Ogoni issue was to stop the leadership. So Saro-Wiwa, along with eight others, was hanged on the 10th of November, 1995.

How did that verdict affect you and your movement?

It actually triggered us into taking in cognizance that the struggle is not over. That, in fact, it is just beginning. It fired a lot of us, who believe that we’ve got to do much more than we are doing now. We’ve got to internalize the issue. We have got to reach out to people of conscience around the world. We have got to organize. We have got to mobilize. We have got to act in a way so that generations yet unborn do not have to come out and face what we are facing now. So it was a major trigger that helped us to realize that the battle for environment protection, social justice, equity, and peaceful coexistence around the world, especially in our community in relationship with others, is a major work, and we’ve got to move on.

Is it fair to say you’re more of an activist and less of a lawyer now, or do you remain both?

I will say I am more of an environmental rights activist. once in a while I do go to court; very serious cases of political significance, the type that probably the ordinary lawyer may not want to take on because of the danger. Nigeria is still like a totalitarian state. that’s why its advertisement of a democracy… for example, on the 20th of November, the current democratic government of Olusegun Obasanjo ordered 4,000 troops to a community called Odi in the central axis of the Niger Delta, and a community populated by over 60,000 people was brought down.

And why was that?

They claimed that some youth killed some policemen. In civilized society, if you commit a crime, you go out, fish out those youth, and send them to court and have them punished for crimes that they have committed. But in the Niger Delta, because oil is involved and because there is a pathological hit rate for the people, the strategy that was used was to teach these people a lesson: “Let’s wipe out that community.” So they bombarded all the community, and over 2,000 people got killed.

Help us understand the broader implications of the presence of the oil company. We talked about the degradation of the environment, but an additional problem is that because sufficient resources or a just amount of resources are not being returned to the community, there is a greater social dislocation – a lot of crime, a social chaos that leads to a lot of youth violence, and so on. Talk a little bit about that degradation of the human community, as opposed to the environmental setting.

Yes, the human resources. No nation, no people that really wants to make progress will disregard the protection of the human beings in their particular environmental setting. We believe, in the organization that we cofounded [the environmental rights action Group], that [within] the environment, the human person is central to existence. We believe that human beings should decide the fate of the environment. Now, in the Niger Delta where I come from, there has not been an attempt to protect the human person in that part of the world. the oil companies and the government are conspiratorially in this. they attempt to prevent the human being from standing, from moving forward. So what has happened over the years is that because the region is rich, because the people are poor, they are a minority. the elite, who likely hold the country in their pockets, in collaboration with the oil industry, think that they can do anything and get away with it. This had led to the degradation of the environment, and the impoverishment of the human person. Impoverishment, in the sense that the mental capacity, the physical capacity of the people to stand and be in a position to protect what they have is now gradually waning.

Now, the result of all this is that there is a desperate attempt to fight for survival, either individually or communally or ethnic-wide. Individually, you will find that the struggle for the individual to survive has taken a different dimension. Either the individual wanted to go to the oil company to bid for contract, or wanted to depend on an already ravished environment, in terms of doing all the paddling on the river, looking for fish and not getting fish, or going to their farm to plant crops and the crops will not grow, they are stunted. or the fact that the combination of these polluting activities are affecting the health of the human beings there, and they’re dying from all sorts of diseases.

So the problem for an environmental activist, like you, trained in the law, and for the groups that you are a part of, is to elevate people’s consciousness, so that their response, that is, their survival mechanisms, are brought to a plane that takes into account the interests of others, so that it’s not through personal violence or personal corruption, or the pitting of one community against another.

Certainly not.

As this began to happen to these communities, in essence, they were either passive in the face of this overwhelming power of these outside forces, or they turned inward, as you’re suggesting. So what became your strategy? What it is you have to do, now reaching out to your own people, to explain these issues to them?

There has been one major attempt at raising consciousness through violence, that is, revolutionary strategy. Isaac Boro, who was a revolutionary, in 1996 took up arms with about twelve other people and decided that he was declaring a Niger Delta republic.

Of course, that attempt lasted only twelve days. And then, of course, the attempt by Ken Saro-Wiwa, using the environment and the nationality of Ogoni and human rights to provide another platform to mobilize the people, became also another vista for our forward march towards achieving our objective as a people. You must realize that in the Niger Delta, people have been on a long, long road towards freedom. right from the days before colonialism, in fact, before then, there was an attempt by outsiders to take the resources from the people.

Before, it was palm oil. Palm oil was very central in the economy of europe and other parts of the world, and the Niger Delta was a central area where these resources could be gotten. And the palm oil companies, like the royal Niger company, that became interested in these oil resources, used violence to take these oil resources forcefully to Europe. and the people resisted. Their resistance, of course, was crushed with superior firepower.

We have seen all these phases of attempts to change the situation. We feel that our strategy should continue to be that which will ennoble humanity, using peaceful, non-violent strategy to mobilize our people, to raise consciousness, to organize at the village level or even at the hamlet level, town level, city level, family level.

First, to convince ourselves and inform ourselves that, “Look, the situation we are in now can be reversed, and we have the capacity to do it if we are organized.” It is only when we organize that we can achieve victory that we so aspire to. And so the organization of these various processes is on.

But as you must have read and have noticed, it rises up once in a while, and goes down again, and because the oppressive mechanism that has been put in place at every point in time suppresses them, and because the people have designed strategies which are peaceful, which are ennobling, which the oil companies and the oppressive internal colonialist finds very abhorrent, and they push down to crush those [people.] or we continue to remain hopeful that the rest of the world will wake up one day and say, “Look, there’s injustice here. Let us move in there and help this poor, voiceless, defenseless people.”

Let’s talk about that because, clearly, in an age of globalization – on the one hand, you have these companies moving all over the world, extracting resources here, whatever the consequences, selling the product elsewhere – but there is a kind of an international civil society, I guess we could say. And in that realm, ideas are important. Nongovernmental organizations are important. What are the strategies for calling the attention of this international civil society to this particular predicament? What then becomes important? The media? What else?

First of all, we discovered that what we were going through in the niger Delta was not unique to us. I have been in the states now for two years, and I have had the privilege, or misfortune, of visiting communities that oil companies, big industries, target their polluting activities on. I have visited “cancer alley,” Richmond …

Here in California.

In California, Richmond, here in California and then up there in Louisiana. That whole belt from new Orleans, right down to Baton Rouge, and Aspen, Diamond, Nocco, and all those areas. You will find that pollution has been targeted on these people. and they’re usually poor, voiceless, and defenseless.

They are also in the minority. We are not alone, we realized. and because we are not alone, we also realize there are people who are privileged by virtue of the fact that they have not been in these pollutant communities, but they have a conscience, they can speak out and stand for justice.

So we are making attempts at making linkages with these communities and human rights groups, local community groups, platforms, universities, social groups, and so on. These connections have been made with a view to building a common consensus, so that we can globalize our existence against injustice and oppression, whether in California or in the larger united states, whether in the Niger Delta or in the larger Nigeria and Africa, that we can build consensus to stop these injustices.

The movement is on, and I’m very happy to say that we are making progress.

There’s an irony here, that the perception of the injustice, of the awful things that happened, occur in the local area. It’s your knowledge of your own community that is the first step in understanding what’s happened. But in a way, you’re suggesting that ultimately, effective action comes when all these communities whose environment has been degraded, where the human resources have been injured, it’s only by linking them up in a communication network that traverses the globe, that you might get a political response.

That is what we are saying. the united states and its people have a central role to play in the resolution of the polluting nightmare that humanity is being presented with, and which we face today. the good news is that within the United States there are good people, there are people of conscience.

There are people who are willing to stand up and say no. We read beautiful things about what happened in Seattle, when the youth of the united states stood up to say “We are saying no to Wto.” and then, of course, I was involved in the protest against the World Bank a few years later, in 2000 April.

And there, too, we noticed a large sentiment of youth from the united states and other parts of the world, saying no to the IMF, saying no to the World Bank and their policies against people who are poor, who are voiceless, who are defenseless. And this concordance of youth, this concordance of people of conscience, this concordance of communities that are affected, will lead to a global union that will say, “We are tired of pollution. We are tired of environmental degradation. We are tired of policies that will affect humanity. We are tired of policies that do not ennoble humanity and provide an opportunity for humanity to reinvent itself for the years ahead.” We are too short-term in our approach to the survival question and to the future of human progress.

Now, concretely, once this consciousness develops, what form do you think change will take? Will you see a situation where there is a learning process within the oil companies, so they will change their programs and their policies, so that the extraction of the oil does not have the consequences that it does?

Yes, I hope so. But I am very worried that their concern for profit is too preeminent. That hope could be lost because of their concern for power, their concern to grab whatever they can lay their hands on, provided it can produce dollars.

These are concerns that may pitch them against the people, and eventually there could be a collision. If that collision happens, people power versus corporate power, if that collision happens, I can imagine the consequences, which could be manifested in various forms. over the years, corporations have become adept at capturing power at governmental level, sponsoring people in places of power.

You mean at the national level.

At the national level, yes, whether in Nigeria or, I’m sure, in the united states and other parts of the world, where they have designed programs of influence, to become leaders in the various communities where they are, so that they can have a strong hold on policy, on decision-making processes, and, in fact, in the general method and way of life of the people of that particular nation or locality.

They might, over time, initiate programs to co-opt and de-fang the opposition?

they have a capacity of metamorphosis. they are like chameleons. The will change course where the profit is. We are saying now that the oil industry is not sustainable. We are saying that the way and manner it is being carried out does not take into cognizance our future.

Now, when the voice of reason prevails, when ideas for the protection of the environment and human rights become holistic, I think that the oil companies will be on the defensive if they know they cannot win. and if that happens, they will then begin to reinvent themselves. they will begin to search for a new means of becoming relevant. We must be on the lookout, though, that in their present manifestation, that chameleonic manifestation, they must not change to more monstrous apparitions that we may not be able to control.

What about the role of government here? You suggested earlier that the government of Nigeria, after independence, was perceived by you and your people as a colonizer. What do you see as a long-term solution for a place like Nigeria, made up of, I think, 250 different peoples, and in situations where some of them are located in resource-rich areas, on the one hand, but areas where they are tied to the environment and don’t want it destroyed? What does the political future look like for a place like Nigeria?

We believe that discussion, debate, and dialogue are key to the resolution of the issues in the Niger Delta and Nigeria. We have suggested, and the debate is on, that there should be a sovereign national conference where these various ethnic nationalities can come together to discuss their relationship to the state, how we’re going to relate with each other, what kind of federation we want.

Right now, Nigeria is called a federation, but, in reality, it’s a unitary government. The federal authority rules Nigeria with an iron fist. It will not put up with any opposition from any quarters. And so we need to change that; we have to unite. We believe that Nigeria should remain as a country if we can resolve the issues that are being raised by the federated units.

We are saying that we need to protect our culture, we need to protect our way of life, we need to protect the environment, we need to respect human rights, we need to make progress in terms of our aspiration to development. We need to provide clean water, we need to provide electricity, we need to provide food and medicine for the sick, and so on. Government is not interested in all these, and this is where the conflict is coming from. We are saying that that must change.

So we need to discuss, and in discussion, the issues we have raised must be analyzed. We have called [for] and we are demanding resource control. When we talk about resource control, we mean

that we want to be in control of the air that we breathe. We don’t want to breathe polluted air. We want to be in control of the forests and the land, where the wildlife and the rain forest bring forth life. We want to protect the waters. We don’t want those waters polluted; they are our vital resources.

Oil and gas are temporary resources that could evaporate, that could go away over a given period. It is not a key issue, say, over a thousand years. Because we are going to be there for many more years than that! We have been there for more than 10,000, 20,000 years, as human memory can remember, and there is a possibility that we will remain there for more thousands and thousands of years. But oil is very temporary. When it’s finished, it is finished. But the people, the land, the environment, will remain.

The challenge is: what is going to be left to be integrated? An impoverished land that after 2,000 years cannot be healed, or what? these are our legitimate worries. We are calling for resource control by our people.

The same is true in the United States. the people of the United States must call, must demand resource control, in the sense that you must have your right to breathe clean air. You have a fundamental right to clean air. You must have the right to swim in a stream or a river – it is a fundamental right. You must have the right to eat food that is not polluted or poisoned by chemicals. these are resources that you as a people should have control of. right now, it is not in the hands of local people, whether in Nigeria or in the United States. It is in the hands of big government and big corporations. this is what we are for, and this is why we are fighting.

An obstacle to elevating consciousness on these issues that transcends the view of a particular government or, say, the oil companies, is the multiplicity of communal identities. What is the answer? On the one hand, making people realize these universal concerns that you’re articulating about the environment – you want to be able to have clean water wherever you live – but on the other hand, this competition for resources that focus around ethnic identities?

You see, the beauty of having different ethnic nationalities can not be imagined. the various ethnic nationalities in Nigeria present us like a balloon in a rainbow, with beautiful colors as the background and we are floating in the air. We love that. We want nigeria not to be a straight-jacketed, one-ethnic nation. the beauty will be lost. You know, a strong point about nigeria is that you have these various ethnic groups who, maybe not of their own will, have been brought together to live together. And the aspiration of the ordinary Nigerian is to be able to create a nation where every nationality will have a place, will not be threatened, will be protected.

It is true that bringing oil into the equation, especially in the niger Delta, has heightened tensions because of the manipulations the government and oil companies have been able to put in place. Before oil, there may have not have been conflict over where a particular boundary is, even if they are aware.

The true communal conflict resolution strategies, the African way of resolving issues, these matters have always been resolved without unnecessary shedding of blood. But with oil, and with the government, and with guns, and with bullets, and all that being thrown into the equation, with profits having a domineering role in all this, you’ll find that this conflict becomes heightened, and our people are brought together to fight against one another.

Over the past year or two, they are beginning to realize that there is a desire to put them perpetually at war, while their oil is taken away. at the same time, they have realized that when the conflicts are going on, the oil never stops flowing, it keeps on flowing. So they realize this, and they are beginning to rethink that, “Look, it is not because of anything [between us.] I think it is because of the oil, and so we must stop fighting.”

So the realization is on. the mobilization to bring about this realization has been tough, has been intense, it has been quite nerve-wracking, but I think we are getting there. It’s a gradual process, and we will get there.

Your story, the journey of your life, is an interesting one. Reflecting on your own life, what does it take, what are the requirements, what is the job description for what you do? It strikes me that starting as a lawyer, it’s clear to see what it takes to do that work. But you’ve moved to a more important platform. What are the inner strengths and where do they come from in your particular case?

I am motivated, essentially, by the fact that every human being ought to make a contribution towards human progress. We are not just on this planet to eat, to sleep, and then we die. I think we came because we have a contribution to make.

My little contribution in the area of environmental human rights is to further the whole debate about our progress. now, moving from active lawyering, if you like, into active environmental human rights activism, I don’t see it as a movement away. they are all part and parcel of the same circle. It is absolutely important for us to understand that the dynamics of change could come from any quarter, whether through law, through lecturing, through activism, but they all come together.

It could bring a lot of pain – for example, you have been arrested for campaigning on the environment; you are being hanged, or you have had to go for months and years having to own more than one passport, for example so that you can be able to sneak out of a dictatorial setting as we had in Nigeria.

Activism comes with a lot of pain, a lot of frustration, a lot of discomfort. But I think that at the end of the day, you will realize that progress has been made.

If students want to do this kind of work, how would you advise them to prepare for their future?

I think the first thing is to know about the environment in which they live. for example, the University of California at Berkeley, the surrounding environment, what is there that is not preventing the air from being wonderful? What is it that could poison the waters? at the same time, what could create harmony between one student and another? I’m talking about human relationships. I’m talking about the surrounding trees, the environment, the buildings, and so on. that is the first place to start. start with where you are, and begin to fight, to demand justice where you are. then when you go to the larger society, it becomes a wider platform – the audience, the participants, your neighbors, the government and so on – where you face the issues. So there is a need for a preparatory stage.

Some people may not be involved in these processes in the university, but when they go out of the university they could become engaged. for example, if everything is harmonious here at the university, there will be nothing for you to fight to protect because it’s already protected.

But when you go out, you could find a situation where waters have been polluted, the air has been poisoned, and people are dying because of pollution activities by industry that may just be somewhere close by. And sometimes, they may not be so close to you. Like the arctic region of the united states, in Alaska, for example, there is a major campaign to stop oil companies from going into the arctic Wildlife refuge.

I support the position that the oil companies should not go there, because if they go, and if they do exactly what they are doing in my own country, flaring gas, polluting the land, and the ice melts, the impact of the melting of the ice as a result of global warming could have effect in the Niger Delta, where if the sea level rises as a result of the activities there, and there’s an example where we will be affected, we will be wiped out. The connections between what is happening here and what is happening in my country are so glaring.

A student leaving the university, or if that student is at university now, he or she should realize that there are activities that could impact him or her whether they are in the university or outside the university. If the climate becomes warmer than this, or things become so bad, then it does not matter where the student is hiding, he or she will be affected.

In listening to your story and your journey, I’m struck by what internationalism really means. On the one hand, it means a respect and understanding of different peoples and their cultures, to know the Ijaw people and what happened to them, and so on, with regard to the change in their environment. But on the other hand, a real sense of internationalism as interconnected, and that what’s happening to the environment in the Delta region is not unrelated to what’s happening to the environment in Louisiana or in Richmond, California.

Yes, there is no difference. The linkage is clear. We all live in one planet, planet earth. there is an attempt to create another living space somewhere in space.

The first tourist went to space just the other day, and maybe in the next ten, twenty years, a lot of people may decide to go and stay in space. But if humanity does not protect planet earth, and he or she thinks they will escape to space to escape from the pollution tendency here, then I think that we will just be going around in circles. Because when you get there, the same lifestyle, the same kind of activities, that same part of the universe that people are trying to escape to in the next thirty, one hundred years will become polluted, you know.

It’s like a “not in my backyard” kind of situation: we can pollute the Niger Delta, but don’t pollute the united states. and right now, it’s becoming clear that they are also polluting the United States in communities of color, African American communities, and so on and so forth, in communities where people do not have political voice. So the connections are very, very important. We must make linkages, because the culprits are one and the same, those that are interested in profit and in power. they are united, they are organized in polluting, in taking away these resources for themselves and not for everyone. these are the challenges that we face.

One final question, requiring a short answer. I’m struck by your perceiving what had changed in your early life, by knowing what you had had before the oil companies came. It sounds to me like that’s also important. That is, to build on multiple identities, to compare one perception with another, to actually see what’s wrong with the present situation and try to change it.

Definitely. that is a major part in achieving our common goals, seeing the connections, identifying your life with the lives of others, and seeing the relationships that affect our common objectives.

With that note, Oronto, I want to thank you very much for taking the time to be with us and talk to us about the evolution of your thinking and the course of your life’s work. Thank you very much.

Yes, thank you very much.

© Regents of the University of California