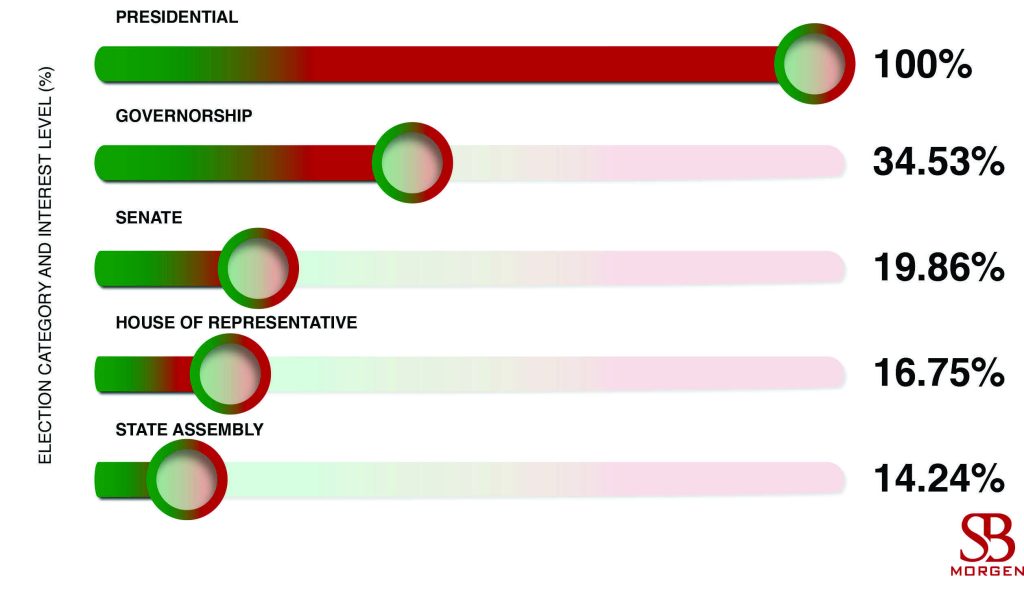

It’s sad but unsurprising that the EiE-SBM Intelligence report from last week, which forecasted the possible outcome of this weekend’s elections, identified the declining interest in down-ballot elections among the Nigerian population. When we were in the field, ALL respondents we met, and we met 11,534 of them, had something to say about the presidential election. Sadly, only about a third, 3983 of the 11,534, were interested in the governorship races in their respective states. Interest in the legislative races was even more pathetic, with only 2291, 1932 and 1642 people having an opinion about their Senate, House of Representatives, and State House of Assembly races, respectively.

To understand why this is so, we have to look at what Nigerians expect from their legislators, and this story from Delta State might help.

Last December, the Minority Leader of the House of Representatives, Ndudi Elumelu, was on a ward-to-ward campaign train for the Peoples Democratic Party in Delta North Senatorial District with the senatorial candidate of the party, Ned Nwoko. They went to Oko on the banks of the River Niger, and they were accosted by angry youths who accused Elumelu of failing to bring development to the area. As a result, these young people stopped him from entering the community. Hours were spent on placating the youths, and in the end, promises of local development were made to bring better roads, electricity, and social amenities to the locality. Ndudi Elumelu was actually asked to go swear an oath at the local shrine to show his sincerity. The senatorial candidate, Ned Nwoko, a Muslim, promised that he would work on the local flooding problems and get roads done from Oko to Ndokwa East through Isoko to Warri.

The individuals involved are a sitting legislator and an aspiring candidate, but their constituents were not asking them to make great laws for the country or the Anioma region or even the state of Delta. No, the people were making construction requests that ought to be directed at the state and local governments. So as far as that community is concerned, those targets would be what a legislator ends up getting judged for.

Advertisement

This is a part of the problem. Nigerians are demanding material outcomes from positions designed to deliver abstract outcomes, and we do not know the difference.

In the eyes of Nigeria’s voting market, how valuable are laws?

How much do a hundred laws weigh when placed on a scale?

Advertisement

How much can a thousand laws be sold for?

The first question is easy to answer favourably, but the next two demand answers that require that an abstraction like Law be treated like a material substance and probably not seen as valuable if a quick, simple answer is not provided.

A difficulty with abstractions is common in societies with low literacy rates, and Nigeria has a 62% literacy rate. Simply put, 38% of Nigeria’s purported 200 million people, or more than 76 million human beings, cannot read and write. An adult literacy rate is the percentage of people aged 15, and above who can read and write with an understanding, a short, simple statement about their everyday life, and even most people who could pass as literate by this standard are still likely to struggle with the concept of a legislature.

This pressure is why the National Assembly got the administration of President Olusegun Obasanjo to approve the Constituency Development Project programme that would allow legislators to pick development projects for their constituencies, which has become the primary criteria they are judged by locally. These constituency projects are sited in the constituencies of Senators and Representatives by various ministries, departments, and agencies of the government as appropriated in the budgets of the Federal or State governments and have Billboards identifying the legislators responsible for influencing their siting.

Advertisement

The successful conceptualisation and practice of Western-style democracy owes a lot to the work of Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, an 18th-century French social and political philosopher whose work in political theory and jurisprudence gave rise to the term “Trias Politica” which translates in English to “Separation of Powers” and laid the skeleton for the political model that shares political authority into separate legislative, executive and judicial bodies that complement and check each other. The predominant model in most of the world before then was the monarchial model that typically had all three powers vested in an individual with the attendant problems with fairness, competence, and oppressive tendencies that are commonplace with absolute power.

Nigerians are very reluctant to accept the separation of powers and responsibility and keep asking that members of the National Assembly deliver in ways associated with the Executive and the legislators have responded to the market even though this has made them vulnerable to the control of the Executive.

On 30 May, Nigeria will have 109 senators and 360 members of the House of Representatives, but most Nigerians do not have a legislative agenda for their legislators at the state and federal tiers of government. It will take a while before Nigeria can get legislative excellence because the voting market simply doesn’t reward it.

Nwanze is a partner at SBM Intelligence.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.