The mood in Dapchi is still sombre. Most families are gathered in congregational prayers under Neem trees at street corners, while military checkpoints, which where hitherto absent, are now glaring at strategic places. This town, in Bursari local government area of Yobe state, north-east, Nigeria, is yet to recover from the attack on the Government Girls Science and Technical College on Monday, February 19, 2018.

Suspected Boko Haram insurgents, masquerading as soldiers, lured 110 girls into their vehicles, abducting them. Now, it is no longer the abduction that matters. But the reality that even after ten days, nothing significant has been heard about the rescue of the girls. While the Nigerian army and police are trading blame on who should have been responsible for the security of the girls, their parents are still waiting, in excruciating longing, for their return.

Hajia Ibrahim M-grah, 45, has not had any meaningful sleep for almost ten days now. Her troubled mind has been conjuring up images of where her 17-year-old daughter would be. Would she have any food to eat? Would she be asleep now? What are they doing to her now? Would she become a Boko Haram bride and mother? Or will Allah answer her prayers and bring her back soon?

She was seated cross-legged on a blue rubber mat when TheCable met her at a family yard. Despite breastfeeding her infant, the love and joy mothers usually transmit to their suckling babies during such bonding exercise was missing. Rather, her eyes were bleary and puffy with heavy bags of sorrow underlining them.

Advertisement

“I am not myself. I cannot sleep. I am not in my senses now. I am suffering. I am missing my daughter.” This was the little she could say in Hausa through her husband who interpreted.

Her husband, Ibrahim M-grah, 60, says he had bought her sleeping medication but rather than being cured of sleeplessness, she is having frequent heart palpitations. Speaking of their daughter, he says, Fatima Ibrahim M-grah, in SS3 (final class), has only three or four months left to conclude her education in that school.

“She has been in the school since JSS1. There was no problem. But she only has three months left to finish,” he says, raising three fingers up. “After she completes her school, she wants to go and read health tech at the school of health technology, so she can be a community health extension worker.”

Advertisement

Based on the Nigerian academic calendar, she ought to write her final exams — the senior secondary school certificate (SSCE) — in May after which she proceeds to the next level of her studies in September, but who knows if this dream will ever see the light of the day.

Fatima is not M-grah’s only daughter that was missing, but he prefers to talk about only one.

“I have two daughters in that school. The second one, Hafsa, is from my second wife (I have three wives), but let’s not talk about that,” he says, trying to suppress his emotions.

Fatima — baby of the family

Born on June 30 2003, Fatima Bashir had her whole future, bright and beautiful, before her. Her problem wouldn’t have been lack of money to pursue an education as her father, a civil servant, is ready to sponsor her through nursing school. He wants her to be a nurse and that is why he sent her to a science school.

Advertisement

But on the night of the attack, her sister who is also in the school escaped, unfortunately she couldn’t. The house has been silent since then.

“Since I have not seen my daughter, I am not comfortable. I cannot eat and I cannot sleep,” her father, Bashir Alhaji Manzo, says. He is the chairman of the Association of Parents of Abducted Dapchi Schoolgirls. “I want the government to produce our children with immediate effect,” he says.

Boisterous Fatima

Fatima Mohammed, a 16-year-old SS2 student, is an extraordinary child. Wery gifted and obedient, her father testifies. The elderly man in his sixties is the district head of Jumbam, a small town near Dapchi. He was receiving visitors who came to commiserate with him on the kidnap of his daughter, when TheCable met him.

“I truly love my daughter,” he says, crossing his legs on the mat in his yard. “She is very obedient to me. The love of a father to a child is never expressed that is why I cannot express how much I love Fatima.”

Advertisement

He shakes his head and tries not to blink so that the water gathering in his reddening eye wouldn’t drop.

“I always think about her – when I want to eat, when I want to sleep. I will be thinking which condition will she be in now? Even when I am feeling hungry and they bring the food, I cannot eat again. When I sleep, I will wake up and I cannot sleep again,” he reveals.

Advertisement

Fatima is the sixth child and is described as a very boisterous especially in anything education. She made graffiti on the wall of her mother’s room – telling everything about herself, her prospects and her schooling and friends.

“She used to tell me that when she completes her school, she wants to become a medical doctor to assist the less privileged in the society. I wish the government put more emphasis and try their best to rescue the girls,” he adds.

Advertisement

Zara – grandma’s love

With sunken eyes and a lean, feverish appearance, Hajia Fanankulu, the grandmother of 14-year-old Zara Musa, is sprawled on a purple prayer mat, quietly counting the beads on her tasbah.

“I am begging the government to try their possible best to release the girls. This girl is very precious to me. Her mother lives in Damaturu, but the girl lives with me here. I am taking care of her, and she is helping me, but since this incidence happened, I did not sleep, I did not eat. My chest is paining me, everyday,” she says, coughing and striking her chest.

Advertisement

Living in denial

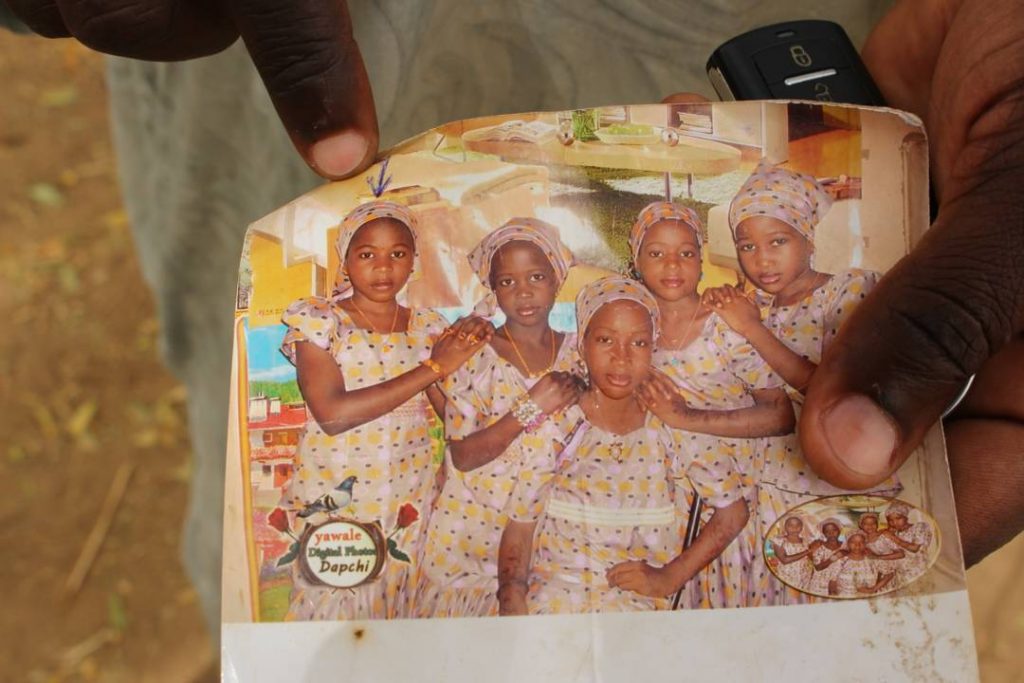

For Fareed Musa (not real name), whose three daughters were all kidnapped, living in denial is the best way to save him from having a mental breakdown right now.

“I cannot begin to talk about it. If I start, I cannot finish it, except you want to see my tears,” he says. Musa wouldn’t reveal his real name, those of his girls, no show any of their pictures. The reason is that he accepts and leaves everything to God.

“What can I begin to say? Is it how I just paid their school fees and carry provision to them in school? We are always together here, and all of a sudden, I cannot see them again? Boko Haram stole my children?”

His eyes reddened a bit, but he threw in a joke and eased into banter with his friends who were hanging out with him on a mat under a Neem tree.

“Sorry journalist, I do not want to talk about them or give their names,” he says, tilting his head apologetically. When asked if the mother of the children would speak, he waved his hands aggressively. “My wife too cannot. She will start crying. If I (the man) cannot, then my wife cannot.”

He however hopes, in his distant mind, that they will return. And if they don’t, “I give praises to Allah,” he says.

1 comments

In the educationally disadvantaged north, Those that pursue education are in danger. How can there be progress!