Pic.5. Some sensitive and non-sensitive election materials returned to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) Local Government office in Suleja, Niger State, following the shift of Saturdays (today) presidential and National Assembly elections to Feb. 23. The governorship and house of assembly, FCT area council elections have also been shifted from March 2 to March 9.

01431/16/2/2019/Jones Bamidele/NAN

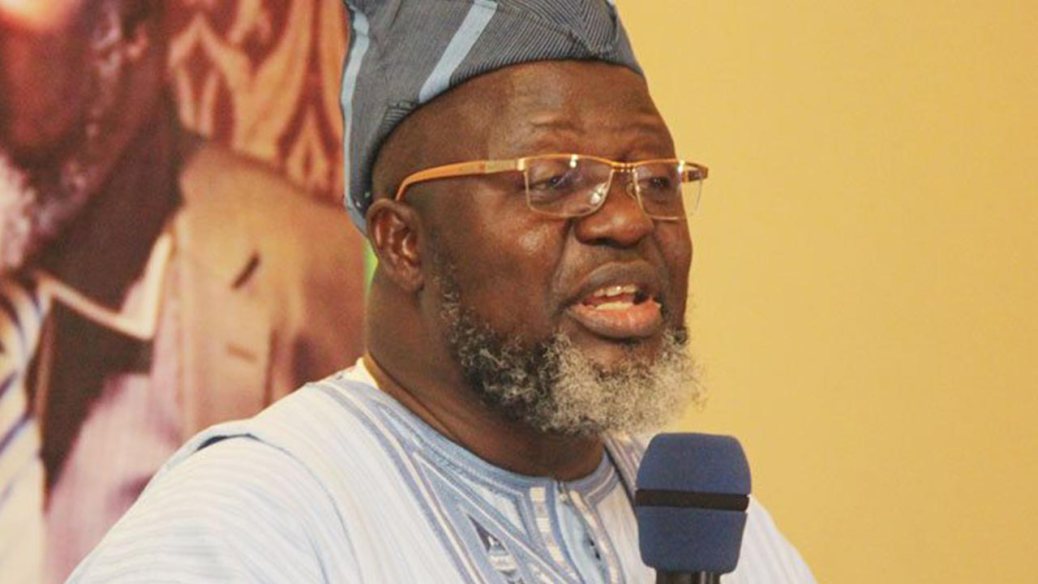

Had everything gone to plan, a new or recycled Nigerian President would have emerged by now. But it wasn’t to be. Roughly five hours to the scheduled commencement of voting on Saturday morning, Mahmood Yakubu, a Professor and Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), announced a one-week postponement, citing sabotage, bad weather and other logistical challenges. But the issues run deeper.

This is the third consecutive general election to be postponed in Nigeria. In 2011, voting was already in progress when INEC halted proceedings, sensing that the inadequacy of ballot papers could derail the integrity of the vote. In 2015, the country’s highest security officials — and it is widely believed they had the backing of former President Goodluck Jonathan — boxed INEC into a six-week postponement on the claim that they couldn’t guarantee protection during elections unless they were given time to further decimate Boko Haram. But, even if the security chiefs hadn’t forced INEC’s hands, the election would have failed spectacularly — because INEC was not ready

Yakubu’s election game plan lacked flexibility. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear it focused mainly on best-case scenarios, giving little thought to bad-case or no-case scenarios. Suspected incidents of arson led to the destruction of vital electoral materials in three local governments in Nigeria’s South-East and the North-Central, but had there been a plan for last-minute loss of vital materials, the pace of readiness in those places would not have been affected. INEC created five zonal airport hubs to facilitate the delivery of electoral logistics round the country. But it had no fallback options for flight cancellations, which can be triggered at any time by bad weather. Maiduguri and Yola, two of those airport hubs, have been raided by Boko Haram this month, yet there was no backup plan for the worst, such as another raid by the insurgents.

There’s no denying that INEC left far too much in the hands of fate, but the umpire has at times been a victim of desperate political power tussles at the expense of national interests. Adams Oshiomhole, Chairman of the ruling party, President Muhammadu Buhari himself and Senate President Bukola Saraki were all part of events that set INEC back by many months in 2018. First, it was the Executive, for whatever reason, that didn’t include INEC’s supplementary needs into the 2018 budget. Again, after presenting the 2018 budget to the National Assembly in November 2017, the Executive didn’t immediately submit a supplementary budget, waiting a further seven months before finally presenting it in June 2018. By then, tension between the Executive and the Legislature was sky-high due to suspicions Senate President Saraki was about to dump Buhari’s party for the opposition. Saraki failed to consider the supplementary budget for INEC. Instead, he announced his defection from Buhari’s All Progressives Congress (APC) to the opposition Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), and ordered an abrupt and lengthy recess to prevent impeachment by majority members of Buhari’s party. The Senate eventually approved a budget of N189billion for INEC in October, but by November 2018 it was still dilly-dallying over the mode of sourcing payment; that was five months lost from date of budget presentation, and close to a year wasted in all. Crucially, November 2018 was four months to the presidential election; meanwhile, the INEC smart card reader takes six months to make! Incidentally, those at the heart of that atrocious politicking have been some of the most vociferous critics of the election rescheduling.

Advertisement

Despite all these, recent history shows it isn’t all doom and gloom for Nigeria yet. After the 2015 postponement, Attahiru Jega went on to lead INEC to organise an election that saw an opposition candidate defeat an incumbent President for the first time in Nigeria’s democracy. It may not have been perfect but the opposition couldn’t have won if the election wasn’t largely fair. Yakubu can do the same. However, for waiting till the 59th minute of the eleventh hour before announcing the postponement, voter apathy is already brewing. Of the 14.28million voter cards added to the voter bank ahead of this year’s elections, 10.87 million (representing 76.12%) had been collected as of the February 9 deadline. The percentage comparison to the overall 2015 figure shows a decline of 5.86%. This postponement coupled with the non-decentralisation of voting — voters must travel to the original locations where they registered — means INEC can expect a significant downturn in voter turnout on February 23.

When the 2019 elections are done and dusted, Africa’s largest economy must hold “important conversations” about its electoral process, as cited by Yakubu. The budgeting and funding process should be made immune to the whims and caprices of the Legislature or Executive; one law compelling budget presentation and passage within a certain timeframe takes care of that. It’s time for voting to get electronic, consequently decongesting polling booths and removing a major percentage of INEC’s logistic burden. Nigeria’s diaspora makes the sixth largest remittance in the world yet it is sidelined from voting — something well in progress in smaller African countries such as Botswana, Chad, Central African republic and Cape Verde.

But, the most important of all, Nigeria’s election dates need sacrosanctity. Everyone knows that Election Day in the US is the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. By default, the next Election Day is November 3, 2020. It will be so shameful if Nigeria can’t achieve something similar, beginning from 2023.

Advertisement

Soyombo, former Editor of the TheCable and the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), tweets @fisayosoyombo. A variant of this piece was originally published by Al Jazeera.

Add a comment