BY OYEWOLE AKANDE

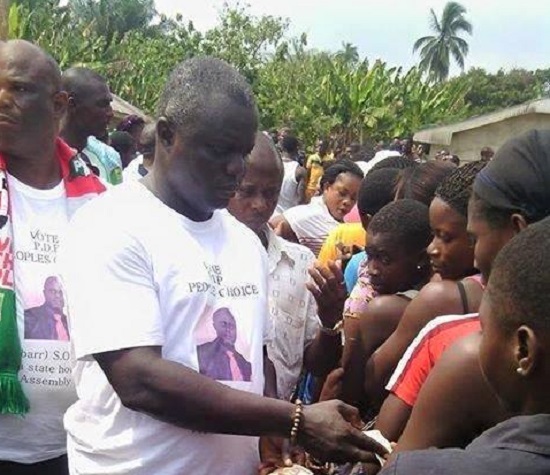

Vote buying is perhaps one of the hottest topics in Nigeria as the 2023 general elections draw near. Many commentators have speculated that it is the driving reason behind the recent currency swap policy by the Central Bank of Nigeria. In recent off-cycle elections in Ekiti and Osun states, there have been credible and reported incidents of high rates of vote buying, with political agents openly inducing voters with monetary rewards to make them cast their vote for their preferred candidate.

The educated elites who dominate the media space have reacted to this development with dismay. Recent headlines include alarming statements calling it a menace, another insinuating that it is a threat to the country’s democracy and yet another call it a danger that must be avoided. The Independent Electoral Commission (INEC) has been so rattled by this phenomenon that it has recommended that the national assembly legislate for a life ban for any politician or political party caught in the act of vote buying.

But is vote buying the menace it has been made out to be? If we consider critically the evidence before us and the historical lessons from other countries in their democratic evolution, we may have to conclude, counterintuitively, that vote buying is in fact a good thing and the evidence that our democratic process is maturing, and that our elections are becoming freer and fairer.

Advertisement

We need to take a step back and reflect on how power has changed hands historically in the communities that make up modern Nigeria. Power change usually occurred through two principal methods. The first method was by the use of raw violence, that is one leader uses force to take over power from another leader or upon death, there was an armed power tussle for succession. The second method was through a process of negotiation, where the handover process was mediated through a small group of people, usually unelected by the majority, deciding who was the next leader, hence why we retain the name “kingmakers” for anyone who plays a similar role in our society today.

The idea of democracy is old, it dates back to Athens in the fifth century BC. However, the idea of universal suffrage – that is the right of all eligible adults to vote in political elections – is a new idea. It is an idea that only got its start in the 19th century in England and even then, the stated objectives of the campaigners only included the fight for universal male suffrage. Women only got the right to vote in the US in 1920 and it took until 2005 for them to be able to vote in Kuwait.

In the West, the struggle for universal suffrage unfolded over decades as the activists had to build popular support for their struggle and they were able to change the mindset of the majority of the people. However, in Africa, universal suffrage was largely imposed without any process of cultural advocacy. At independence, the colonial powers imposed upon indigenous cultures the idea of universal suffrage. It was a noble idea, but it was always bound to provoke resistance from the elites in societies where the gap between the rulers and the ruled had always been vast. How do you get elites who have always imposed their wills on their subjects to now go and beg those same people for their votes?

Advertisement

In Nigeria, after independence, this disconnect has largely meant sham elections more often than not. The tactics may vary, but there are usually three methods through which Nigerian elites had ensured they won elections. The first method was to suppress voters’ turnout through high levels of violence in places where they did not have strong electoral support. The second method was to ensure they inflated the number of votes cast in their strongholds by thumbprinting as many ballots papers as possible. The third method was working with electoral officers in collation centres to change the actual count to more favourable results.

The history of elections in Nigeria has followed this depressing pattern until 2010 when Attahiru Jega was appointed head of INEC. Most Nigerians have failed to notice, but over the last three electoral cycles (2011, 2015 and 2019) and in off-cycle elections, INEC under Jega and his successor Mahmood Yakubu has gradually closed those three loopholes for rigging. The first loophole to go was the ballot stuffing trick with the introduction of biometric systems to verify the identity of voters on election day. This has made it impossible to inflate the numbers of voters beyond those who are verified as present. INEC closed the second loophole by adopting the policy of cancelling elections in areas affected by violence and ordering reruns in those areas with higher levels of security since the available security agencies can be concentrated in these pockets on rerun days. The third loophole has been closed by the new Electoral Act of 2022 that allows for electronic transmission of results, which means there is no longer a manual collation process that can be manipulated easily.

As a rational Nigerian politician, what do you do when you can no longer rig elections? Do you actually start to govern well in the hope that your performance will make you and your party attractive? Well, since you cannot rig the vote, you switch to buying the vote. Game, set, match.

Vote buying has a long and distinguished history in elections. In a fascinating research work by Susan Stokes and other researchers, they present evidence of how rampant it was in the West until recently. It is worth quoting at length from their paper:

Advertisement

“A commission on electoral bribery reported to the House of Commons in 1835 that, in Stafford, $14 were paid per vote cast in a hotly contested election. Polling proceeded over several days, and electors were called to cast their votes in alphabetical order. Those with surnames beginning with A’s and B’s didn’t get much for their votes; but if the polling lasted two days, the names which began with an S or a W were of the greatest value. At Leicester, also in 1835, as soon as the canvass began public houses were opened by each party in the various villages near the borough. The voters were collected as soon as possible, generally locked up until the polling, and according to an election agent, [they were] ‘pretty well corned’

Across the Atlantic Ocean, a party official in Newark, New Jersey, offered the following description of Election Day, 1888: [A] room is secured, generally in the rear of a saloon… At this precinct, there are a half-dozen men located outside with a pocketful of brass checks. . . When a floater comes along, the outside agents simply make a bargain with him. If the price is $2, they simply give him 2 checks…The purchaser sees that the man votes right and tells him to see John Jones in the room at the back of the saloon… The voter has simply to get his check cashed.”

It is striking how similar these accounts are to the stories that came out of Ekiti and Osun states. For there to be widespread vote buying, these four conditions must be met:

- A competitive election where no candidate is sure of victory, notice how in the history above, the value of votes went up as the election progressed in Stafford and the count remained too close to call;

- A large percentage of voters who are not particularly passionate about any of the candidates called “floaters” in the Newark example above;

- Politicians who are willing to spend whatever it takes to get elected since they are confident of recouping their investment handsomely once in office; and

- A way of enforcing compliance by the politicians on election day to ensure that the voter stays bought

These four conditions are going to be present in some of the races in the upcoming general elections and we should expect to hear many more stories of vote buying on election day. As you read those stories, remember it is a sign of progress and evidence that the Nigerian people are beginning to have a say, even if through grubby means, in how their leaders are chosen.

Advertisement

If the research showed that vote buying was rampant in the UK and the US in the last century, how come we no longer hear these stories today? How were these societies able to abolish the practice? Susan Stokes tells us the answer: “What, then, killed vote buying in Britain and the United States? The explanation we offer in this chapter focuses on changes in the electorate, changes that were the effects of industrialization and economic growth“.

In short, as their economies grew, the voters became too expensive to buy. It is easy to buy voters in Nigeria because the “market value” of a vote ranges from ₦2,000 to ₦10,000 (the reported range in the recent off-cycle elections).

Advertisement

This is a significant sum for the average voter in a country with a monthly minimum wage of ₦30,000 yet it is not so high that it is unaffordable to the politician. But what do you do as a politician if the average income rises to ₦300,000?

Therefore, we can see that the solution to vote buying lays in increasing the prosperity of Nigerians. Solutions such as currency swaps and restrictions on cash in circulations are blunt tools that can be circumvented by intelligent minds. The long-lasting solution, proven in other countries, is to make the voters too rich to be brought over.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment