March is Women’s History Month, a time dedicated to recognising the achievements and contributions of women across different fields. What started as a local observance in California in 1978 grew into a national event in the United States by 1987, and today, it is marked globally.

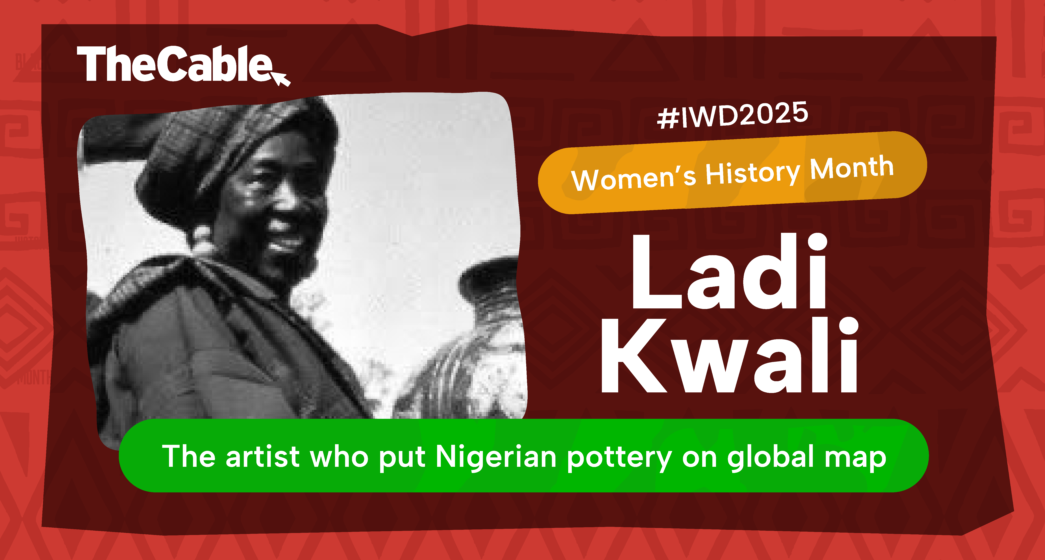

But beyond the well-known names in Western history, countless Nigerian women have shaped the world and their nation in ways that history books often overlook. One of them is Ladi Kwali, a woman whose mastery of clay turned a local tradition into an internationally recognised art form.

She was not a politician or an activist. She did not write books or lead protests. She was a potter, born into a community where working with clay was second nature. Yet, through her craft, she broke barriers, changed perceptions, and left a legacy that still stands today.

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

Advertisement

Ladi Kwali was born around 1925 in Kwali, a small village in what is now the federal capital territory of Nigeria. At the time, Kwali was part of Northern Nigeria, a region steeped in traditions that had survived for centuries. Among the Gwari (or Gbagyi) people, pottery-making was a skill passed down through generations, and women were its custodians.

Unlike modern ceramics, Gwari pottery was made entirely by hand, without a potter’s wheel. Clay was dug from the earth, kneaded, coiled, and shaped using simple tools and techniques. Designs were etched onto the surface with sharpened sticks, snail shells, or calabash fragments, creating intricate patterns of lizards, snakes, fish, and geometric motifs. After drying in the sun, the pots were fired in open kilns, producing sturdy, functional vessels used for cooking, water storage, and trade.

This was the world Ladi Kwali was born into. She learned pottery by watching older women, particularly her aunt, and quickly mastered the craft. But while many women in her community made pots as household items or for local trade, Kwali’s work stood out. Her pots were exceptionally well-made, with an artistic quality that made them highly sought after by traders and local elites.

Advertisement

In the palaces of northern rulers, her pots found a place for their utility and beauty. It was through these royal collections that her work first caught the attention of a British colonial officer who would change the course of her life.

MEETING MICHAEL CARDEW

In the 1950s, British potter Michael Cardew arrived in Nigeria as the first pottery officer for the colonial government. He was tasked with modernising pottery production and reviving local crafts. He set up the Abuja Pottery Centre in 1951, bringing European techniques like wheel-throwing, glazing, and high-temperature firing to Nigerian potters.

But when Cardew came across Ladi Kwali’s pots in the home of the Emir of Abuja (now Suleja), he realised something important — traditional Nigerian pottery didn’t need to be “modernised”. It was already remarkable. He tracked her down and invited her to join his pottery centre in 1954.

Advertisement

This was an unusual move. The centre had been dominated by men, and the training focused on Western pottery techniques. Ladi Kwali became the first female potter to join the centre, breaking a long-standing gender barrier. She learned quickly, adapting to the use of the potter’s wheel while still maintaining the freehand techniques of her people. Instead of abandoning her traditional methods, she refined them, combining local and Western styles to create something entirely new.

Her work became a sensation, and soon, her pieces were displayed in exhibitions across the world, from London to Washington, D.C. She toured Europe, demonstrating her craft and teaching others about the rich pottery traditions of Nigeria.

BREAKING BARRIERS IN A MALE-DOMINATED CRAFT

In traditional Nigerian society, pottery was women’s work. But in the professional art world, it was a different story — pottery was taken seriously only when men did it. Kwali shattered that notion.

Advertisement

She was not just the first woman to join Cardew’s training centre; she became its most famous student. She was later appointed as an instructor, mentoring younger potters and proving that indigenous techniques had a place in modern ceramics.

As her reputation grew, she began receiving international honours. In 1963, she was awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) by Queen Elizabeth II. In 1977, she was given an honorary doctorate from Ahmadu Bello University. In 1980, she received the Nigerian National Order of Merit (NNOM), the country’s highest academic award. A year later, in 1981, she was honoured with the national title of Officer of the Order of the Niger. The Abuja Pottery Centre was also renamed the Ladi Kwali Pottery Centre in her honour.

Advertisement

Despite all the global recognition, she remained deeply connected to her roots. She continued to teach, ensuring that younger generations of Nigerian potters, especially women, had the skills to keep the tradition alive.

A LEGACY SET IN CLAY

Advertisement

Ladi Kwali died on August 12, 1984, but her influence never faded. Today, she remains the most celebrated potter in Nigerian history. Her works are housed in museums around the world, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

She is the only woman featured on a Nigerian banknote, appearing on the N20 note.

Advertisement

But her true legacy is not just in money, titles, or museums — it is in the hands of every Nigerian potter who still shapes clay using the methods passed down for generations. It is in the recognition that indigenous art, no matter how humble, can stand alongside the finest works in the world.

As we celebrate Women’s History Month, Ladi Kwali’s story reminds us that history is not just made by those who hold power, write laws, or fight wars. It is also made by those who, with nothing but their hands and their craft, redefine what is possible.

And Ladi Kwali did just that — one pot at a time.

Add a comment