Amidst the biting effects of the coronavirus pandemic that has brought much of the world to its knees, one of the key challenges in Nigeria’s stability, insecurity, has remained unchanged. The country has yet to shake off its tag as the third most terrorised country in the world according to the Global Terrorism Index. In what was a confirmation or an illustration of this reality, a report by Humangle showed that Nigerian lives were up for the highest bidder as 89 people died across the country between Monday, June 29, and Friday, July 3. According to the Council for Foreign Relations’ Nigeria Security Tracker (NST), 55 people were also abducted within the same period.

Violence in Nigeria has taken diverse forms in recent times, as the Islamist insurgency in the North East has remained, so has the Pastoral Conflict between herders and farmers in the North West and across the Middle Belt worsened, and it is happening sporadically in many parts of the South. Added to these are armed robbery, lynchings, gang turf wars as well as a rising rape epidemic. However, the most standout crime in the last decade has been the proliferation of kidnap syndicates across the country, often operating in large forests in the North, and in urban areas in the South.

A report by SBM Intelligence in May showed that between June 2011 and March 2020, no less than $18.3 million was paid as ransom to kidnappers. One thing that stood out is that kidnap for ransom is a thriving industry that looks set to rival gun-running and illegal small arms business in the Sahel. It was this same industry that brought the likes of Chukwudi Onuamadike, also known as Evans the Kidnapper and Hamisu Bala Wadume who was arrested by Nigerian security forces in August 2019. The circumstances surrounding Wadume’s arrest–the death of police officers from the Inspector General’s Intelligence Response Team at the hands of soldiers in the North East, lends credence to the long-held view in some quarters that the Nigerian state and its security services are fuelling instability for pecuniary gains.

Forceful abductions of persons are not just done on land.

Advertisement

The spate of sea piracy in the country’s domestic and international waterways has been spiking in recent times. The Gulf of Guinea is now the most dangerous sea route in the world. In late April, a Panamanian-flagged vessel, Vemahope, a 6,152 DWT product tanker controlled by Piraeus-based Queensway Navigation, was attacked in Nigerian waters and 10 crew members were taken hostage. Security consultants Dryad Global reported that that attack, the seventh deep offshore incident within Nigerian waters this year, brought the number of kidnapped seafarers off West Africa in 2020 to 42. 2020 is on track to follow the piracy highs seen in West Africa last year.

The situation has been no different in the inland waterways of the Niger Delta where Bonny and Degema sea routes in Rivers have become just two of the deadliest sea routes in the region. In mid-February, a container vessel, Maersk Tema while travelling from Pointe Noir, Congo, to Lagos, came under attack at 90 nautical miles, North West Sao Tome. Two unknown men believed to have boarded the vessel and two skiffs were seen in the vicinity of the attack. The vessel drifted for 200 nautical miles, South West of Bonny and 40 nautical miles, South East of the Eastern fringe of the Nigerian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). This incidence bears resemblance to a similar one that happened in Degema, Rivers State, in June, where sea pirates hijacked a passenger boat along the waterways of Namasibi, New Calabar Rivers. The boat was reportedly sailing from Port Harcourt to Ke Clan in Degema when the gunmen attacked it.

Crime-fighting in Nigeria is a seemingly tough subject for a government which oversees a moribund and redundant police force heavily crying for much overdue reforms. Asides being understaffed and underpaid, the problem of lack of resources to check crime has remained countervailing. In recent discussions around the world, the most important culprit in rising police brutality has been the militarization of the police. However, the same cannot be said about Nigeria as many police stations across the country lack basic law enforcement tools. An investigation by the Vanguard in May revealed that a police station in Burutu local government area of Delta state, which serves at least 70 communities in the area, has not a single firearm.

Advertisement

The number of arrests by security agencies, especially the police does not bear any effect on the crime rate. It tells you a few things:

- They reactionarily made mass arrests as they’re wont to do, without credible intelligence, and subsequently arrested the wrong people;

- They deliberately got the wrong people just to show workings due to public criticism;

- They arrested the right people and released them into the population after power must have changed hands.

It must be said that despite these glaring insufficiencies, the police have made some notable, albeit insufficient strides, in combating crime. Although it would (and does) seem like a long stretch, the Nigerian state must actively take steps to reform the Police Force in order to address the challenges it is facing. This commitment must be hinged on the premise that the force has been ineffectual in addressing the numerous insecurities in the country, and this must begin with a comprehensive reformation of the Nigerian Police Act.

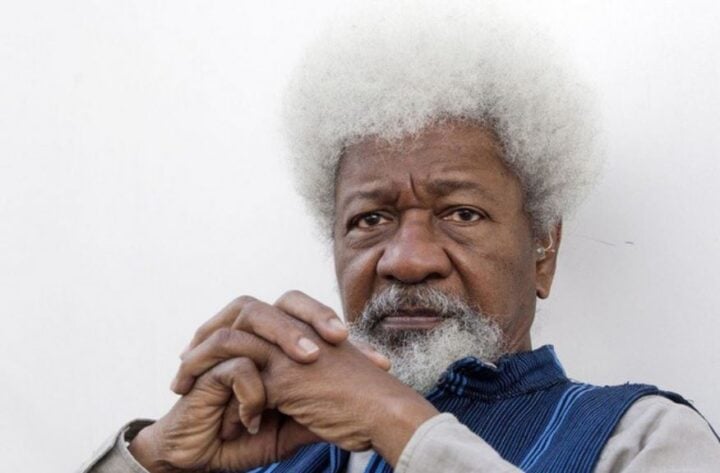

McHarry is a security analyst at SBM Intelligence.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment