BY ANIBE IDAJILI & JENNIFER UGWA

For Daniel Uzor, 34, the first place he heard about the COVID-19 virus was on social media and it was the same place he found out about a vaccine. Admittedly, he was among many who adhered strictly to hygiene and social distancing, but a few months later, when a vaccine was found, he wouldn’t take it because it was produced in the West.

Misinformation from a depopulation agenda to a deliberate lab leak marked the pandemic. Almost every postulation by health experts was second-guessed by millions of social media users reliant on the hot takes of “supposed” health experts and influencers. So, it was not surprising that hesitancy trailed the final manufacture of the vaccine. But some believe this wouldn’t have been an issue if low-income countries (LICs) could and were given patency by top biotechs to reproduce in-country.

“Of course, I would have taken it [if it was produced here]. We love ourselves here,” Daniel told SciDev. The Port Harcourt-based spare parts dealer explained that the unavailability of an in-country-produced vaccine leaves him questioning the efficacy of the serum.

Advertisement

About 13.5 billion doses have been administered worldwide, but only 1.08 billion have been given out in African countries and Nigeria. In the West, booster programmes are already underway, while most persons in Nigeria are yet to receive the first jab.

DISPARITY FUELLING HESITANCY

Advertisement

Nigeria, like most LICs, relies on the financial support of world health institutes to access or afford vaccines. This situation, experts explained, created a messianic position with health interventions in African countries where a small percentage of the monies are allocated to LICs.

In 2021, a collective review, “Addressing power asymmetries in global health: Imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic,” reveals that “much too often, international donors and funding organisations who come as “saviours prefer to fund projects that address their interests”. “Even when research or implementation work is focused entirely on Low or Medium Income Countries, much of donor funds are given to agencies and institutions in HICs, and HICs hold the purse strings.”

A breakdown of the fund allocation shows that “less than 2% of all humanitarian funding goes directly to local NGOs. About 80% of USAID’s contracts and grants go directly to US firms. Moreover, 70% of NIH Fogarty grants go to the United States and HIC institutions, and 73% of the total international grant portfolio of the Wellcome Trust supports United Kingdom-based activity,” it revealed.

The review also highlighted, “Even when funds are given to LMIC agencies, HIC donors often set the agenda and micromanage the work, leaving little room for LMIC groups to innovate.”

Advertisement

“The COVID-19 pandemic stimulated us as scientists [in Nigeria] to look into products and therapeutic vaccines and see how we can develop them in-country,” said Tobin Ekeatte, consultant and public health physician at the Institute of viral hemorrhagic fevers and emerging pathogens.

“Especially when we had challenges getting them from the high-income countries, not only because we didn’t have the money to buy the vaccines, but because they would prefer to give those vaccines to their people first.”

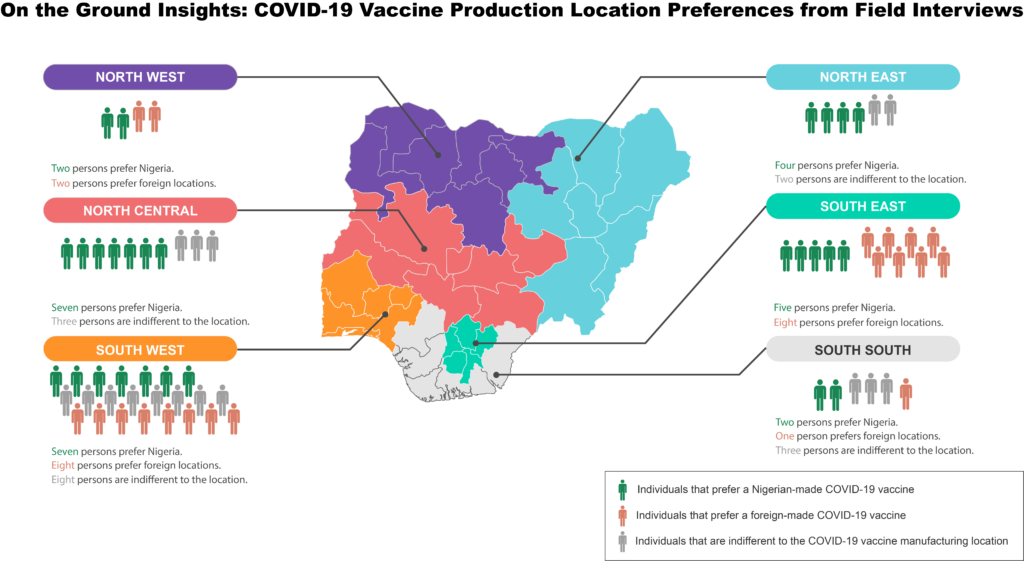

Immunisation officers that journalists spoke to said vaccine production in Nigeria would improve uptake and build citizen trust in the jab.

“Sometimes, they will say the vaccine is unavailable and is now available in another minute. Other times, we don’t have enough vaccines,” said Zainab Adamu, immunisation officer at Suleja Teaching Hospital, Niger state.

Advertisement

The report reveals that plans for African countries to self-produce the COVID-19 vaccine were thwarted by top biotech companies, who defined these moves as “not favourable”.

Advertisement

Financial involvement involved in vaccine production, health experts like Ekaetta and Sule Samson, a medical doctor at the Federal Medical Center Lokoja, agreed is huge, but Sule explained that issues like supply monopolies by HCIs contribute to the hesitancy.

“The reason why I haven’t collected the second dose of the vaccine is because I don’t trust the source,” said Yusuf Abdullahi Abubakar. Yusuf, who works as a janitor, took the first dose after he lost a neighbour to the virus. “If these vaccines are produced in Nigeria, I will make myself available for the second dose.”

Advertisement

Kenneth Nnaji, a public health expert, said it would be difficult to convince an average Nigerian who understands the impact of fake or counterfeit drugs to accept a vaccine trailed by so much controversy when it is found that one in ten medical products in low-income countries is either substandard or falsified.

“I won’t call it fear, but I will say reservations,” said Amaka Otuosorochi, a Port-Harcourt-based petty trader. “Like in my line of business, suppliers ship inferior products to Nigeria because they feel it’s okay to send them to us. So I just feel that’s the case with the vaccine.”

Advertisement

Experts say misinformation on the COVID-19 vaccine could affect the uptake of other vaccines. Nigeria plans to commence the first roll-out of the human papillomavirus vaccine, but research shows that a good number of the target population (women) are open to testing and not the vaccines.

Experts said this is linked to fake news of sterilisation during the pandemic. An example is Amina Ahmad, 40, in Kano state, a vaccine-controversial region in Nigeria is one of the women who told journalists that although she has no plans of giving birth to a daughter said she will not take the jab. Her fear stems from unfounded rumours of forced sterilisation.

However, this may have the same effect across the board, especially “not in an area where a virus is endemic, like in the Lassa fever case. People already understand they need the vaccines,” said Ekaetta, who is part of the vaccine trial team.

THE COST OF SAVING A NATION

The COVID-19 shots were developed at record speed, just over a year after a mysterious pneumonia surfaced in China. And not everyone is perturbed by the vaccine producers.

After Omotola Adeniyi’s cousin’s demise in June 2022 from the coronavirus, she made plans to take the first shot without her husband’s—not a big fan of Western medicine—knowledge. Also, Jehu Alozie, a ground manager at a brewery in Enugu, received the vaccine despite his wife’s aversion. “In fact, that the vaccine was not produced in Nigeria made me trust it,” he said.

If Nigeria produces its vaccines, it would cost much more than the N10 billion (about US$26 million) released in 2021 to support the domestic production of COVID-19 vaccines. In the same year, the United States government spent between $18 billion and $23 billion on vaccine development and production.

Official reports from the Ministry of Health in 2021 claimed Nigeria was exploring options for licensed production of COVID-19 vaccines in partnership with recognised institutions and had even begun talks with a local producer. However, nearly three years after this remark, the only laboratory for manufacturing human vaccines in the country has remained shut since 1991.

Within the last three years, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research have received only N10.5 billion and N9.3 billion, respectively, in budget appropriations. Only N7.6 million has been allocated for a biotechnology approach to combating COVID-19.

In 2022, N1.25bn was awarded to four clusters of researchers under the Vaccine Development Mega Research Project to develop the COVID-19 DNA Vaccine Candidate (SJN3T CorVac) for preclinical trials in 2023.

By 2028, Nigeria will no longer be eligible for the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) funding. With an exploding population growth at approximately 2.4% annually and a low Gross Domestic Product of 2.51% (year-on-year), the country may come to rely heavily on external private resources from international philanthropists as internally generated tax remittance will not fund an in-country vaccine production plan compared to HICs like the US where hundreds of billions of dollars are appropriated to the Biomedical Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to develop the scientific infrastructure to produce vaccines.

While a good population has received the vaccine and many more are seeking out the jab themselves, “I think it’s high time the black man produced his vaccines,” said Rose Matugi, the vaccination officer in Jalingo, Taraba state.

Jennifer and Anibe are 2022 Public Reference Bureau Public Health Reporting Corps fellows.

Add a comment