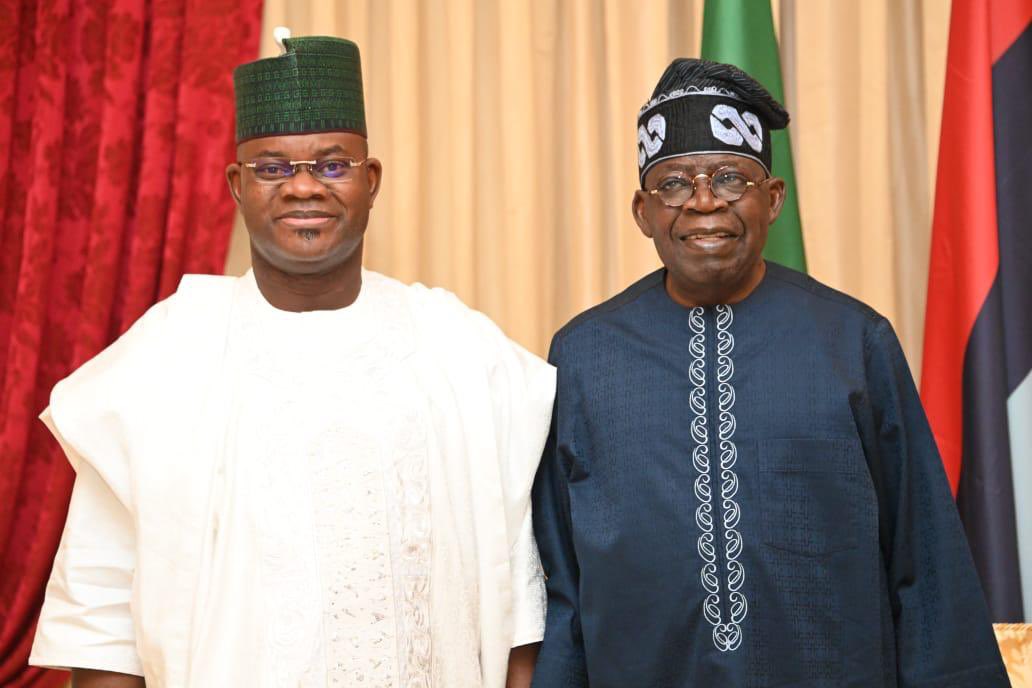

Yahaya Bello

Native Brazilians arrest monkeys with what is called Cumbuca. They make a hole in a gourd that is big enough to accommodate the hand of a monkey. The gourd is then affixed to the ground of the place monkeys infest. Placed inside the gourd is usually a banana to attract the monkey. The monkey then hops down the tree and aims to grab the banana. Expectedly, the monkey will foolishly hold on tight to the banana, his hand closed. With this, the monkey cannot take the banana out and will not leave his place of imprisonment. He will be there until he is made into a delectable barbecue. I will relate this presently.

Habeeb Okikiola, a.k.a. Portable, the weird head housing a huge cerebrum, proposed a thesis which I want us to examine together. In a viral video, Portable pleaded with the EFCC not to get him arrested. In the last three weeks or so, the EFCC has upped its proficiency in arresting those it labelled mutilators of the Nigerian currency. Last week, Pascal Okechukwu, a famous socialite, popularly known as Cubana Chief Priest, got his full comeuppance. He was arrested by the EFCC and dragged before a Lagos Federal High Court which granted him a bail of N10 million.

Before then, in January, Nigerians were treated to the salacious broth prepared by Betta Edu. Edu is the suspended Minister of Humanitarian Affairs and Poverty Alleviation. The 37-year-old Edu had been enmeshed in allegations of fraud involving the sum of N585.189 million. As we speak, Betta and her accomplices walk the streets free. There are strong allegations that the Edu you see is a butterfly, a mere façade covering a roiling colony of maggots in the Nigerian presidency. And that the EFCC’s dilemma in not replicating the clinical accuracy and Concorde-speed conviction it attained with Bobrisky in Edu, can be likened to a chemistry which the Yoruba forged between the shrub and the forest. It is their simple law of gravity, their Archimedes Principle if you like. So, they say, if you pull too hard on the shrub, it will pull the forest (Ti a ba fa gburu, gburu a fa’gbo). And trees will fall over trees.

A line from Sudanese novelist, Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North also interests me. Salih’s is a classic postcolonial Arabic novel published in 1966. The line is, “I am no Othello, Othello was a lie…I am a lie.” The book revolves around a man called the “travelled man,” an African who just returned from schooling abroad in the 1950s. He came back to his Sudanese village of Wad Hamid, located on the Nile. He had just finished writing his doctoral thesis themed ‘The Life of an obscure English poet.’ I found this ‘lie’ line the most profound of Salih’s conversations. What gave life to that conversation? When he arrives home, the unnamed narrator meets a villager named Musrafa Sa’eed, the main protagonist of the novel. Sa’eed is described as “a monstrous product of his time.” One drunken evening, the narrator encounters Sa’eed in his real self. So he asked him about his past. Sa’eed gave that curt reply of “I am a lie”.

Advertisement

“I am a lie” is almost synonymous with the life of a butterfly which my people call the “labalaba.” The butterfly is Janus, the double-faced god. When you think it is attempting to perch, that is when the poor fly is on the verge of taking off. In painting an ample picture of the ephemeral nature of the butterfly, my people conjured an incantation to explain its fleeting life. “Yio ba’le, yio ba’le ni labalaba fi nwo’gbo” they say. The life of labalaba is like a joke. A lie.

Like Sa’eed, Nigeria’s season of migration to the double life of a butterfly – the season of lies – seems to have come. Such seasons come and go like the ever-changing colours of a chameleon and unfold like the rainbow. Beginning with the drama of power in Abuja last week which involved ex-Kogi state governor, Yahaya Bello and the Nigerian state; the clowns in Ibadan who attempted to take over the Nigerian state; to the EFCC’s most recent tickling fancy in arresting “currency mutilators”, Nigeria has entered a full plumule of its season of migration to lies.

Last Friday in Ibadan, I sat beside the former Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academics) of the University of Ibadan, Prof Adigun Agbaje. It was at a reading and review session of Cyber Politics, a book authored by Omoniyi Ibietan, a man trying to cultivate a forest of a thousand – and one – grey hairs that could rival Wole Soyinka’s! And Agbaje propounded a thesis which seems to explain some of the labalaba stories that erupted in Nigeria in the last week. He began by asserting that the politics of meaning is changing rapidly, not only in Nigeria but all over the world. In other words, the meanings we ascribe to political issues are fast changing their frontiers.

Advertisement

The politics of meaning was put in context by Michael Lerner in his 1997-published book, The Politics of Meaning: Restoring Hope and Possibility In An Age Of Cynicism. Lerner drew on ideas presented in the Bible, Jewish teachings, and his experience as a psychotherapist to examine the roots of discontent of many Americans about their political system. He also describes how values get lost in broken politics. Agbaje took on Max Weber’s classical definition of the state. The German sociologist had submitted, in what is widely regarded as a defining characteristic of the modern state, that the state alone has a monopoly on violence. In political science and sociology, Weber’s definition of the state has influenced several theses of the state being the only one in possession of the right to authorise the use of physical force.

In what appears very elementary reading of Lerner and Werber, Portable, last week, explained the shifting sand of meaning and the power of the state. While begging EFCC not to arrest him, the weird musician had said, “After God, na government; forgive me if you have videos of me spraying money.” The EFCC has over the years indeed shifted in meaning. Whenever he was to be vilified, opponents to the politics of Nigeria’s first president, Nnamdi Azikiwe, a.k.a. Zik, mocked him as having fallen from an Olympian height of Zik of Africa to Owelle of Onitsha. In 2003 when President Olusegun Obasanjo established the EFCC, criminal elements among the political class, like roaches at the sight of a hen, scampered for safety. The fate of the ones caught by the dragnet of the then no-smiling Nuhu Ribadu was akin to that of a man who carries a faggot laden with a thousand bees – “o ru’gi oyin!”. Inspector General of Police, Tafa Balogun, became jelly when rounded up by Ribadu boys.

Ribadu’s adulterous romance with politicians can be explained. One by one, he unwittingly renounced all his lofty crime-fighting credentials. Today, Ribadu sits at the table with the same persons who dreaded his dragnet and takes orders from a man he almost hounded into jail. The lion is castrated and the sons of impala tug at the King of the Jungle’s naked “blokos”. From running after Yahoo Yahoo boys on university campuses to pursuing social nuisances who defile the Naira, the EFCC’s season of shifting meaning, a migration to hubris, has come full throttle. I think the assignment given to the anti-graft agency by the law is too monstrous for this fleeting role it casts for itself.

Gradually, the EFCC was struck by the nuke of a shifting politics of meaning. Ribadu himself became the proverbial fetus inside a cobra that kills the snake. I remember the saying that, the moment you thrust your hand forth for a handshake, your head will bow. Yoruba stretch this saying further, exploiting the alliteration in plantain – dodo – and truth, ododo – to say that the moment you eat the dodo, you can no longer be found in the comfort of ododo. Ribadu’s head became bowed the moment he coveted the sweet pancake in the hands of the political class. It was the case of the squirrel comfortably seated on a deathly trap to enjoy a dinner of bananas that he loves so much. How was the squirrel to know that sweet things are most times expressway to death? Politicians seem to have discovered the EFCC’s price tag. So, Ribadu joined politics. The moment he did this, he got for himself a belt made of “yangan”– corns, which became his waistband. By so doing, the well-respected ex-cop became a fawning piece (alawada) for hens to play with. He also becomes the monkey that native Brazilians arrest with the Cumbuca.

Advertisement

Then came the melodrama starring ex-Governor Bello and the EFCC. Last week, after obtaining a court warrant for his arrest on the allegation of an N82 billion fraud, viral videos showed the commission’s futile efforts to arrest Bello at his Wuse Zone 4, Abuja home. The world watched the circus of our national shame. When Bello-installed incumbent governor of the state, Usman Ododo, made a serpentine sneak into his godfather’s Abuja house in his official convoy and allegedly whisked Bello away, the world was aghast. Rather than provoke laughter, the circus induced hot streams of tears. The EFCC has since declared the former governor wanted.

In the Kogi melodrama, you will find jutting out the same labalaba story. It describes the politics of meaning and how Weber’s definition of the modern state has suffered some shifts. With the helplessness that the EFCC showed in bringing Yahaya Bello to book, does the Nigerian state still possess the monopoly of violence? Where is the state? Where is the violence? What can explain an alleged felon outwitting the full complement of the arsenal of the state,? The only explanation I can readily find is in science. In a human-animal relationship, (HAR) scientists found out that when you domesticate even a dreadful animal like the lion, a familiarity creeps in. Yahaya Bello must have fully understood this symbiosis between the political class and the anti-graft agency and was hell-bent on exploiting it. So, he called on his lickspittle, Ododo, to come to denigrate the power of violence of the Nigerian state. The EFCC looked on, helpless.

Now, a set of people whom ex-Lagos Commissioner of Police, Fatai Owoseni, aptly described as high on cheap drugs, attempted to take over the Oyo state government last Saturday. It was another low layer in the confrontation against the Nigerian state. While Weber talked about the awesome omnipotence of the modern state, which Portable’s “after God, na government” statement corroborates, there is massive resistance against the state in Nigeria. It is almost useless in the lives of the people. It is perceived as aloof, unrepresentative, effete, distant and which only flexes its muscles against people at the lowest rung of the ladder. When it comes to the exhibition of raw brunt, the Nigerian state is in a hyper mode.

Take, for instance, the Gestapo-like arrest and detention for 14 days of FirstNews editor, Segun Olatunji. He was clamped in a dark-tunnel military detention reminiscent of Col Frank Omenka’s Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) during the Sani Abacha years. In a supposed democratic government! Omenka was Abacha’s Director of Military Intelligence who inflicted gruesome mental and physical torture on journalists and pro-democracy activists. Olatunji claimed his arrest was in connection with a story written by his medium on alleged shady deals in the Tinubu presidency. He also alleged that his detention was at the behest of Tinubu’s mis-chief of serfs. As we speak, the government of Tinubu who came to the democratic platform due to his recognition as a fighter for the rights of the people, has said nothing about Olatunji’s detention.

Advertisement

People tend to locate the silence from the Villa in that profound allegory of obligations put together by the Yoruba. You can liken it to what lawyers call the responsibilities of the delegatee, delegator and obligor. Yoruba tell it as an allegory. There was once an assembly of some poisonous and powerful reptiles. The cobra – Oka – was cooking the broth for all to eat; the python (Ojola) was washing the dishes where the food would be served. When Scorpion, the Akeeke, was sent on an errand and he began to worry that he could be stung by a poisonous animal on the road, Yoruba wondered whether a shield greater than the python and cobra existed anywhere for the scorpion. (“Oka nda’na, Ere nfo awo; won ni ki akeeke lo ra nkan wa l’oja, o ni kinikan a ta ohun”). Who dares light a lamp to look at the face of a leopard? In law, it is represented as three parties who are concerned with an act. The three of them form a whole. It can be likened to the impression out here that, in this Omenka-lization of the Nigerian presidency, the mis-chief of serfs has the full backing of the lord of the Villa.

Postscript: Last week, a close ally of Chief Olabode George called to make representations on my piece, The Lagos Boy’s Coastal Highway. He stated as follows: George was Military Governor of Ondo State for four years and not the two years I stated. Yes, an African Concord magazine report accused his regime of presenting refurbished canoes as new but it was part of a gang-up against George by those who couldn’t stand him. Chief MKO Abiola’s personal intervention halted actions George was prepared to take against the magazine. The slap story between Mrs George and the then Ondo State Permanent Secretary never took place. It was part of undying concoctions to disparage the Georges. Mrs. Feyi George was an urbane character, from a very respected family, who helped the cause of women as First Lady. She was responsible for bringing women into the military cabinet of Bode George. She was far from being the arrogant and garrulous character painted in recordings of her time as Ondo’s First Lady, said the Chief George ally.

Advertisement

Tolu: The Nigerian who won a game of greed

When a few Nigerians bring disrepute the way of Nigeria abroad, some others uplift it. Tolu, daughter of Grace and Gbenga Ekundare, is in the latter category. Born in 1996, Tolu is an American celebrity in the entertainment industry accorded for her brain and passion. She was one of the cast of Netflix’s The Trust: A Game of Greed. In this game, total strangers to one another are handed $250,000 to divide among themselves. Miss Ekundare, a Houston-based model and marketing manager, whose father hails from Ilesa in Osun state, strategised in that reality competition to take out the first player. While doing this, she exhibited the consistency that is the hallmark of a Nigerian and left the show as one of the five winners, going home with the sum of $73,600 as the winner of the second-largest prize out of the group.

Advertisement

When the Nigerian Channels television interviewed Ekundare a few months back, she evidenced a spirit that borders cannot limit. The reality show didn’t go without her encountering that undying ghost of race in America. She confronted a huge pall of tokenisation and racism which every Black person doing the exemplary encounters in America. A memorable scene in the show exemplifies what she went through. It was a tear-provoking conversation between Jake and Ekundare. Perhaps egged on by the Osomaalo spirit of industry and resistance that is said to be genetically woven into the constitution of every Ijesa, she did not hide how uncomfortable she was at being typecast as the “African queen sister” of the house.

“I think I did amazing, especially considering how even with the whole house gone, I clawed my way out of the corner,” Ekundare told a magazine, Vulture. “I think my gameplay was on point. It was just who I was aligned with that was the issue.” Asked about the financials of the win, Ekundare said, “I can’t speak for everyone else, but the premise was so crystal clear to me, Winnie, and Julie. Mind you, $250,000 … if it was one person, that’s a life-changing amount of money. But divided by 11, pre-tax, we are at $22,000 [each], and then Uncle Sam will take his cut. I can’t even buy me a little Toyota Corolla with that.”

Advertisement

Congratulations to Tolu, daughter of my childhood friend, Gbenga, with whom, in the company of our late friend, Adeyoju Peter Aiku, I walked the length and breadth of Ilesa, Osun state in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment